The research revolves around zirconium, a rare element found in meteorites, which has provided a surprising clue about how material from supernovae, exploding stars, reached the inner Solar System. By studying meteorites, Bizzarro and his colleagues found evidence that much of the supernova material was captured in ice as it traveled through the interstellar medium, rather than riding on grains of stardust as previously believed.

Supernova Remnants in Ice

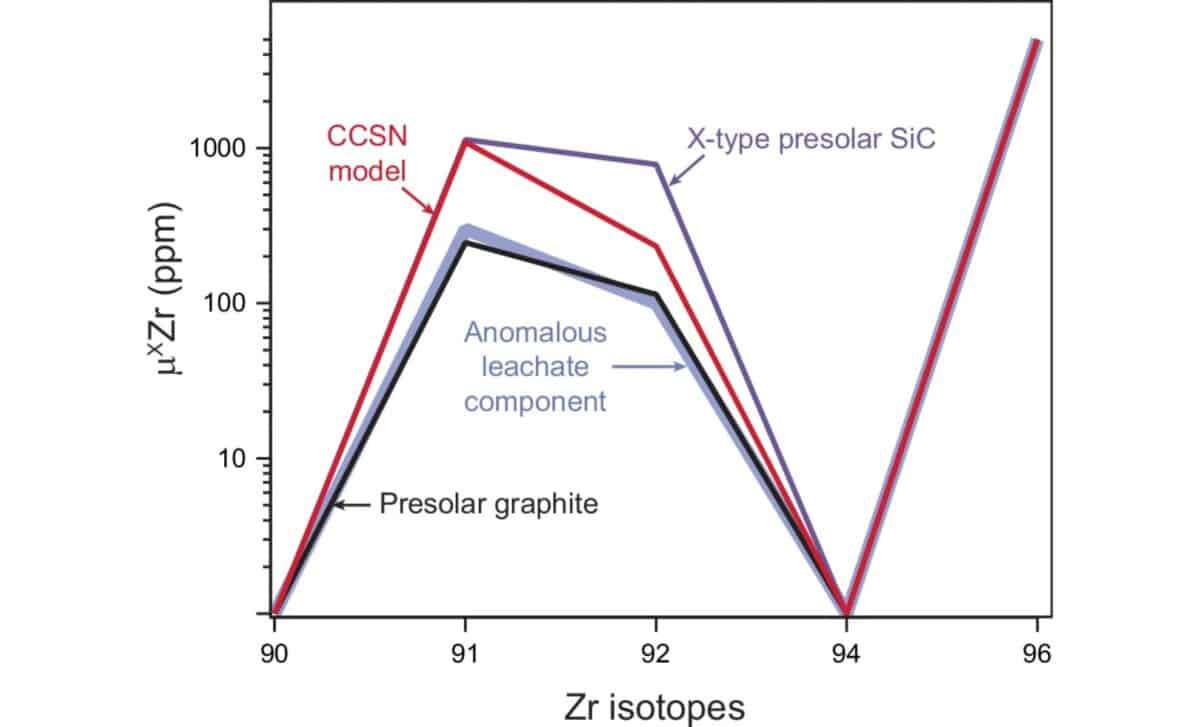

The cornerstone of Bizzarro’s study is the discovery of zirconium-96 (Zr-96), an isotope that can only be created in supernovae. According to the research, Zr-96 was present in much higher concentrations in the leachates (the material dissolved by acetic acid) than in the solid residues of meteorites. This suggests that supernova remnants were embedded in interstellar ice grains, which were then incorporated into meteorites and later into planets.

Previous studies had suggested that the heavy elements in supernovae, which include isotopes like Zr-96, were transported through space as “stardust,” tiny grains of material that eventually coalesced into planets. But Bizzarro’s team found that a significant amount of these remnants were captured in icy particles, which are more volatile and susceptible to being destroyed closer to the Sun. As the research explains, this new finding alters the theory of how Earth and other planets were formed.

Planet Formation and Pebble Accretion

This shift in understanding has major implications for how we think about planet formation. Traditionally, scientists believed that planets like Earth formed when large asteroids or protoplanets collided. However, the new study supports the “pebble accretion” model, which proposes that tiny icy particles gradually accumulated to form planets. These pebbles would have sublimated as they neared the Sun, releasing gases that carried isotopes like Zr-96 away before they could accrete onto the growing planet.

According to Bizzarro’s findings, Earth’s relatively low concentration of Zr-96 compared to outer planets like Neptune and Uranus aligns with this theory. The inner planets would have lost much of their supernova material as these icy pebbles evaporated, leaving behind a less isotopically rich planet.

The Snow Line and Solar System Composition

Another interesting revelation from the study is the role of the “snow line” in shaping the composition of planets. The snow line, which marks the point in the protoplanetary disk where temperatures were low enough for water to freeze, seems to have been a boundary for ice-rich materials. According to the paper published in Nature, planets forming beyond this line would have more ice and, therefore, higher concentrations of supernova isotopes like Zr-96. Conversely, planets forming closer to the Sun, where temperatures were higher, would have had less access to these icy particles.

The varying concentrations of Zr-96 in meteorites from different parts of the Solar System further support this theory. As Bizzarro’s research shows, bodies closer to the snow line, such as Mars and the asteroid belt, have more supernova isotopes than those nearer the Sun, such as Earth and Venus.

Bizzarro’s paper not only shifts the narrative on how planets are formed but also opens the door to further questions about how materials from different parts of the galaxy interact with planetary systems. The discovery that supernova material may have been preserved in ice could have a lasting impact on both the fields of planetary science and cosmochemistry.