When a magnitude 8.8 earthquake ruptured off the coast of Russia this summer, it triggered a Pacific-wide tsunami, causing waves to arrive as far away as Hawaii.

The quake was so powerful that sea lions were seen fleeing into the ocean and surgeons struggled to hang onto a patient during an operation.

It was the sixth largest earthquake in recorded history.

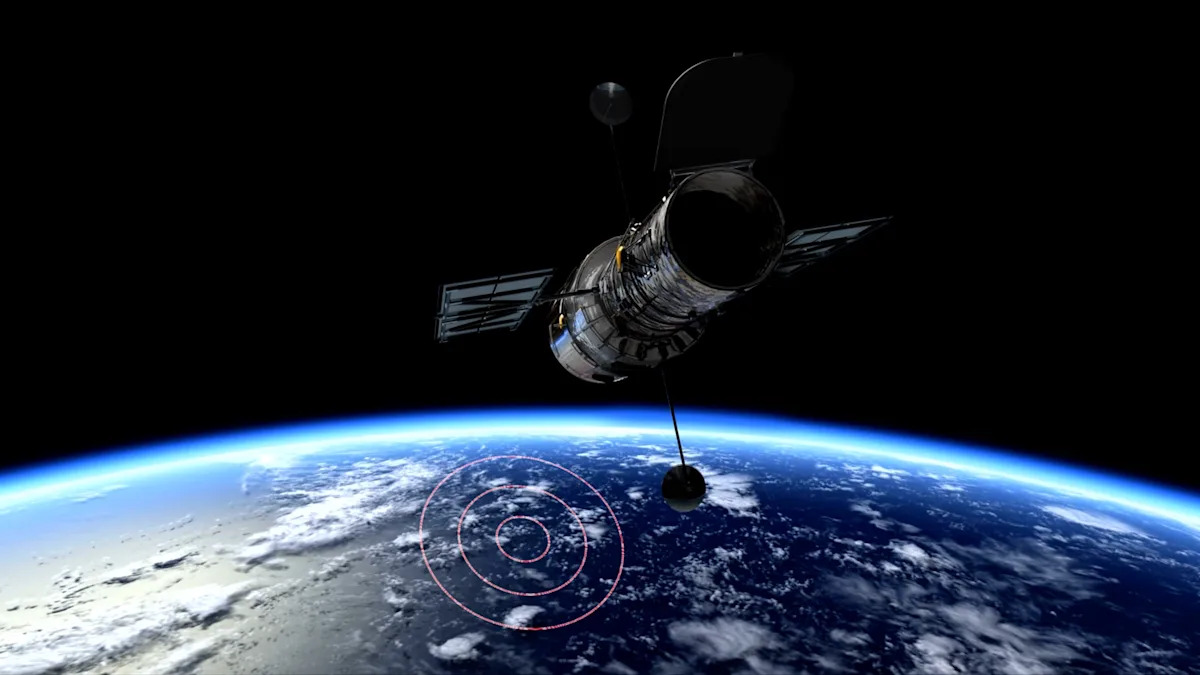

And there was a satellite looking down from above on everything as it happened.

The new Surface Water Ocean Topography measured the entire event, capturing the first high-resolution spaceborne track of a great subduction zone tsunami.

The specialized satellite was designed to track ocean water by measuring changes in surface height.

Researcher Angel Ruiz-Angulo at the University of Iceland said in a recent interview, “I think of SWOT data as a new pair of glasses. Before, with DARTs we could only see the tsunami at specific points in the vastness of the ocean. There have been other satellites before, but they only see a thin line across a tsunami in the best-case scenario. Now, with SWOT, we can capture a swath up to about 120 kilometers wide, with unprecedented high-resolution data of the sea surface.”

While the massive tsunami this summer was, in the end, relatively harmless, the insights gathered from the SWOT satellite and Ruiz-Angulo’s report could help protect coastal communities in the future.

While tsunami warnings are already in place based on predictive models, the satellite data was detailed enough to show inaccuracies in those expectations.

Ruiz-Angulo and his colleagues used that data for a landmark report on “hazard implications of short recurrence intervals of great earthquakes and show how rupture style governs tsunami severity.”

The team expects to keep using the satellite to track tsunamis in the future.