Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

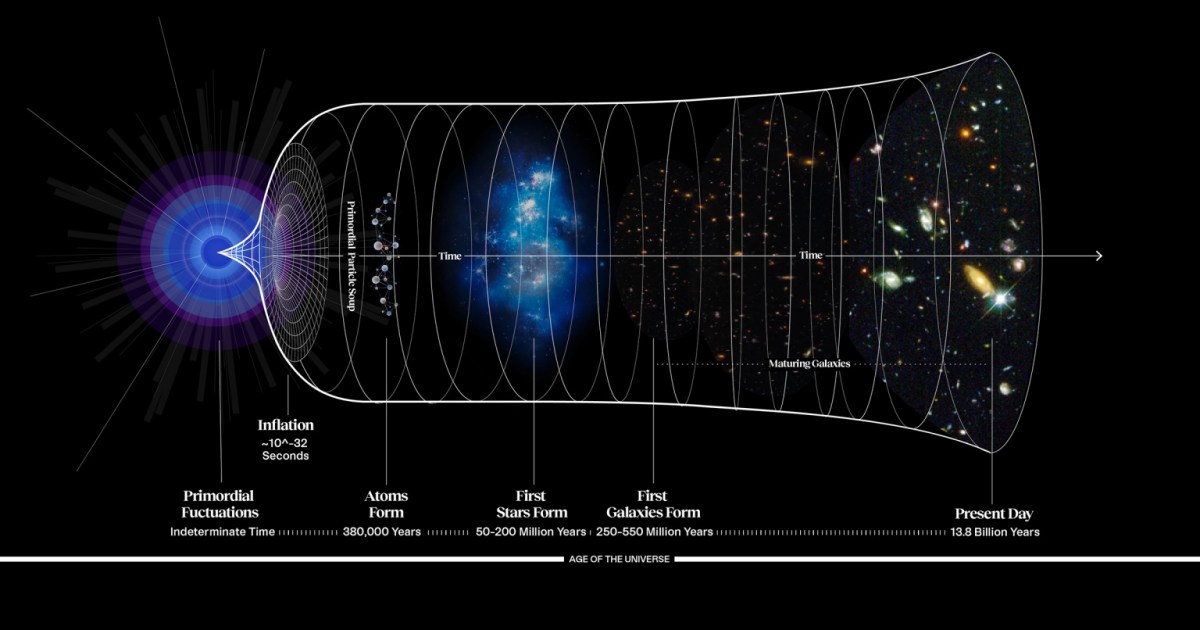

Every year, scientists around the world don’t just work to enhance what we know and increase our overall body of knowledge, although that’s indeed what they wind up doing. Part of the motivation for conducting science is hope: the hope that what you’re doing, research-wise, could end up revolutionizing how we conceptualize reality. Although we’ve come so far in understanding this Universe — including what its laws and constituents are at a fundamental level, and how those fundamental components assemble to create the varied and complex reality we inhabit today — we’re certain that there’s still more to learn, as many paradoxes about and several important puzzles remain unsolved. With each new experiment, observation, and piece of data, there’s an opportunity for scientific advancement.

All too often, however, for better or for worse, what initially seemed like:

- a mismatch between theory and observation,

- a low-significance hint that, if confirmed, would contradict our consensus picture,

- or a set of observations that supported a non-standard framework for the Universe,

appears to crumble or disappear as new, superior, and more comprehensive data was collected. Although there are always a series of sensationalistic science headlines that come out in any given year, the sober reality is that there are a great many scientific truths that continue to persist, despite their unpopularity among non-scientists, because the full suite of data ovewhelmingly supports them.

In the case of the Universe, our “Standard Model” of both particle physics and cosmology remains as our consensus framework and foundation: the starting point for all the scientific endeavors we conduct today. Despite all the claims to the contrary, the Standard Model still hasn’t cracked. Here’s why.

