In the middle of the North Atlantic, far from any coastline, lies a sea with no land boundaries. Instead of being framed by continents, its edges are defined by four major currents circling in a wide gyre. The water inside is calm, warm and unusually clear. Its surface often glitters with floating golden-brown seaweed. Its name is not well known outside maritime science, but what happens there increasingly matters.

This region, known as the Sargasso Sea, has long been considered an oceanic anomaly. Remote and undisturbed, it serves as a habitat for species found nowhere else and a crossroads for marine migration. For scientists, it offers a natural observatory for studying long-term environmental change in the open ocean.

Recent research based on four decades of monitoring has identified subtle but accelerating shifts in the sea’s physical and chemical makeup. Temperatures have climbed, pH levels have dropped, and salinity patterns have altered, all signs of global change reaching into one of the ocean’s most stable zones.

Ocean Acidification and Temperature Trends Confirmed

Long-term data from the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study (BATS) indicate that the surface of the Sargasso Sea has warmed by 0.97°C since 1983. Over the same period, ocean salinity rose by 0.136 units, and dissolved oxygen declined by 12.49 µmol/kg, equivalent to a 6 percent reduction.

These findings, published in Frontiers in Marine Science, confirm consistent upward trends in both heat and salinity. The study also recorded a significant increase in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), which rose by 51.5 µmol/kg, alongside a steady drop in pH by 0.072 units, confirming the presence of ongoing ocean acidification.

The Sargasso Sea’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere remains intact, but the chemical consequences of that absorption are becoming more evident. As CO₂ dissolves in seawater, it reacts to form carbonic acid, lowering pH and reducing the availability of carbonate ions. These ions are necessary for marine organisms to build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate.

The Revelle factor, a measure of the ocean’s resistance to further CO₂ absorption, also increased during the study period. This indicates that the sea is becoming less capable of continuing to absorb carbon without undergoing further acidification.

Carbon Cycling Affected by Rising Emissions

The Sargasso Sea is known for its role as a carbon sink, absorbing CO₂ and sequestering it in deep water through biological processes. However, the BATS data show that this role is shifting under pressure from anthropogenic emissions.

Surface fugacity of CO₂ (fCO₂), which reflects the gas’s partial pressure in seawater, rose by 19.4 µatm per decade. Using a chemical tracer method known as TrOCA, researchers estimated an increase in anthropogenic carbon of 42.7 µmol/kg across the study period. The majority of the rise in DIC—over 70 percent—can be attributed to human-generated CO₂.

Stratification in the water column, caused by warming, is now limiting vertical mixing. This reduces oxygen transfer and restricts nutrient circulation to deeper layers, which in turn affects primary production in surface waters. The result is a decline in the ecosystem’s capacity to support marine food webs.

Floating mats of Sargassum seaweed, once thriving nurseries for juvenile turtles, porbeagle sharks, and migratory eels, are now more exposed to environmental stress. As acidity increases and carbonate saturation declines, species that rely on shell-building processes face a more challenging environment.

The study’s authors write that “the ocean chemistry of the 2020s is now outside the range observed in the 1980s,” underscoring the scale of the long-term shift.

Human Activity Compounds Environmental Shifts

The physical isolation of the Sargasso Sea has not shielded it from human impact. Its position within the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre causes it to accumulate marine debris carried by surrounding currents. Estimates published by Earth.com indicate that concentrations of plastic pollution can exceed 500,000 pieces per square mile.

Increased shipping traffic through the area has added pressure. Noise from engines interferes with the communication of marine mammals such as sperm whales, and propeller turbulence damages Sargassum mats. Discarded fishing gear often entangles marine animals that depend on the floating seaweed for protection and food during early life stages.

Despite these pressures, there is no international authority with legal jurisdiction over the Sargasso Sea. It lies entirely in international waters, limiting the scope for national conservation action.

The Sargasso Sea Commission, created through the Hamilton Declaration in 2014, serves as a coordinating body. It promotes science-based policy and advocates for precautionary management, including seasonal protections and proposed rerouting of shipping traffic. However, the commission has no enforcement powers.

A Critical Indicator for Broader Ocean Change

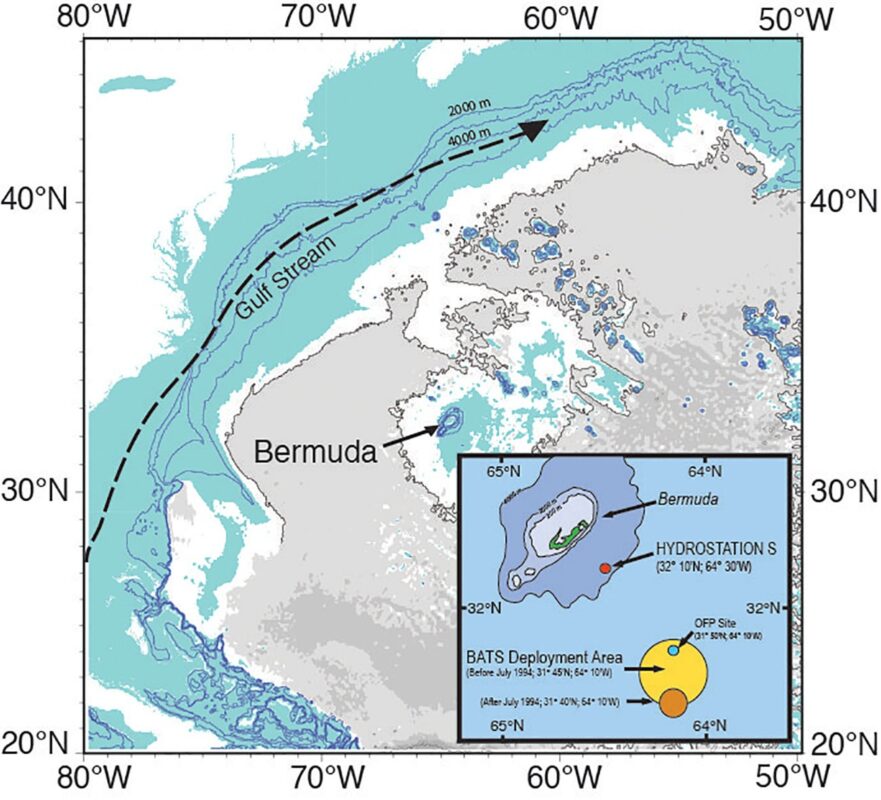

What makes the Sargasso Sea unique also makes it important. Its stability, location and well-documented history give scientists a rare baseline for tracking the impacts of climate change on the open ocean. The time-series data from BATS and Hydrostation S are among the longest continuous ocean datasets in the world.

This region supports the early life stages of several migratory species. Both European and American eels spawn here before travelling thousands of miles to freshwater habitats across the Atlantic basin. Changes to the sea’s temperature and chemistry could interrupt these life cycles.

Shifts in ocean heat content and circulation in the North Atlantic also carry wider implications for weather systems, storm tracks and precipitation patterns in Europe and North America.