The study, conducted by a team from North Carolina State University, Princeton, and Texas A&M University, was published in Nature Communications. Their work shows that atomic oxygen can persist in water for tens of microseconds, reaching depths of hundreds of micrometers. This unprecedented observation could force scientists to rethink existing models of solvated atomic oxygen’s reactivity and transport in liquid environments.

Atomic oxygen, a highly reactive form of the element, is crucial in various medical and industrial applications due to its oxidative properties. Yet, despite its importance, the way it behaves in water remained largely speculative. That’s because water rapidly quenches excited oxygen atoms—deactivating them before they can be recorded—making previous measurement attempts unsuccessful.

Laser-Induced Fluorescence Captures Fleeting Atomic State

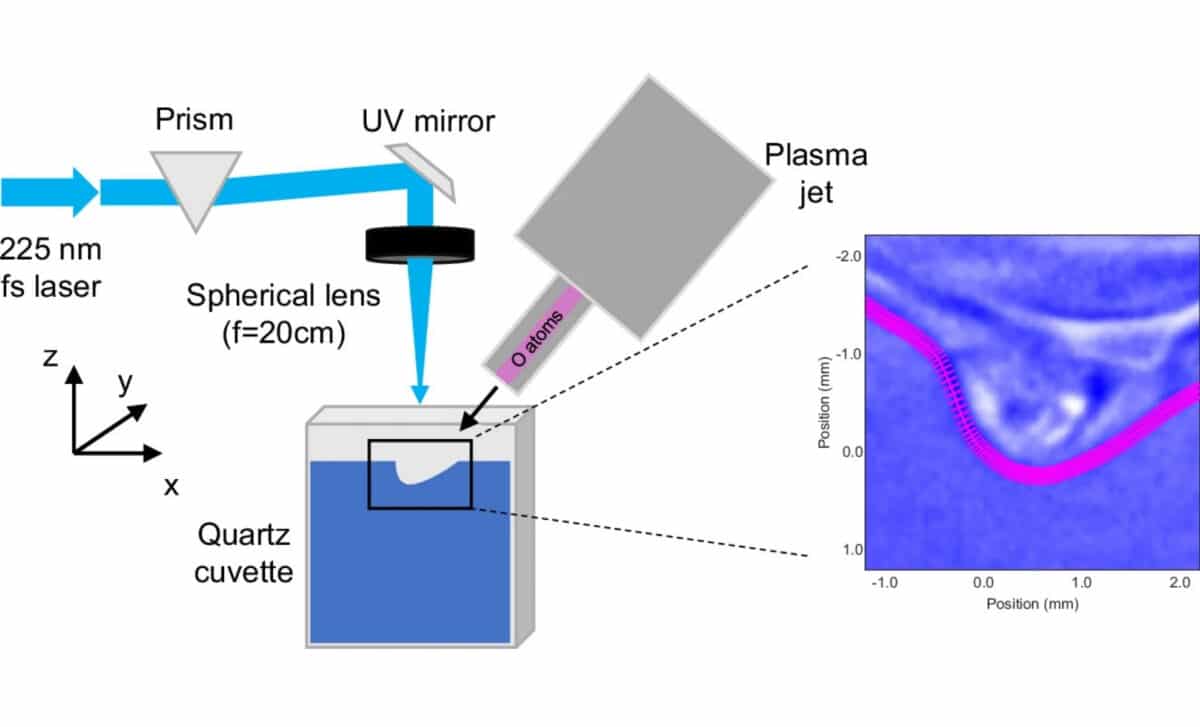

To finally observe atomic oxygen in water, researchers turned to two-photon absorption laser-induced fluorescence (TALIF), a technique that relies on atomic excitation and the detection of emitted light. In this method, oxygen atoms are forced to absorb two photons simultaneously, pushing them into an excited state. As they return to a stable ground state, they emit fluorescence, which scientists can measure to determine their presence and concentration.

Typically, this process is ineffective in water due to rapid quenching. But the team overcame this by using a femtosecond laser, which emits pulses lasting just one quadrillionth of a second. This allowed them to excite the atoms faster than the surrounding water could quench them, capturing the fluorescence signal in a brief but critical window.