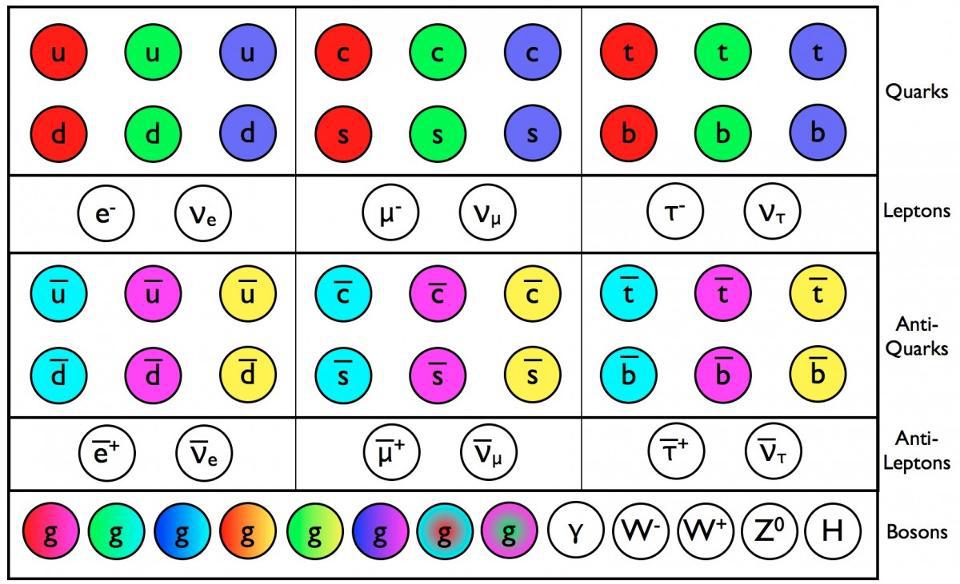

The quarks, antiquarks, and gluons of the Standard Model have a color charge, in addition to all the other properties like mass and electric charge. All of these particles, except gluons and photons, experience the weak interaction. Only the gluons and photons are massless; everyone else, even the neutrinos, have a non-zero rest mass.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

What you see, above, is an illustration of the Standard Model of elementary particles. Its ingredients include:

- the six quarks, each of which come in three different colors,

- and the six antiquarks, which come in three anti-colors,

- the charged leptons, the electron, muon, and tau, plus their antimatter counterparts,

- the three types of neutrino, the electron, muon, and tau, plus their antineutrino counterparts,

- the force-carrying particles: the single photon, the three heavy weak W-and-Z bosons, and the eight gluons,

- as well as the (lone) Higgs boson,

which interact through the electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear forces, as well as through gravity. At high energies, the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces unify into the electroweak force.

This framework doesn’t explain everything, however. Mysteries include the origin and nature of dark matter, the nature of dark energy, the existence of more matter than antimatter (the baryogenesis puzzle), and the hierarchy problem: the lack of a mechanism for explaining the values of the rest masses of each of these particles. Going into the year, there were a variety of questions surrounding the Standard Model, and whether it would hold or be challenged by new data by the end of the year.

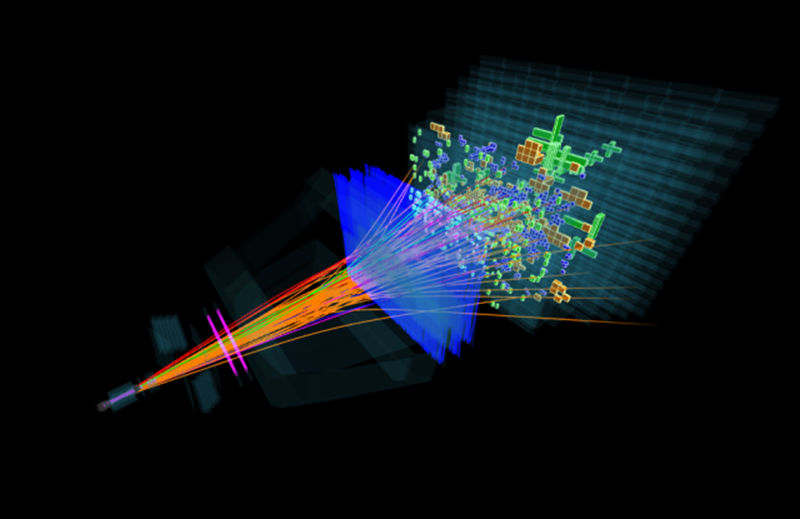

This 2016 reconstruction of an LHCb event shows a b-quark containing baryon that decayed, producing an s-quark containing baryon along with other mesons. With observations of sufficient numbers of these decays, the LHCb collaboration, in 2025, was able to show evidence for baryonic CP violation for the first time.

Credit: CERN/LHCb collaboration

For example, we knew that CP-violation, or a difference in the behavior of matter from antimatter when you take the mirror-image counterpart of one or the other, occurs in nature: it’s been exhibited by strange, charm, and bottom quarks in a variety of mesons. But would CP-violation, a necessary ingredient to explain baryogenesis, also appear in baryons of any type? In 2025, physicists working as part of the LHCb collaboration demonstrated that indeed, yes, baryonic CP-violation is real, finding evidence for it in the decays of two b-quark containing baryons. A potential challenge to the Standard Model rose and fell, demonstrating no need for physics beyond the Standard Model to explain the behavior of these particles.

