History tells us who we are and how the past has shaped us. This is a commonly expressed truism, but in Ireland’s case, our history began later than most in Europe: ice sheets covered the country until about 10,000 years ago, making human habitation impossible. When the first settlers finally arrived after the ice retreated, they made up for lost time, with their descendants having a disproportionate effect on world culture and events. Let’s get into our time tunnel and visit a series of captivating attractions that tell the story of Ireland in nine memorable visits.

Lough Boora, Co Offaly

First stop is Lough Boora, a worked-out bog that has been rehabilitated as a visitor attraction and now serves as a diverse wildlife haven that can be explored by a series of walking/cycling trails. On the 9km Mesolithic Loop, you visit one of the earliest sites of human habitation in Ireland. Located on the shore of a great post-Ice Age lake, which covered much of the midlands, this was where our hunter-gatherer ancestors, who killed animals, fished and collected fruit and berries to survive, made temporary camp. Evidence of their charcoal campfires and flint tools has remained behind as proof of their coming. Considered hugely important by archaeologists, this site shows that Mesolithic people didn’t just hug the Irish coastline, as was once thought, but ventured far inland as they sought food sources. Admission free.

Céide Fields, Co Mayo The Céide Fields

The Céide Fields

Our time tunnel now skips us forward to the 1930s, where schoolteacher Patrick Caulfield is cutting turf in a north Mayo bog. He discovers linear lines of stones that were clearly not natural formations. This led to the uncovering of a vast Neolithic farming landscape, including ancient stonewalled fields, houses, and megalithic tombs. Dating back almost 6,000 years, the Céide Fields celebrate the seminal moment that civilisation began in Ireland. It was when our ancestors stopped wandering and settled down to become farmers and builders. An unlikely but spectacular location for Ireland’s biggest Neolithic site, it is now Europe’s oldest known field system. Here, you walk through time on the guided tour and learn how these ancient fields were frozen in time by an encroaching bog. Centred on a 4,000-year-old pine tree from the nearby peatlands, the visitor centre fills in any details you miss on the guided tour and has numerous interactive exhibits that will appeal to all ages. Adult admission €5.

Dún Chonchúir, Co Galway The ring fort of Dún Chonchúir, on Inishmaan

The ring fort of Dún Chonchúir, on Inishmaan

The Iron Age immediately preceded the Irish Christian Age and it is the era that gives us our great sagas and mythical figures, such as Cú Chulainn, Queen Maeve and Fionn MacCumhaill. The use of iron tools made life easier, but these could also be fashioned into weapons, which meant defensive structures were important. Stone forts are the best known and largest monuments from Ireland’s Iron Age. To view a fine example, head out to Inis Meáin on the Aran Islands, where the improbably huge Dún Chonchúir (O’Connor’s Fort) is a must-see attraction. It offers a 360-degree panorama from atop astounding stonewall defences, which now seem implausibly huge considering the subsequently impoverished history of the island. Admission free.

Clonmacnoise, Co Offaly Visitors at Clonmacnoise. Photograph: Cyril Byrne

Visitors at Clonmacnoise. Photograph: Cyril Byrne

Christianity brought profound change to Ireland, opening an insular society to new ideas and bringing with it literacy and learning, along with new forms of art and illumination. Newly established monasteries were at the forefront of this change, fostering learning, architectural innovation and the creation of illuminated manuscripts. Nowhere is the influence of early Irish Christianity more apparent than at Clonmacnoise. Set in an idyllic location on the river Shannon, it became a great seat of learning and attracted students from across Europe. This great monastic site gives a window into the flourishing of the Celtic Church, while much of Europe was in turmoil after the fall of the Roman Empire. Monks at Clonmacnoise were skilled craftsmen, producing illuminated manuscripts, including Lebor na hUidre, the oldest surviving text written in Irish. Adult admission, €8.

Waterford city Lana Elez and Dordana Gojic from Serbia take a seat on the Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife bronze sculptures beside the Bishop’s Palace in the Viking Triangle of Waterford City.

Lana Elez and Dordana Gojic from Serbia take a seat on the Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife bronze sculptures beside the Bishop’s Palace in the Viking Triangle of Waterford City.

Photograph: Alan Betson

So far, we haven’t encountered any towns or cities. Irish people, at this time, lived in widely dispersed rural communities based around kinship, with the largest population centres located near abbeys. Coming initially as plunderers of monasteries and social disrupters in the late 8th century, the Vikings eventually settled down to trade and created Ireland’s first urban centre at Waterford in 914. Today, their heritage is preserved amid the narrow medieval streets of an area known as the Viking Triangle. To get a deeper understanding of 10th-century Ireland, you can visit “King of the Vikings”, a virtual reality experience housed in a replica Viking home. This will transport you back over one thousand years to meet the legendary Viking King who founded Waterford. Later, you can explore the Viking Museum in Reginald’s Tower, showing artefacts from the Medieval Period. Adult admission, €12.

