Observations of AT 2024wpp reveal that luminous fast blue optical transients are driven by extreme stellar destruction—not supernovae

Maunakea, Hawaiʻi – Astronomers analyzing data from an array of telescopes, including the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi Island, have determined that luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBOTs) are powered by an extreme tidal disruption event—one in which a black hole up to 100 times the mass of the Sun completely shreds its massive stellar companion within days.

Observations of the event AT 2024wpp provide the clearest evidence yet that these rare cosmic flashes are not unusual supernovae, but instead require a powerful central engine driven by black hole accretion. The discovery challenges existing models of black hole physics and advances our understanding of stellar evolution.

The mystery of fast blue optical transients

Among the more puzzling cosmic phenomena discovered over the past few decades are brief and extremely bright flashes of blue and ultraviolet light that rapidly fade, leaving behind faint X-ray and radio emissions. With only slightly more than a dozen detected so far, astronomers have long debated whether LFBOTs are produced by an unusual type of supernova or by material falling into a black hole. The brightest event observed to date shows they are neither.

“Its extreme luminosity makes AT 2024wpp the brightest of all LFBOTs,” said Natalie LeBaron, graduate student at UC Berkeley and lead author on one of the studies that analyzed the optical, ultraviolet and near infrared emissions of the object. “For the first time we have confirmed that these transients require some sort of central energy source beyond what a supernova can produce normally on its own.”

LeBaron and the team infer the existence of this extra central engine energy source because AT 2024wpp radiated an amount of energy in the first 45 days, which is 100 times greater than what is radiated in a normal supernova over a longer timescale.

AT 2024wpp is analyzed in a pair of studies led by the University of California, Berkeley and published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

AT 2024wpp, a luminous fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT, is the bright blue spot at the upper right edge of its host galaxy, which is 1.1 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: Aidan Martas/UC Berkeley

AT 2024wpp, a luminous fast blue optical transient, or LFBOT, is the bright blue spot at the upper right edge of its host galaxy, which is 1.1 billion light-years from Earth. Credit: Aidan Martas/UC Berkeley

A flash too powerful to be supernova

The inferred mass of the black hole — in a range sometimes referred to as intermediate-mass black holes — is also intriguing for astronomers. While black holes of more than 100 times the mass of the Sun are known to exist because their mergers have been detected by gravitational wave experiments, they have never been directly observed, and how they grow to this size remains a major open question.

“Theorists have come up with many ways to explain how we get these large black holes,” said Raffaella Margutti, UC Berkeley associate professor of astronomy and physics. “LFBOTs allow you to get at this question from a completely different angle. They also allow us to characterize the precise location where these things are inside their host galaxy, which adds more context in trying to understand how we end up with this setup — a very large black hole and a companion.”

How a black hole destroys a star

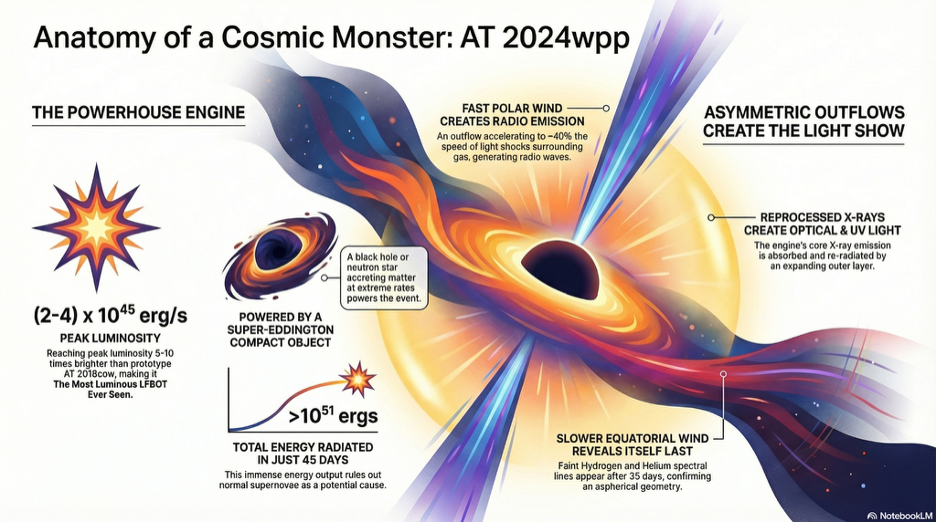

Researchers hypothesize that the intense, high-energy emission from AT 2024wpp arose from a long-lived black hole binary system that had been siphoning material from its massive companion for an extended period. This process likely surrounded the black hole in a halo of gas too distant to be immediately consumed.

When the companion star finally ventured too close, it was torn apart by tidal forces. The newly disrupted material became entrained in the black hole’s rotating accretion disk, slamming into existing gas and producing powerful bursts of X-ray, ultraviolet, and blue light. Some of the material was funneled toward the black hole’s poles and ejected as jets traveling at roughly 40 percent the speed of light, generating radio waves when they collided with surrounding gas.