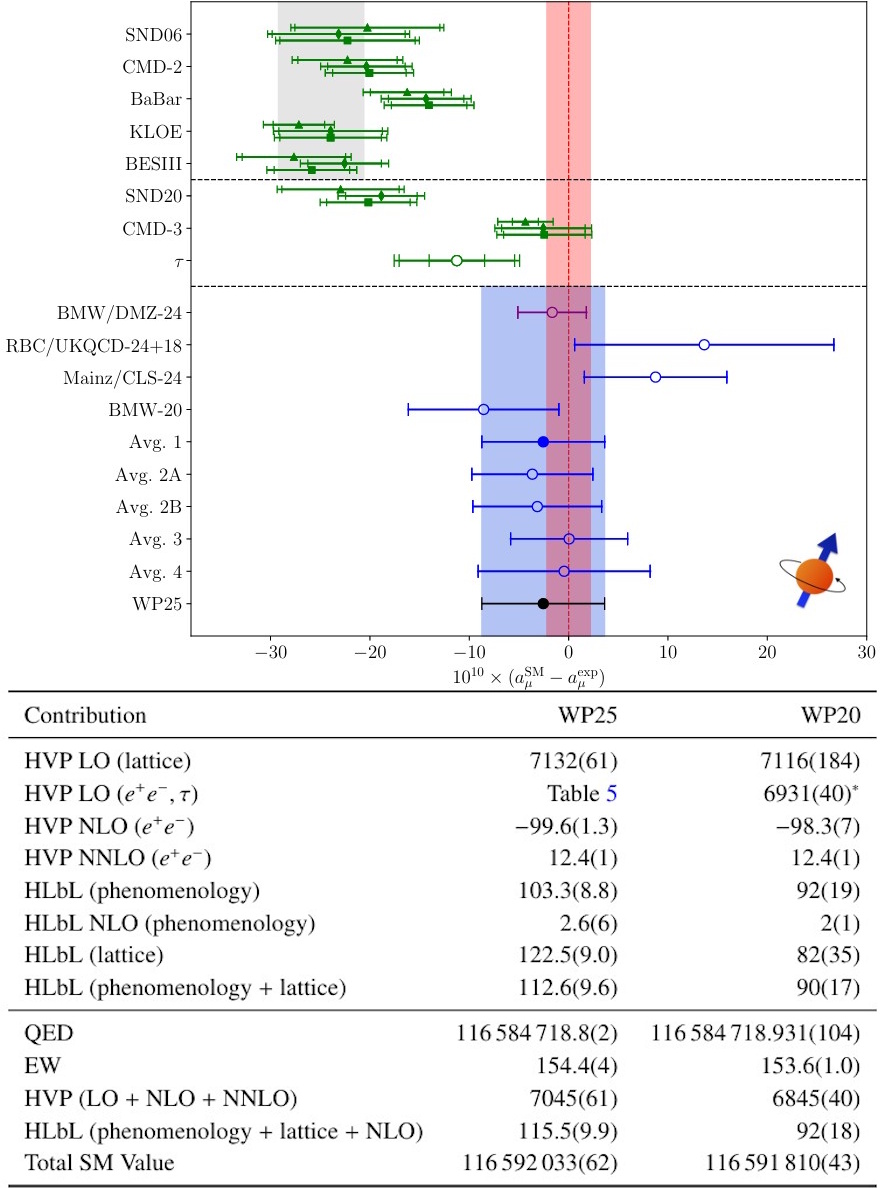

For many years, it appeared that there was an anomaly in the magnetic moment of the muon, and that an enhanced experiment at Fermilab, the muon g – 2 experiment, would finally get us to the necessary significance to see a difference between theory and experiment. Although the experiment did indeed reach the desired precision, improvements in the theoretical methods for calculating the expected value instead led to a shift in predictions, where theory and experiment now align. It was another great opportunity for a challenge to the Standard Model, but the results instead showed that the Standard Model’s predictions indeed agreed with reality instead.

This image, composed of two figures from the Muon Theory Initiative’s 2025 white paper, shows at top the differences between theory and experiment depending on which leading order hadronic vacuum polarization input is used. The green results are all r-ratio (experimental data input) inputs, while the blue lines are all lattice QCD inputs. The WP25 designation reflects what’s chosen in the 2025 white paper, with the lower table showing the differences between the 2020 and the 2025 white papers.