Cahir Castle, Co Tipperary

Now we enter the age of knights and castles, when the Anglo-Normans arrived in the 12th century. Their military superiority and use of castle building to hold territory ensured rapid advancement. One of the greatest Norman families was the Butlers of Ormond, who ruled over what is now Tipperary and Kilkenny. At Cahir, they built a great castle on a rocky Island in the river Suir, which was considered impregnable. On the guided tour, which children will love, you will be introduced to the many clever defensive features incorporated within the Castle. These, however, failed to anticipate the invention of the cannon. The Earl of Essex took three days to blast his way into the castle in 1599 and the myth of impregnability was gone forever. Eventually, most of the great Norman Families went native and became “more Irish than the Irish themselves” but not before they had brought many innovations to Ireland from cathedral building to hay making and extensive tillage farming. Adult admission, €5.

Battle of the Boyne Centre, Co Meath

Our next outing takes us upriver from Drogheda to the Battle of the Boyne site. By a country mile, the largest and most significant battle fought on Irish soil, it ensured thereafter that only a Protestant monarch would reign on the British throne. The visitor centre is presently closed, but there is a 15-minute audiovisual introduction to the battle. Then, it is out to walk the battlefield to see where King James made camp at Groggin’s Field and Oldbridge, where William’s forces ensured victory by forcing their way across the Boyne. The accepted narrative holds that Protestant William fought his papist, father-in-law and uncle James, who was supported by Louis XIV of France, to prevent Catholic rule over Britain. Reality was more complex. Fearing a French conquest of the papal states by Louis, the pope was on William’s side. But such is the way of history, myth is more powerful than fact. Admission free.

National Famine Museum, Co Roscommon

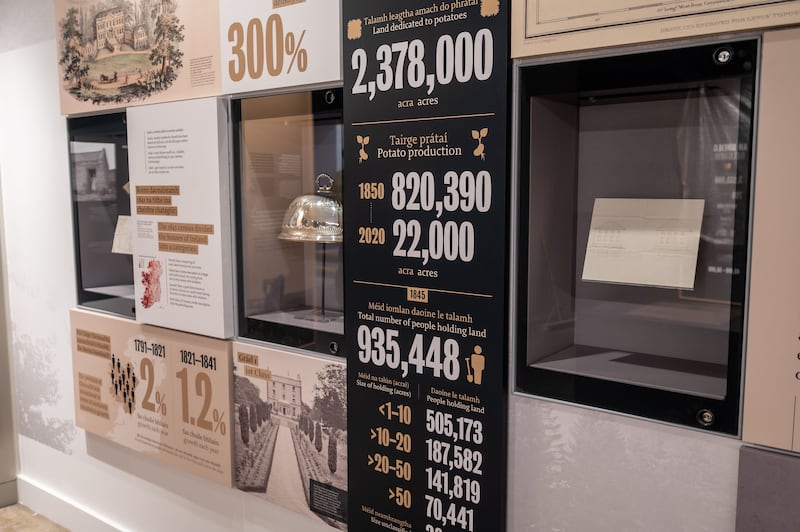

The Great Famine changed Irish life in a way that no other event has done. It halved the population, created a vibrant Irish diaspora, brought about a sharp decline of the Irish language and initiated a belief that landlordism was the root of Ireland’s social problems. At the National Famine Museum, you will encounter the two sides of this story. First, is Strokestown Park House to see how the ascendancy classes lived during the Famine. They weren’t starving, but they were floundering on the barbed wire of unpaid rents. Landlord Dennis Mahon responded with mass eviction and the transportation of 1,490 of his tenants to Quebec in 1847. Next, visit the Famine Museum housed in the former outbuildings of the estate. Here, you will learn how social structures in Ireland at the beginning of the 19th century made the country uniquely vulnerable to a potato crop failure. Adult admission, €5.

Museum of Country Life, Co Mayo

We return to Mayo now, to explore the Museum of Country Life, where history brushes close to the present. It tells a story of how ordinary people lived their lives in rural Ireland between the end of the Famine and the 1950s. In some ways, people were better off at this time because, after the Famine, there were fewer people and more land to go around. But life was unremittingly hard and the price of not saving the hay or the turf could be forced emigration. This was when almost everything was handmade and skilled craftspeople were crucial to the functioning of society, and the museum celebrates their workmanship. It also tells the story of those who made their living from the ocean and the many customs and traditions that built up around the annual festivals of Bealtaine, Lúnasa and Samhain. Admission free.