Purdue University research into scattered kaolinite rocks on Mars’ surface shows the dry, dusty planet could have featured a rain-heavy climate billions of years ago. Credit: NASA

Purdue University research into scattered kaolinite rocks on Mars’ surface shows the dry, dusty planet could have featured a rain-heavy climate billions of years ago. Credit: NASA

Forget the dusty, rusty landscape you see today. Billions of years ago, Mars may have been soaking wet. Tropical storms might have drenched the Red Planet. That is the startling conclusion from new fragments of clay found by NASA’s Perseverance rover in the vast Jezero crater.

The rover found thousands of light-toned rock fragments, or float rocks, scattered across its mission path. These fragments, ranging in size from pebbles to boulders, stood out against the reddish-orange Martian surface. Chemical analysis revealed they are composed of aluminum-rich kaolinite clay. For those of you who aren’t geologists, kaolinite is a powerful indicator of a past soaked in water.

Fragments of a Watery Past

On Earth, this white clay requires an almost unbelievable amount of liquid water to form. It takes millions of years of rain and wet weather to leach out all the other minerals from the original rock and sediment. This process is most common in Earth’s tropical climates and rainforests.

For the same clay to appear on Mars, a planet now “barren, cold and with certainly no liquid water at the surface,” means “there was once a lot more water than there is today,” explained Adrian Broz, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral collaborator on the Perseverance rover mission.

These clay fragments, scattered like misplaced relics, point toward a Martian past that feels almost disorienting to imagine: long-lived rainfall, humid air, and soil chemistry usually found in Earth’s tropical regions. It’s a world where the Red Planet wasn’t red at all, but wet, warm, and teeming with chemical reactions that may have been conducive to life. The data suggests ancient Mars’ weather had a mean annual precipitation greater than 1000 mm.

“They’re clearly recording an incredible water event,” Briony Horgan of Purdue University said, referring to the kaolinite. “But where did they come from?”

That’s indeed the million-dollar question that has planetary scientists buzzing.

Rocks Shaped by Rain on Mars

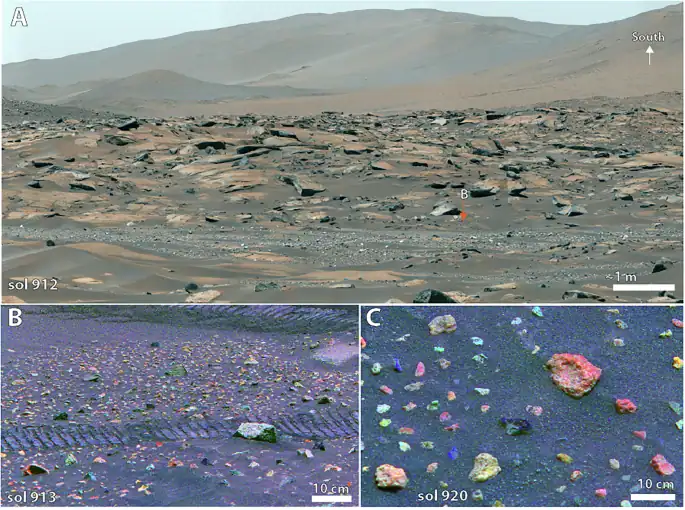

Mastcam-Z landscape and multispectral images of light-toned float rocks atop the Jezero crater Margin Unit near the Hans Amundson Memorial workspace (Sol 912) demonstrating the spectral diversity of this material. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

Mastcam-Z landscape and multispectral images of light-toned float rocks atop the Jezero crater Margin Unit near the Hans Amundson Memorial workspace (Sol 912) demonstrating the spectral diversity of this material. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

For decades, scientists have known that Mars once had water. They’ve found river channels and ancient lakebeds. But rain — persistent, long-term precipitation — has always been harder to prove. Kaolinite changes that.

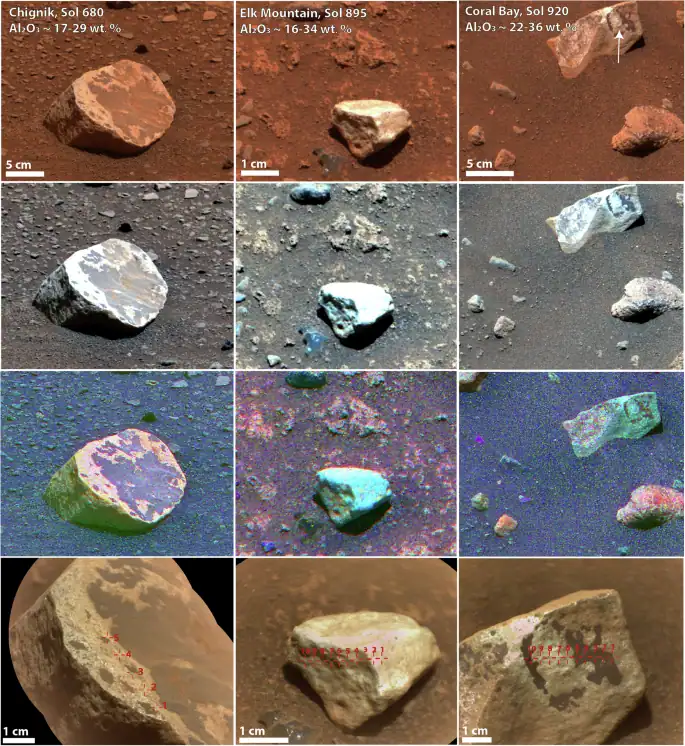

SuperCam and Mastcam-Z instruments on Perseverance recorded aluminum-rich kaolinite spectral fingerprints. The team compared the Martian samples to several Earth analogs: deeply weathered paleosols from coastal Southern California, ancient 2.2-billion-year-old paleosols from South Africa, and hydrothermal kaolin deposits spanning Iran, Malaysia, and Argentina.