Credit: R. Aliberti et al./Muon Theory Initiative, arXiv:2505.21476, 2025

So where do we go from here? Does this mean the Standard Model simply holds?

We’ve explored other avenues where it might not hold, and yet, our experiments just keep agreeing with what’s predicted. We narrowed down the mystery of neutrino masses to be within their tightest set of windows ever this year, and they show no hint of doing anything “novel” other than oscillating between the three known, expected flavors that exist. There are still good reasons to believe that perhaps neutrinos will someday shed some light on our current mysteries of the Universe, but that day hasn’t yet arrived here in 2025.

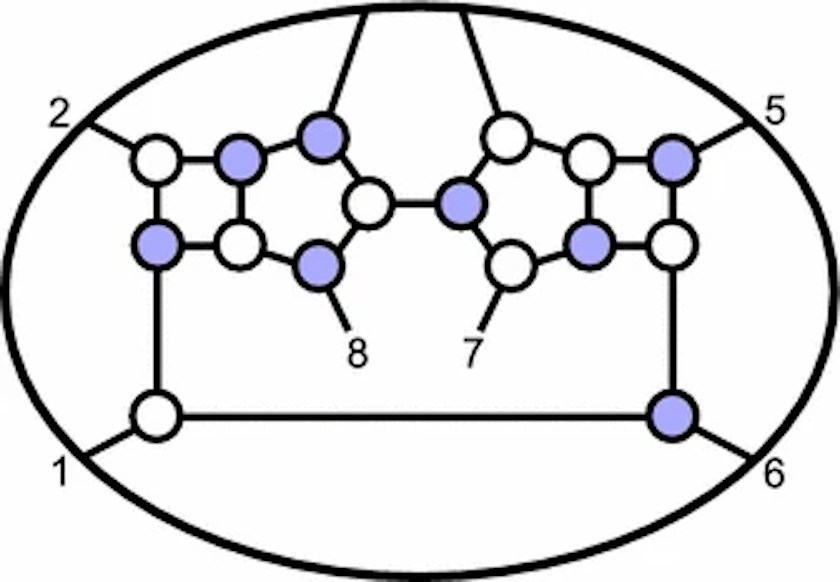

What about theories that go beyond the Standard Model, or extensions to it? One popular idea that gained traction in 2025 is known as positive geometry, purporting to be a path towards a theory of everything. This may turn out, someday, to be a fruitful endeavor, but for right now it’s just another idea in the sandbox: one among many that hopes to reproduce the Standard Model’s successes while explaining phenomena that the Standard Model cannot account for. However, there are very good reasons to think that, like many other theories that encapsulate but extend the Standard Model, this one will make predictions that don’t align with reality as well.

Although this picture looks very different from a conventional Feynman diagram, and also doesn’t look very much like a conventional geometric object, it encodes a framework, within the field of positive geometry, for calculating the scattering amplitude of a many-particle interacting system. This on-shell diagram helps connect the mathematics of Grassmannian manifolds with scattering amplitudes.

Credit: B. Chen et al., European Physical Journal C, 2017

Sure, there are always new theories that get proposed, but with the rise of LLMs, more and more ill-motivated theories are seeing the light of day, increasing the noise in an already noisy sea where theorists are desperately searching for even a hint of real signal. On the front of the origin of matter, our best bet for probing the unknown frontier is still to build a new, more powerful particle collider: a scenario that’s looking less and less likely as public sentiment turns away from long-term investment in fundamental science for short-sighted alternatives that may turn out to be nothing more than the latest bubble of unfulfilled promises.

Over on the cosmological side, the same set of puzzles persists:

- the origin and nature of dark matter,

- the properties and constancy (or not) of dark energy,

- and the origin of the matter-antimatter asymmetry,

plus other mysteries that have arisen purely based on observations:

- the controversy over the cosmic expansion rate,

- the origin of cosmic dust,

- the abundance and brightness of early galaxies,

- whether the untested predictions of cosmic inflation describe our reality,

- and whether dark energy is evolving or not, with this last one particularly driven by recent DESI observations.

Many have already decided for themselves — whether it’s actually true or not — that there are far too many puzzles, and far too many hints that the Standard Model is insufficient, for the consensus picture to hold.

This animation of DESI’s 3D map of the large-scale structure in the Universe, the largest such map to date, was created with the intention of studying dark energy and its possible evolution. However, although they found evidence for dark energy evolving, that’s likely due to the assumption that it’s dark energy’s evolution that’s causing the discrepancies in the data compared to our standard cosmological model. This is not necessarily the case.

