In 1963 the Queen Mother wrote to Cecil Beaton thanking him for his many photographs of the royal family: “We must be deeply grateful to you for producing us, as really quite nice and real people!” Beaton’s great skill was not to record reality, but to tinker with it until it reached its perfect pitch. Whether he was turning the royal family into fairytale kings and queens, or Second World War officers into brooding matinee idols, or horsey debutantes into stylish society women, Beaton had a special ability to take real life and make it into the best version of itself.

As Robin Muir reveals in Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World, a sumptuous book written to accompany the National Portrait Gallery exhibition, Beaton’s fascination with transformation started early. As a 19-year-old he told his diary, “I don’t want people to know me as I really am, but as I am trying and pretending to be.” The real Cecil had been born in 1904 to a London timber merchant and a mother descended from Cumbrian blacksmiths. At Harrow and Cambridge, though, he acquired the necessary sheen to infiltrate the Bright Young Things, that group of decadent young aristos whose shenanigans involving sex, drugs and jazz garnered outraged headlines round the world. The starstruck Beaton lost no time in making friends with such people as Nancy Mitford, Diana Cooper and Stephen Tennant and photographing them in preposterous poses: : Cooper as a nun and Tennant as Prince Charming.

Diana Cooper as a nun

© CECIL BEATON ARCHIVE/CONDÉ NAST

Closer to home, Beaton dressed up his two younger sisters like frou-frou costume dolls and photographed them against an improvised backdrop of tinsel, vases, bed sheets and birdcages. The effect was that of a fête galante by Watteau and delivered the desired result. Baba and Nancy Beaton became fixtures in Tatler and married into “society”, with the latter becoming Lady Smiley. Less successful was young Cecil’s attempt to get the family’s house near Paddington Station upgraded; his request that its postcode should be reclassified from W2 to W1 fell on deaf ears.

Following his sisters into an upwardly mobile marriage was never an option for Beeton, whose love affairs were mostly with men (one unhappy exception was an obsessive fling with Greta Garbo). Nonetheless, he made sure that his male friendships came with benefits. Beaton’s portrait of Georgie “Dadie” Rylands, the celebrated Cambridge academic, posing as the Duchess of Malfi was the first of his pictures to appear in Vogue. Within three years he was under contract to the magazine, an extraordinary achievement for a 23-year-old from W2. Muir, who also curated the NPG exhibition, puts this meteoric ascent down to Beaton’s “limitless ambition, a tireless capacity for hard work and a rapacious eye”.

Greta Garbo, 1946

© CECIL BEATON ARCHIVE/CONDÉ NAST

That rapacious eye was initially drawn to society women. Beaton’s favourite models carried the whiff of night-time decadence about them: stick-thin, sharp of eyebrow with the kind of pale complexion that suggested a chronic lack of sunlight. In the late 1920s his favourite was Paula Gellibrand, the Marquise de Casa Maury, whom he photographed as “The Gilded Lilly” in a shimmering sheath of a dress and with a slightly sinister wreath of white lilies round her shingled head. It was, though, the Marquise’s tiny lipsticked lips that really entranced him: “Her small mouth, a butterfly stamped upon her face, looks completely useless except for kissing crucifixes and flowers.”

Beaton was, unsurprisingly, no shrinking violet when it came to appearing in front of the camera. One of the most disturbing images in this book shows him in full drag posing persuasively as the risqué romantic novelist Elinor Glyn. It is at this point you remember that one of his nicknames was “Malice in Wonderland”. A more candid portrait from 1937 shows him wearing a suit garlanded with multiple photographic self-portraits. This visual jesting owes much to the surrealist artists, especially Jean Cocteau, whom Beaton encountered during his working trips to Paris in the 1930s. (It was Cocteau who came up with the wonderful Malice tag.) You can see this influence too in images such as Hats Are High (1936), in which the model’s disembodied head appears to spring out of a hatbox stuffed with tissue paper.

The Second World War arrived just in time. A stint on American Vogue had ended in disgrace in 1938 when Beaton was caught smuggling an antisemitic slur into one of his illustrations (his whimsical sketches of high society were equally in demand at the magazine). To everyone’s surprise, not least his own, he turned out to be both practical and brave in his post as official photographer to the Minister of Information.

• The real Cecil Beaton — ‘He was a little bit scary and terribly sweet’

Enduring uncomfortable and often dangerous conditions, he sent back images from India, the Western Desert of Africa, the Middle East and China. His most important work, though, involved documenting the devastation of the London Blitz. In September 1940 he took a photograph of a three-year-old casualty, Eileen Dunne, in her hospital bed, cradling her doll and staring in incomprehension at the viewer. When the image appeared on the cover of Life Magazine it did much to convince America to join the hostilities.

Beaton working on the set of My Fair Lady, 1963

© CECIL BEATON ARCHIVE/CONDÉ NAST

After the war he became a sought-after designer for stage and screen, culminating in his double win at the 1964 Oscars for his work on My Fair Lady (one for costumes, the other for art direction). You can’t help noticing how the transformation that Eliza Doolittle, played by Audrey Hepburn, undergoes from street hawker to society lady echoed his own journey from Beaton Brothers Timber Merchants to the undisputed arbiter of international high style.