The chemistry was unmistakable. The stones contained 30 to 45 percent aluminum oxide, extremely low levels of iron and magnesium, and a distinct spectral signature of kaolinite. On Earth, that pattern appears only after rocks have been leached clean by millions of years of rainfall under warm, humid conditions.

“These could be evidence of an ancient warmer and wetter climate where there was rain falling for millions of years,” Horgan said.

Mastcam-Z and SuperCam observations of the “hydrated class”1 of aluminum (Al)-rich float rocks at Jezero Crater, Mars. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

Mastcam-Z and SuperCam observations of the “hydrated class”1 of aluminum (Al)-rich float rocks at Jezero Crater, Mars. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

The Martian rocks matched Earth’s deeply weathered soils almost perfectly. They were nothing like kaolin deposits formed by hydrothermal systems, which occur when hot underground water alters rock.

Yet the pale stones are scattered far from any visible source. Perseverance has seen no nearby outcrop that could explain the fragments littering the crater floor.

Where Are They From?

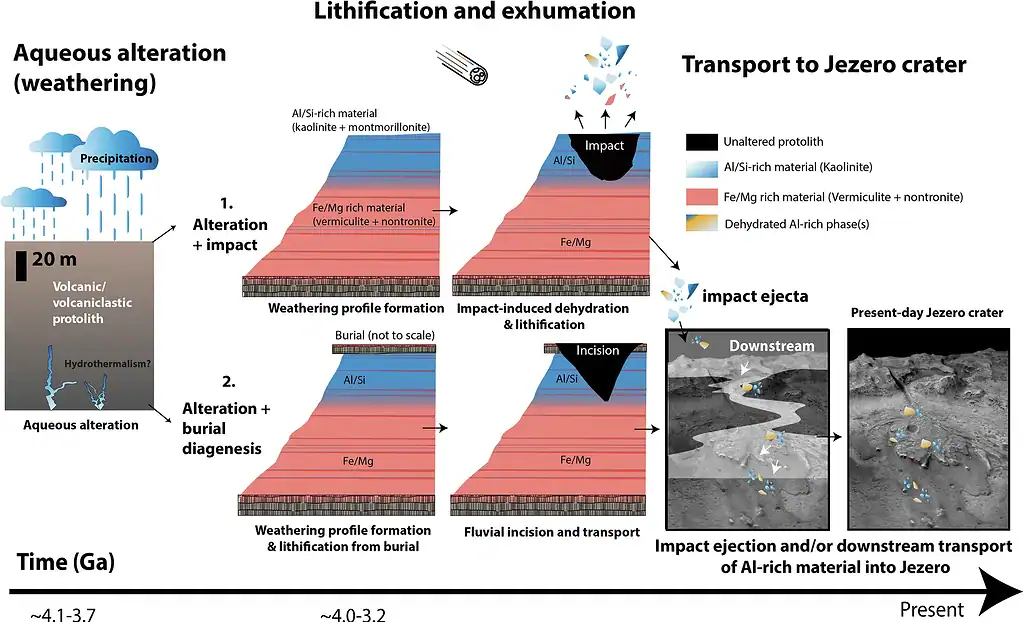

Proposed sequence of events for Al-rich float rocks at Jezero Crater. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

Proposed sequence of events for Al-rich float rocks at Jezero Crater. Credit: Communications Earth & Environment, 2025.

Jezero crater once held a lake twice the size of Lake Tahoe, and scientists think the light-toned rocks could have been carried there by rivers flowing into the basin. Another possibility is that they were blasted into the crater by impacts that threw debris across the landscape. Orbital images show larger patches of kaolinite-rich rock on the crater’s rim and along the channels feeding into it. But until Perseverance can climb to those outcrops, the origin of these pale boulders remains unsolved.

Whatever their journey, their presence hints at a planet that once had not just lakes, but a full hydrological cycle: a sky that could fill with moisture, clouds that could burst, and soils that could weather under ceaseless rain.

“All life uses water,” Broz said. “So when we think about the possibility of these rocks on Mars representing a rainfall-driven environment, that is a really incredible, habitable place where life could have thrived if it were ever on Mars.”

A planet that dried itself out?

The researchers believe the formation of these aluminum-rich clays may have helped turn Mars into the dry desert it is today. When kaolinite forms, it traps water molecules inside its crystal structure. On Earth, plate tectonics recycles that mineral-bound water back into the atmosphere through volcanism. Mars, with no tectonic activity, had no such escape route. The water that once soaked the planet’s surface may now be locked in these minerals forever.

As the study notes, “the presence of kaolin-group minerals … implies large quantities of liquid water once participated in intense chemical alteration.” Over time, that chemical process may have permanently pulled water out of the Martian atmosphere. The same rainfall that once made Mars habitable could have started its long desiccation.

For Horgan, Broz, and their colleagues, these findings represent the wettest (and possibly most habitable) interval yet documented on Mars. The data suggest sustained precipitation, not a single climatic outburst. “Elsewhere on Mars, rocks like these are probably some of the most important outcrops we’ve seen from orbit because they are just so hard to form,” Horgan said.

If confirmed, it would mean that parts of Mars once looked less like Antarctica and more like the Amazon Basin. The ultimate goal, of course, is to find out if the ancient rainfall that created these tropical conditions also nurtured life. With the rover poised to explore more terrain and potentially track down the missing outcrop, the dream of Mars as a former wet oasis is becoming a verifiable scientific fact.

The findings appeared in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.