Scientific Paper

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and other radio observatories have detected dense gas surrounding one of the most energetic cosmic explosions ever observed. The findings show that material initially thought to be absent was present but rendered invisible to optical telescopes by intense radiation, becoming detectable only at radio and millimeter wavelengths.

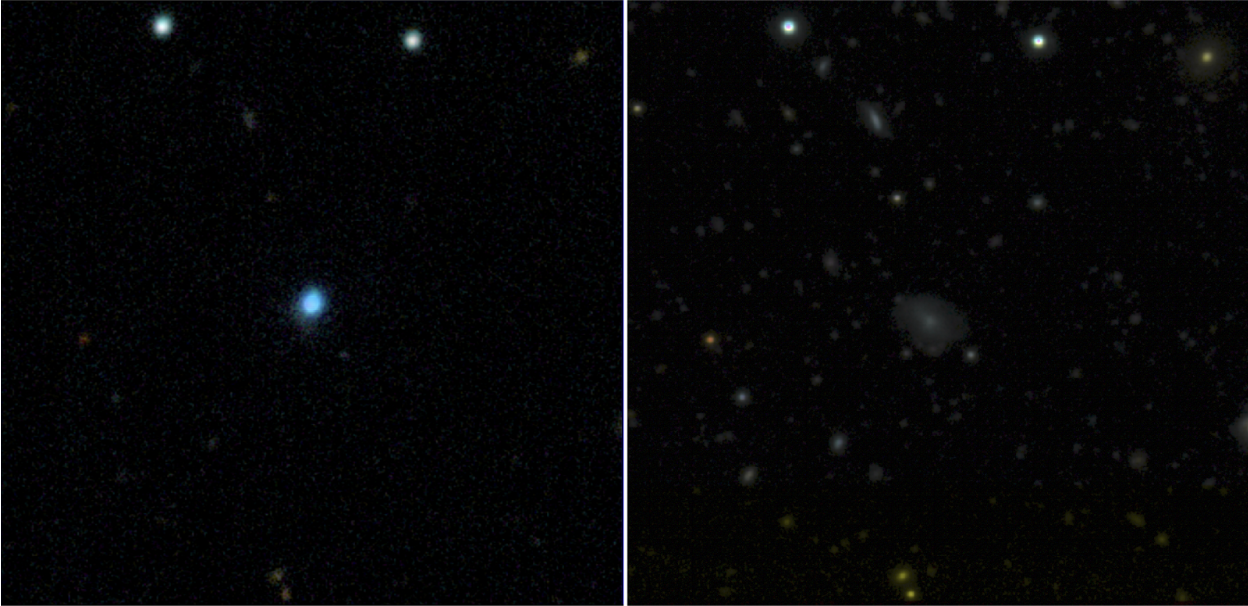

The event, designated AT2024wpp and nicknamed the Whippet, is a member of the rare class of Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients (LFBOTs). These events brighten and fade rapidly while releasing extremely large amounts of energy, exceeding those of typical stellar explosions.

“Even though we suspected what it was, it was still extraordinary,” said Daniel A. Perley, principal investigator of the study. “This was many times more energetic than any similar event and more than any known explosion powered by the collapse of a star.”

AT2024wpp was first identified in September 2024 by the Zwicky Transient Facility, with follow-up observations revealing a very hot, blue source emitting strong X-rays. Early optical data showed little evidence of surrounding material.

Radio and millimeter observations with ALMA and the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array revealed a fast-moving shock wave expanding at roughly one-fifth the speed of light into a dense region of gas close to the explosion. This gas was not visible at optical wavelengths because intense X-ray radiation stripped electrons from the atoms, suppressing traditional spectral signatures while leaving radio emission intact.

The observations support a scenario in which the explosion was powered by a massive black hole accreting material from a massive companion star. Prior to the final disruption, the star expelled large amounts of gas, forming a dense shell around the system. When the star was torn apart, the resulting debris produced the observed emission.

Subsequent spectroscopic observations detected high-velocity hydrogen and helium, providing further evidence for dense gas in the immediate environment of the explosion.

“Not only do these events help us identify black holes, but they also provide a new way to identify where black holes occur and how they form and grow, and the physics of how this happens,” Perley added.

Additonal Information

This research was published as “AT2024wpp: An Extremely Luminous Fast Ultraviolet Transient Powered by Accretion onto a Black Hole” by Daniel A. Perley et al., presented at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting this January.

This article is based on a press release by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory of the United States, an ALMA partner on behalf of North America, and the original press release from the Astrophysics Research Institute at Liverpool John Moores University.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan, and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of ALMA’s construction, commissioning, and operation.

Images

A new, extremely luminous fast blue optical transient, AT2024wpp, flares as a bright blue point of light in the left panel, located just off the edge of its faint host galaxy, while the right panel shows the same region of sky after the outburst faded. Credit: Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University/Daniel A. Perley

A new, extremely luminous fast blue optical transient, AT2024wpp, flares as a bright blue point of light in the left panel, located just off the edge of its faint host galaxy, while the right panel shows the same region of sky after the outburst faded. Credit: Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University/Daniel A. Perley