Credit: DESI Collaboration/DOE/KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Proctor

But that’s not necessarily how we decide matters on scientific grounds. In particular, a large number of suggestive observations and theoretical tensions — at low significance individually — is a scoundrel’s tactic when it comes to scientific arguments. Instead, it’s the most robust data that’s most significant, and that leads us to deciding any matter that’s controversial.

For example, as far as DESI’s results are concerned, which is all about the question of whether dark energy is consistent with a cosmological constant or whether the data indicates some sort of evolution in dark energy’s properties, the significance simply isn’t there. DESI is the largest-ever deep large-scale-structure survey ever conducted, revealing galaxies, galaxy clusters, and the cosmic web more comprehensively than ever before.

And yet, on its own, the “evidence” for evolving dark energy from DESI is only about 2-σ significance, whereas 5-σ is required to announce a discovery. Only by combining it with other data sets, like the CMB and supernova data, does the significance increase, and even then, not anywhere near that 5-σ threshold. (Moreover, combination with some supernova data actually reduces the significance.) It may yet turn out that dark energy does evolve, of course, but we will have to await evidence from larger, more comprehensive surveys: from Vera Rubin, Euclid, SPHEREx, and the upcoming Nancy Roman Telescope.

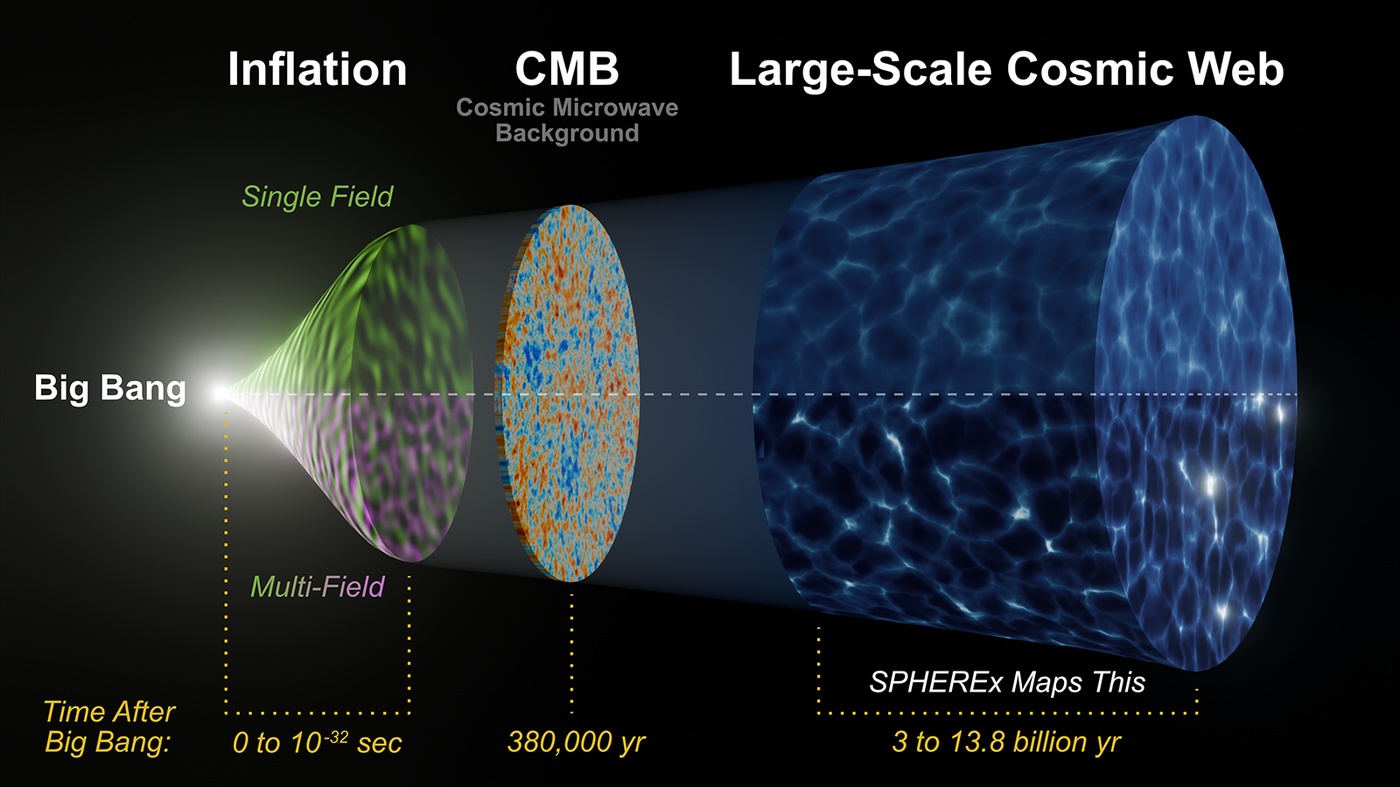

In the aftermath of inflation, signatures are imprinted onto the Universe that are unmistakably inflationary in origin. While the CMB provides an early-time “snapshot” of these features, that’s just one moment in history. By probing the large variety of times/distances accessible to us throughout cosmic time, such as with large-scale structure, we can obtain information that would otherwise be obscure from any single snapshot.