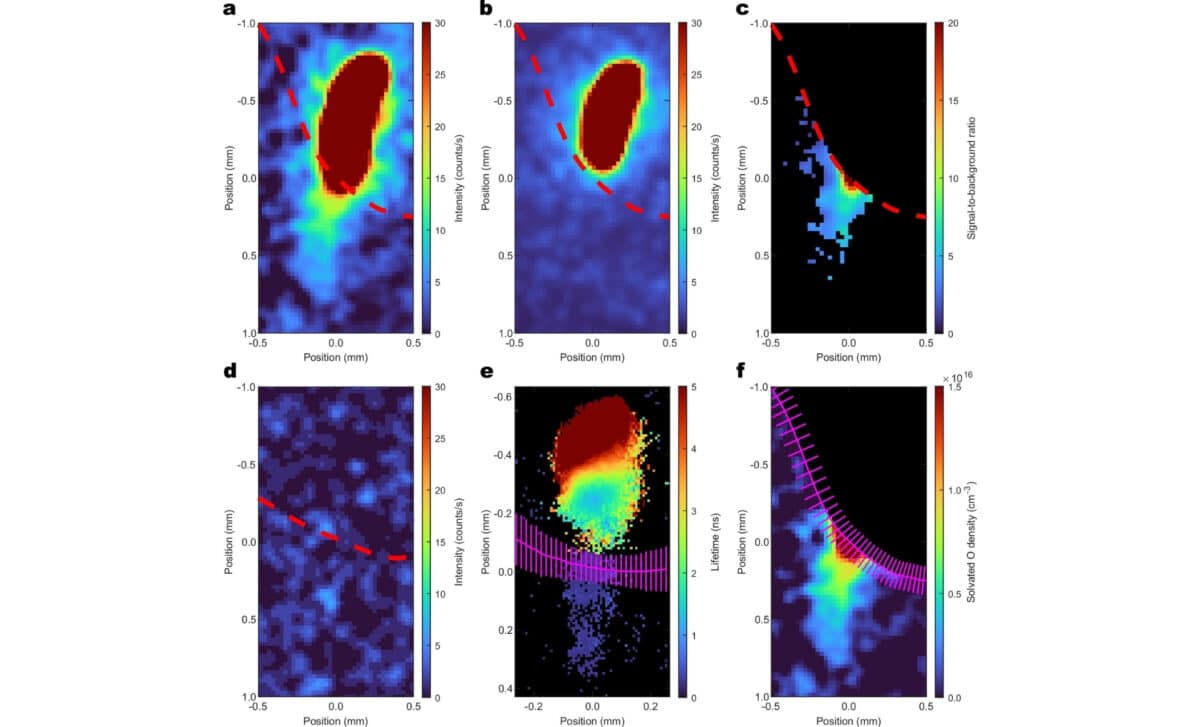

The fluorescence data was then compared to a calibrated xenon density signal, as xenon exhibits a nearly identical two-photon excitation and fluorescence behavior. This comparison helped simulate how often the excited atoms collided with water molecules, which led to an estimated density of 10¹⁶ atoms per cubic centimeter near the water’s surface.

Unexpected Longevity and Penetration Depth

Beyond confirming the presence of atomic oxygen, the study uncovered surprising details about how it moves and behaves in water. According to the authors, oxygen atoms persisted for tens of microseconds, a considerable duration for such a reactive species, and penetrated hundreds of micrometers into the liquid.

This level of persistence was previously thought to be impossible. The researchers noted that such longevity has significant implications for how scientists understand oxygen’s reactivity in aqueous environments. Existing theoretical models will need to be revisited to accommodate this new evidence of extended lifespan and transport distance.

Upper-Bound Estimates and Methodological Limits

While the findings mark a major advancement, the researchers acknowledged key limitations in their methodology. One critical assumption is that any collision between the excited oxygen atoms and water molecules leads to immediate de-excitation. If, in reality, some collisions occur without quenching, the estimated densities would represent upper-bound approximations, not exact values.

The study also aimed to evaluate the effective branching ratio, the fraction of excited atoms that emit a photon. Since the experiment measured only fluorescence-emitting atoms, any atoms that were excited but failed to emit detectable light were excluded from the data. This narrows the scope of the conclusions but also highlights the complexity of measuring such transient chemical phenomena.

Still, the ability to detect atomic oxygen in water at all marks a fundamental shift. According to Popular Mechanics, this success opens the door for future research that could refine current models and expand our understanding of oxygen chemistry in liquid environments, a subject once thought too fleeting to study directly.