The shredded companion star was likely more than ten times the mass of the Sun and may have been a Wolf–Rayet star—an evolved, extremely hot star that has already lost much of its hydrogen. This scenario naturally explains the weak hydrogen emission observed from AT 2024wpp.

Keck Observatory uncovers key clues

The team used Keck Observatory’s Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) to detect extremely faint signatures of hydrogen and helium in the event’s light. These signals appeared multiple times and showed an unusual double-peaked pattern, indicating = the explosion was not evenly shaped but instead lopsided and complex.

Observations from Keck Observatory’s Near-Infrared Echellette Spectrograph (NIRES) uncovered another critical clue. Roughly 24 days after the explosion, Keck Observatory detected an unusual excess of near-infrared light—only the second time such a feature has been observed in this rare class of events. Follow-up observations from Gemini Observatory confirmed the finding, suggesting that this infrared glow is likely a defining characteristic of LFBOTs.

This finding strengthens the case for future mid-infrared observations of similar events, which could help reveal the physical processes responsible for this mysterious glow.

“Studies like AT 2024wpp are only possible because of rapid, highly coordinated observing campaigns across many telescopes, both on the ground and in space,” said LeBaron. “While working on this object, we were very excited to be able to combine observations in optical, ultraviolet, infrared, X-ray, and radio light so that we could fully piece together a much more complete picture of what powers these extraordinary explosions — something no single telescope could do on its own.”

While LFBOTs are extremely rare (on average, astronomers discover about one per year) there is hope for LFBOT enthusiasts. The next generation of observatories such as the Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) and NASA’s Roman Space Telescope will dramatically increase the number of discoverable LFBOTs.

“This new era of time-domain astronomy will allow us to uncover many more hidden explosions and use them to probe extreme physics and black holes across the universe,” said Nayana A.J., UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow and lead author on the companion study on the analysis of X-ray and radio emissions.

LFBOTs are truly cosmic monsters, powered by the shredding of a massive star by a black hole the mass of 100 suns. An LFBOT discovered last year, AT 2024wpp, provided the data astronomers needed to narrow down the origins of these bursts. This graphic explains how the shredded star interacted with the accretion disk already existing around the black hole to produce the huge amounts of energy radiated at high-energy wavelengths. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC BerkeleyRelated Links:

LFBOTs are truly cosmic monsters, powered by the shredding of a massive star by a black hole the mass of 100 suns. An LFBOT discovered last year, AT 2024wpp, provided the data astronomers needed to narrow down the origins of these bursts. This graphic explains how the shredded star interacted with the accretion disk already existing around the black hole to produce the huge amounts of energy radiated at high-energy wavelengths. Credit: Raffaella Margutti/UC BerkeleyRelated Links:

ABOUT LRIS

The Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS) is a very versatile and ultra-sensitive visible-wavelength imager and spectrograph built at the California Institute of Technology by a team led by Prof. Bev Oke and Prof. Judy Cohen and commissioned in 1993. Since then it has seen two major upgrades to further enhance its capabilities: the addition of a second, blue arm optimized for shorter wavelengths of light and the installation of detectors that are much more sensitive at the longest (red) wavelengths. Each arm is optimized for the wavelengths it covers. This large range of wavelength coverage, combined with the instrument’s high sensitivity, allows the study of everything from comets (which have interesting features in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum), to the blue light from star formation, to the red light of very distant objects. LRIS also records the spectra of up to 50 objects simultaneously, especially useful for studies of clusters of galaxies in the most distant reaches, and earliest times, of the universe. LRIS was used in observing distant supernovae by astronomers who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011 for research determining that the universe was speeding up in its expansion.

ABOUT NIRES

The Near-Infrared Echellette Spectrograph (NIRES) is a prism cross-dispersed near-infrared spectrograph built at the California Institute of Technology by a team led by Chief Instrument Scientist Keith Matthews and Prof. Tom Soifer. Commissioned in 2018, NIRES covers a large wavelength range at moderate spectral resolution for use on the Keck II telescope and observes extremely faint red objects found with the Spitzer and WISE infrared space telescopes, as well as brown dwarfs, high-redshift galaxies, and quasars. Support for this technology was generously provided by the Mt. Cuba Astronomical Foundation.

ABOUT W. M. KECK OBSERVATORY

The W. M. Keck Observatory telescopes are among the most scientifically productive on Earth. The two 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes atop Maunakea on the Island of Hawaiʻi feature a suite of advanced instruments including imagers, multi-object spectrographs, high-resolution spectrographs, integral-field spectrometers, and world-leading laser guide star adaptive optics systems. Some of the data presented herein were obtained at Keck Observatory, which is a private 501(c) 3 non-profit organization operated as a scientific partnership among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.