Credit: Caltech/Robert Hurt(IPAC)

Many have questioned whether cosmic inflation is the correct picture for setting up and initiating the hot Big Bang, and criticisms of inflation abound, including from one of its co-founders. However, those criticisms can’t undermine inflation’s successes, including:

- its prediction of spatial flatness to a level of 99.99% or better,

- its borne-out predictions of a maximum temperature at the start of the Big Bang that’s well below the Planck scale,

- its prediction of a spectrum of seed fluctuations that’s nearly, but not quite, scale invariant,

- where the fluctuations are adiabatic and appear on super-horizon scales,

none of which can be accounted for by a hot Big Bang without an inflationary past. The evidence supporting inflation is overwhelming, and that’s why it’s just as well-accepted among professionals as dark matter or dark energy.

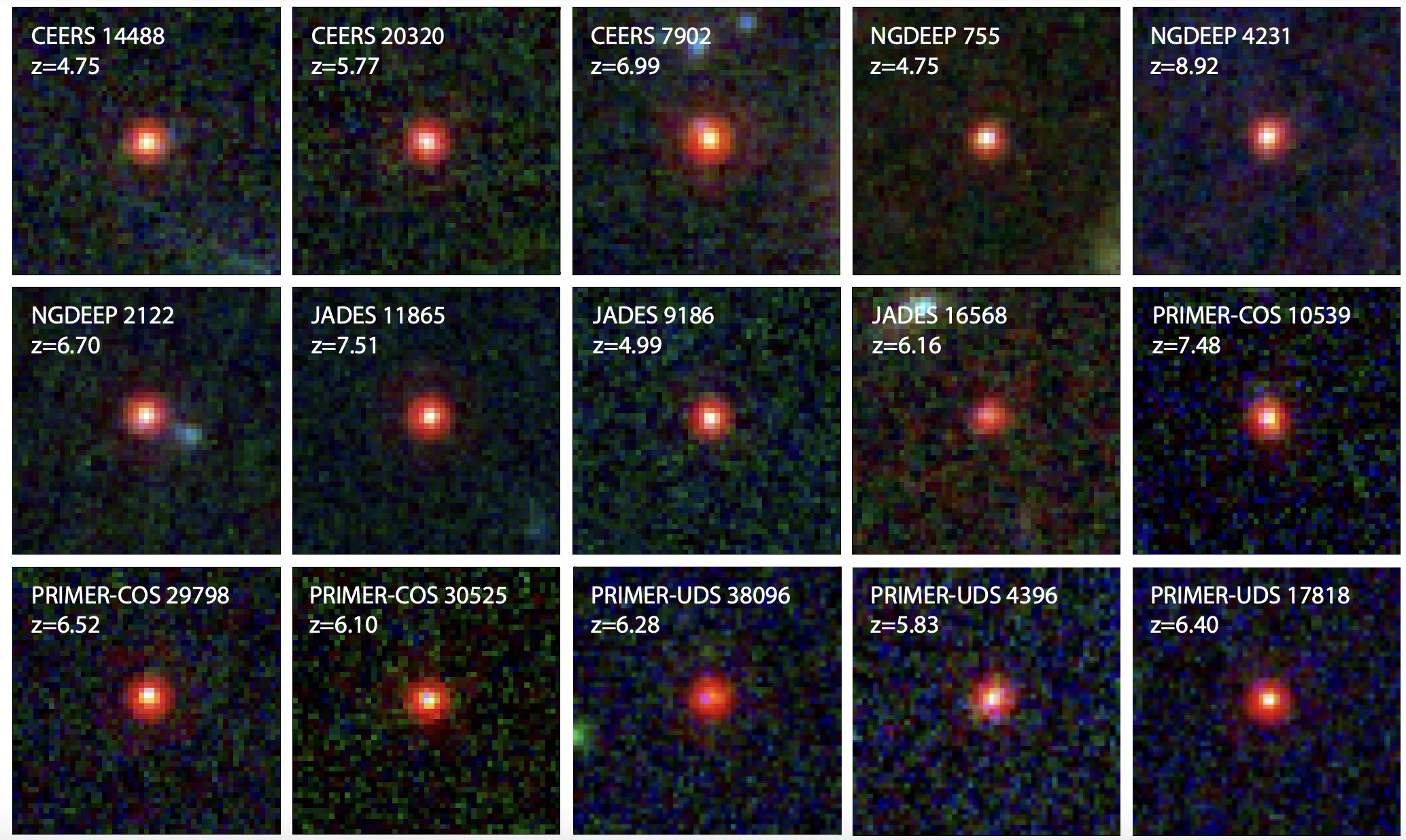

In the ultra-distant Universe, we’ve seen more distant galaxies than ever before, including breaking the record for the single most distant galaxy ever discovered here in 2025. Many have claimed that these early, distant galaxies, which appear in great abundance, have falsified the Standard Model of cosmology. But again, that’s not what the actual science indicates. We’ve instead learned that a combination of standard structure formation, with the key ingredient of dark matter, can indeed produce the objects we see when we see them so long as we account for the dual phenomena of bursty star-formation and brightness enhancements due to the activity of a central, supermassive black hole. These early galaxies, sometimes known as “little red dots,” are congruent with our Standard Model of cosmology.

This image shows 15 of the 341 hitherto identified “little red dot” galaxies discovered in the distant Universe by JWST. These galaxies all exhibit similar features, but only exist very early on in cosmic history; there are no known examples of such galaxies close by or at late times. All of them are quite massive, but some are compact while others are extended, and some show evidence for AGN activity while others do not.