Nowhere was this pre-eminence put to better use than in Beeton’s work with the British royal family. The abdication in 1936 had damaged the institution’s legitimacy and it was Beaton’s job to establish George VI, his wife, Queen Elizabeth, and their two princesses as the best people to step into the breach. Beaton’s shrewd strategy was to turn them into a fairytale version of themselves.

While his earlier photographs of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor had shown a sharp-edged glamour couple, he turned their replacements into a cosy Ruritanian dynasty decked out in gold brocade and frills. His 1939 photograph of the Queen Mother was titled Faerie Queen, and showed her in a fluttery costume and holding a frilly parasol. Young Princess Elizabeth, at this time heir to the throne, is dressed in puff sleeves and posed in what appears to be a painted woodland grove. Here was artifice, deployed so skilfully that, as the Queen Mother hinted in her letter of thanks, it was better than the real thing.

• Read more book reviews and interviews — and see what’s top of the Sunday Times Bestsellers List

Muir has had access to thousands of luscious images in Beaton’s archive and that of Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue. He shrewdly buttresses all that fabulousness with brief and elegant essays on aspects of Beaton’s life and work. Muir takes admirable care neither to gush nor wag his finger at a man whose attitudes and sensibilities do not exactly align with our own, yet whose artistry never fails to deliver great scented blasts of pleasure.

Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World at the National Portrait Gallery runs until Jan 11

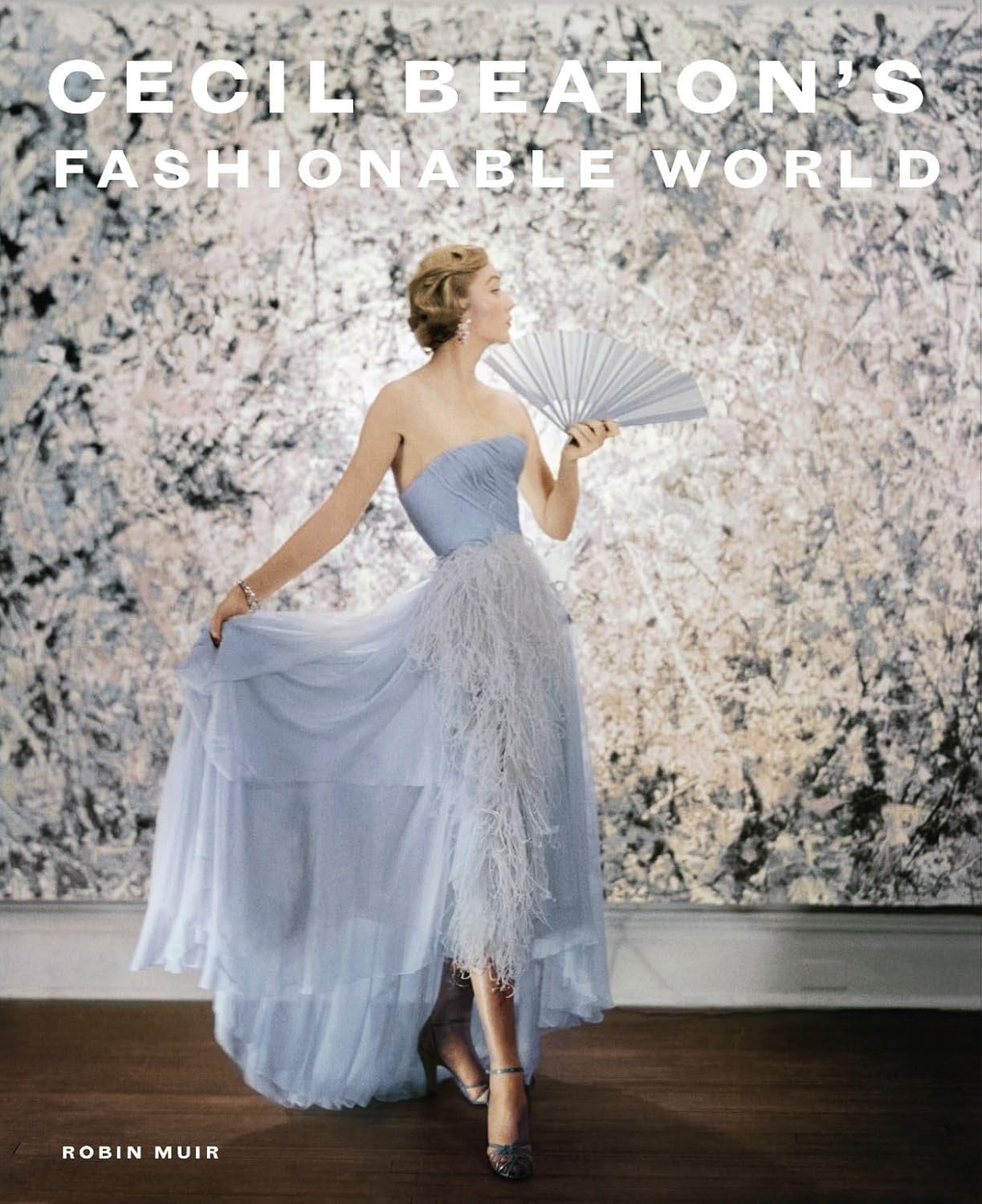

Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World edited by Robin Muir (National Portrait Gallery £40 pp288). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members