For 15 years, Seaver College’s Physics Department, under the leadership of professor

Gerard Fasel, has maintained Pepperdine’s strong presence at the American Geophysical

Union (AGU), one of the largest scientific conferences in the world.

Convening scientists from prolific research institutions such as NASA and leading

universities, AGU hosted Fasel, Seaver physics professor John Mann, and their undergraduate

researchers in New Orleans, Louisiana, from December 11 to 19, 2025. Named as a primary

convener, Fasel developed the session “Influence of Space Weather on Solar-Terrestrial

Interactions” in which the Seaver team presented related research and introduced a

new AI data recovery collaboration with Fabien Scalzo, Seaver computer science professor.

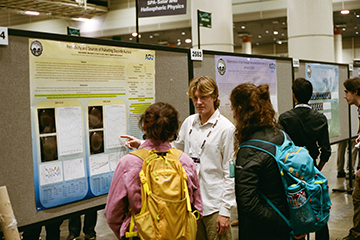

Seaver physics student explaining dynamics of daytime-occuring auroras

Seaver physics student explaining dynamics of daytime-occuring auroras

Space weather refers to activity from the Sun, such as solar winds and solar storms,

which affects the Earth and our neighboring planets. Coining the term “near-Earth

astrophysics,” Fasel has devoted much of his career to investigating solar-terrestrial

interactions between the Sun and Earth, using the aurora borealis to obtain clues

regarding the coupling mechanisms between the solar wind and the Earth’s terrestrial

magnetic field.

“Stars have winds,” says Fasel. “And this includes our Sun. While solar wind is a

relatively continuous stream of particles that interact with the Earth’s magnetic

field, the Sun can also produce powerful solar storms. These storms expel billions

of charged particles [plasma] coupled to magnetic fields, called coronal mass ejections,

which bang up into the Earth’s magnetic field.”

Satellite image of the aurora borealis from the International Space Station

Satellite image of the aurora borealis from the International Space Station

The Earth’s magnetic field lines, Fasel explains, “act like wires” on which these

particles travel down into the Earth’s upper atmosphere, specifically the ionosphere.

The aurora is an end result of this interaction, where high-energy electrons collide with oxygen to produce green

light, while those of lower energy produce a raspberry-red color. The aurora’s dancing

ripples, or striations, exist due to these magnetic field lines.

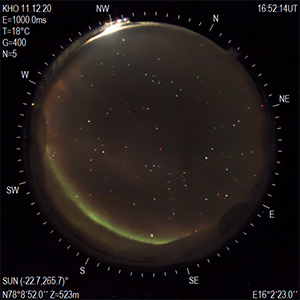

Photos captured at the Kjell Henriksen Observatory in Norway, together with images

from NASA spacecraft within the Earth’s magnetic field, provide data that help identify

patterns for predicting adverse space weather.

“We’d like to be able to forecast when we’re going to have a big burst of solar energy

hit the Earth’s ionosphere,” Fasel reflects.

During the AGU session he chaired, Fasel invited two close colleagues to present on

daytime auroras and related satellite-based models. Additionally, two more presentations

elaborated on his collaborative research efforts, one of which marked the culmination

of four years of research on solar wind discontinuities with Sun Lee of NASA Goddard.

The following discussion, “AI and Dayside Aurora BACC Data,” introduced the Seaver

team’s brand-new interdisciplinary research in the fields of AI and astrophysics developed

with Scalzo and Seaver computer-science student Jason Press.

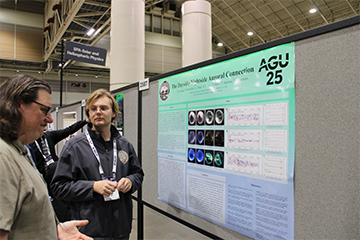

Jason Press speaking with Seaver physics professor John Mann

Jason Press speaking with Seaver physics professor John Mann

Demonstrating the broad applications of Fasel’s research, his collaboration with Scalzo

and Press has proved to be groundbreaking. During the summer of 2025, the trio purposed

funds from a sizable grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation to curate AI software that removes cloud formation from photos of aurora borealis

taken at the Kjell Henriksen Observatory. This new software opens the door for Fasel

to recover not only current data, but images from decades ago that were previously

scrapped due to cloud cover.

To train the AI model, Press explains that he and Scalzo fed the software two types

of images. One would be a clear photo of the aurora borealis and the other would be

altered with fake clouds. With this dynamic, the model was able to understand the

qualities of clouds and auroral light through comparison.

“We started off with the most simple form of clouds, and then we increased the complexity

of the images,” explains Press. “The model takes a cloudy image, and it gives what

it thinks is the correct response. Then we compare the model’s response to the actual

ground truth and that provides our overall loss. We train the model to minimize the

amount of loss.”

Restored image of an aurora (bottom left) from the Kjell Henriksen Observatory

Restored image of an aurora (bottom left) from the Kjell Henriksen Observatory

Then on December 18, Press took the AGU stage to present this technological breakthrough,

while Fasel served as the session chair/discussion moderator. “We were losing valuable

data,” Fasel explains. “There were a lot of times when we had cloudy weather, but

aurora still appeared on those days. I’d have friends from NASA reach out and ask,

‘Do you have this day of photos in your data?’ I’d look, and find that the auroras

were indistinguishable because of the clouds.”

When left unpredictable, solar-terrestrial phenomena can lead to adverse effects on

Earth. For example, the Carrington effect of 1859, the largest geomagnetic storm in

history, led to widespread blackouts and sparked fires in telegraph stations globally,

theorized to be due to a coronal mass ejection. Intensely bright auroras were witnessed

even in low-hemisphere locations such as Hawaii.

Seaver undergraduate researchers at AGU

Seaver undergraduate researchers at AGU

“Seaver faculty have created a strong culture of including undergraduate students

in their research programs,” says Lila McDowell Carlsen, vice provost and professor

of hispanic studies. “Dr. Fasel, Dr. Mann, and Dr. Scalzo’s collaboration with their

students is exceptional and provides a unique experience that will positively impact

their future trajectories. Another example is Sean Wu who worked with Dr. Scalzo and others on a number of medical applications of AI,

and Sean is now in Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. What is so special about Seaver is

that our faculty are conducting highly specialized research, and they bring their students along for every step of the way.”

In addition to Press’ contributions, a swath of Seaver students, accompanied by John

Mann, assistant professor of physics, presented eight poster displays as part of Fasel’s

Space Weather poster session. Topics spanned from observations of North-South auroral

arcs, the dimming and intensifying of dayside auroral pulsations, and the anatomy

of certain anomalies.

“Jason and Fabien made my idea into a reality,” says Fasel. “This technological breakthrough

presented at AGU, among many others, brings us closer to a deeper understanding of

space weather.”

Photo Credit:

Aurora borealis from the International Space Station provided by NASA astronaut Donald

Pettit

Aurora borealis from the Kjell Henriksen Observatory provided by Gerard Fasel

Conference photos provided by Jason Press