Credit: D. Kocevski et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters accepted/arXiv:2404.03576, 2025

These early galaxies, and in particular how many of them ought to be supernova factories, can also explain the abundance and appearance of the cosmic dust that shows up early on. This cosmic dust is unevenly distributed across cosmic time, with low-dust galaxies, known as GELDAs, representing:

- 83% of all galaxies younger than 550 million years,

- 26% of galaxies between 550 million and 1.5 billion years old,

- and virtually no galaxies older than 1.5 billion years old.

Many times over the course of the year, people have come along with assertions that challenge the standard picture that dark matter exists. And yet, we know a Universe without dark matter would be very different than the one we observe, and there are several observational facts that are deep and profound that would be contrary-to-fact without the existence of dark matter.

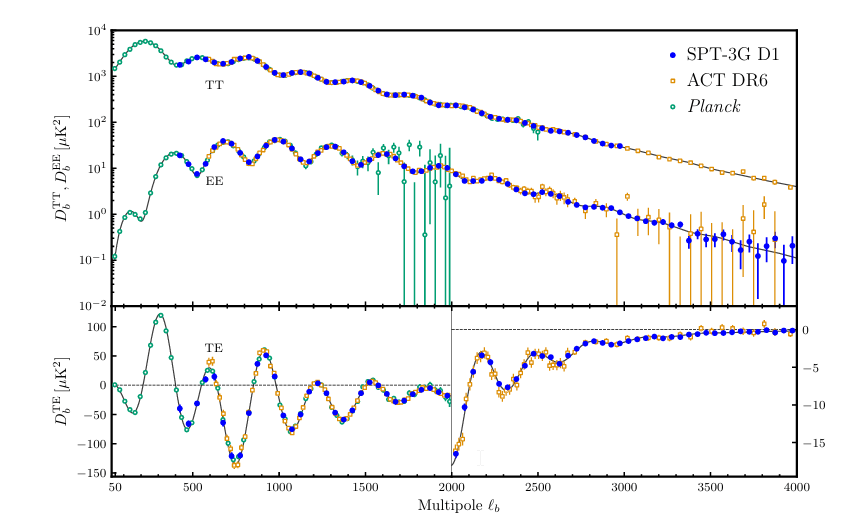

Similarly, people have questioned whether the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, is truly of cosmic origin. But it has definitively been demonstrated that those non-cosmic origin explanations fail spectacularly for the CMB, and the fluctuations in the CMB specifically provide extraordinarily strong evidence that they are not related to the dusty, star-rich structures that form at far later periods in cosmic history.

This graph shows the angular scales of CMB fluctuations as measured by Planck, ACT, and SPT down to the smallest angular scales ever probed: about 2 arc-minutes in angular scale. For contrast, the little red dot galaxies seen are all on sub-arc-second scales, more than 100 times smaller in angular size and 10,000 times smaller in angular area than the smallest measured scales of the CMB.

Credit: E. Camphuis et al. (South Pole Telescope collaboration), arXiv:2506.20707, 2025

Meanwhile, on the black hole front, we’ve now seen hundreds of merging black holes with gravitational wave detectors such as LIGO, and those observations remain consistent with the Standard Model of cosmology; there are no indications from that data that our current picture of the Universe needs revision. And despite the assertions of famous credentialed charlatans, the newest interstellar interloper in our Solar System, Comet 3I/ATLAS, is nothing more than exactly that: an interstellar comet. It shows no signs of new physics, alien technology, unusual accelerations, or any other of the specious claims that have been associated with it.

But there is one puzzle that has remained important, and may yet truly be a hint of new physics: the Hubble tension. Despite a famed, even legendary, astronomer’s claims that we haven’t yet reached the significance to declare that the Hubble tension is a real problem for cosmology, the facts are that practically every way we have of compiling a distance ladder measurement all points towards the same conclusion: that the Universe is expanding far faster than the “early relic” methods of the CMB or BAO yield. Instead of 67 km/s/Mpc, they yield 73-74 km/s/Mpc or greater, creating a puzzle regarding the contents of the Universe and causing us to question whether dark energy is constant.

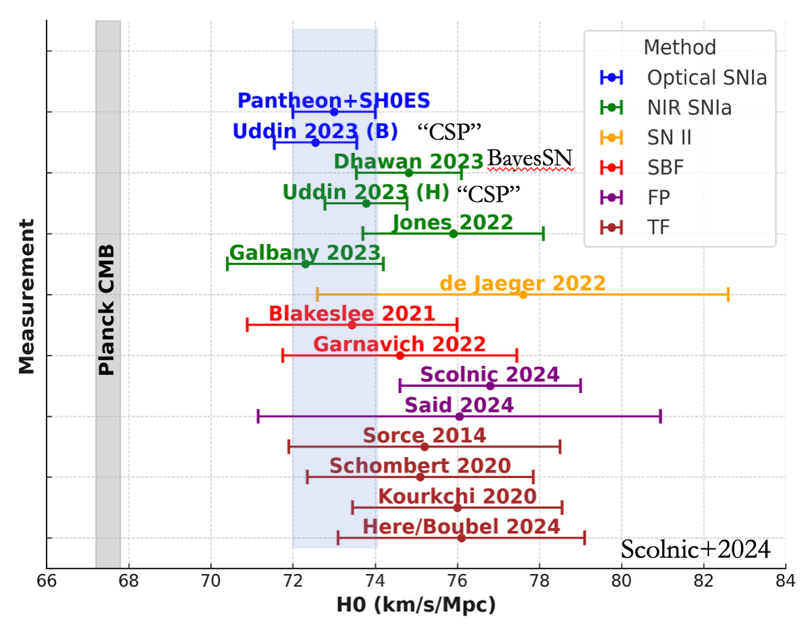

A compilation of distance ladder measurements of H0 in comparison to the Pantheon+SH0ES, where the third rung of the distance ladder is redone using various techniques. The legend shows the different techniques included in constructing this figure. For comparison, the “early relic” methods of CMB and BAO yield a value of 67 km/s/Mpc, inconsistent with distance ladder measurements.

Credit: D. Scolnic et al., RNAAS submitted/arXiv:2412.08449, 2024

Here at the end of 2025, if all you’ve done is consume popular science news, you might come away with the impression that the Standard Model — both of particle physics and of cosmology — is riddled with holes, and that many different teams of researchers have discredited it fully. That couldn’t be further from the truth; the Standard Model has repeatedly faced the most vociferous of attacks, by more who seek to knock it down, and beaten them all back with the largest suite of the highest-quality data ever collected. While puzzles certainly abound regarding what we currently understand and know, the Standard Model barely has any cracks in it at all.

Sure, we’d love to uncover the full explanation behind the Hubble tension. We’d love to know whether the DESI evidence is the harbinger of a coming revolution, or just a blip in the data. We’d love to know what the nature of dark matter and dark energy are, and how the cosmic matter-antimatter asymmetry was created. We’d love to know what the true underlying properties of neutrinos are, and whether they’re related to any or all of these puzzles. And we’d love to replace speculation about what could lie beyond the Standard Model with knowledge: with data that clearly indicates the answer.

All of that requires investing in science. In new experiments, new observatories, and in probing the frontier of fundamental physics beyond where we’ve ever probed before. Will we build new colliders, new space-based and ground-based observatories, new detectors, and the new facilities needed to answer the deepest of our questions? The options is there for us to grow our knowledge in novel ways: this year and every year to come. Whether we go down that road or not, collectively, is up to all of us.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.