Photo: © Jill Greenberg, Courtesy Clamp Gallery

On a frigid December afternoon, I took an elevator up to the sixth floor of a midtown office building on a busy stretch of Eighth Avenue and walked into the lobby of Atlas Men’s Health. The clinic’s motto: DOMINATE THE DAY. Its website features a variety of AI-generated images of smiling women in athleisure and shirtless men, including one with bulging biceps holding an oversize photorealistic eggplant advertising the “Priapus Shot,” a penis injection for erectile dysfunction. The lobby had decorative touches you might call Temu neoclassical: a plastic olive tree, replica Greco-Roman busts, a Spartan helmet. The only other person in the room was the secretary, talking on the phone behind a large marble desk. “So your son has a bodybuilding competition coming up?” she said. “We can certainly help with that.” She rattled off names of compounds, long strings of letters and numbers; my ears perked up. These were what I’d come looking for: peptides.

I consider myself a complete idiot when it comes to health and wellness. I’ve never tried acupuncture, creatine, cupping, lion’s mane, Chinese herbal medicine, a neti pot, or nootropics. But over the past year, my rigid lack of interest in what other people are doing to their bodies started to crumble. The results were too noticeable. Friends and acquaintances were showing up at parties newly tan, ripped, skinny, with good skin. “I have so much energy! I don’t even drink coffee anymore,” they would say. “I fixed my stomach/sleep/ligament issues!” This wasn’t some big secret: They were injecting peptides and would happily tell you about their “stacks” and offer to connect you with their “plug.” I wanted in.

After a few minutes in the lobby at Atlas, the secretary led me into another room for my consultation with Mandeep Singh, a registered nurse at the clinic. He asked what my goals were. Weight loss? Muscle gain? Enhanced sexual performance? “Uh, I guess I get a little sleepy and distracted in the afternoon,” I said. Singh suggested a compound called NAD+. (Technically not a peptide but a coenzyme, it’s often sold alongside peptides at clinics like Atlas.) NAD+ “cranks up that electricity” that cells produce, Singh said. “Positive effects: bringing clarity, more energy, just a feeling of wellness, stamina.” Long term, there could be anti-aging benefits: “Every cell in your body is a little bit younger and healthier. We’re not going to turn you into Benjamin Button, but you’re just healthier overall.” He also suggested a peptide called tesamorelin, known for “turning up the volume on your natural production of growth hormone,” which could help me build lean-muscle mass. Unlike many peptides, tesamorelin is actually approved by the FDA, though only for helping HIV patients reduce abdominal fat.

I decided to stick with just the NAD+, which would require a twice-weekly shot, rather than the daily jab needed for tesamorelin. I paid $250 for a six-week supply, which showed up on my doorstep a few days later, shipped from a compounding pharmacy in Houston. I returned to the clinic for a lesson in at-home injection. The cheerful secretary — her AirPods still in — showed me how to reconstitute the dry powder in the vial with bacteriostatic water, measure out a dose, and inject myself in the soft tissue under my arm. I pushed the plunger down, and 100 milligrams of NAD+ surged into my body. (New York’s lawyers want me to be clear: I am not advocating for you to try this, and, certainly, I am not a doctor.) Half an hour later, on my couch at home, I felt a warm glow spread through my limbs, sort of like a milder version of the rush produced by Adderall. I pulled out my laptop and started writing some emails.

Peptides are the building blocks of proteins, consisting of between two and 100 amino acids linked together. They occur naturally in the body and affect the endocrine system, helping to regulate metabolism, mood, and energy. Insulin is a peptide; it was the first to be reproduced in a lab, in 1921. Since then, more than 80 others have hit the market, used to treat conditions including cancer, osteoporosis, multiple sclerosis, HIV, and chronic pain. Other compounds, including several of those now growing in popularity, were synthesized in the 1980s by Soviet scientists who used them to treat both Olympic athletes and Chernobyl survivors.

Peptides are the body’s messengers: They can tell skin cells to make more collagen, spur muscle growth after exercise, or affect immune activity. “There are some conditions where they work very well,” said Dr. Neil Paulvin, a physician who prescribes peptide therapies at his functional-medicine practice in Manhattan. “These include inflammation, gut health. And there are some conditions where they may provide small or no improvement.”

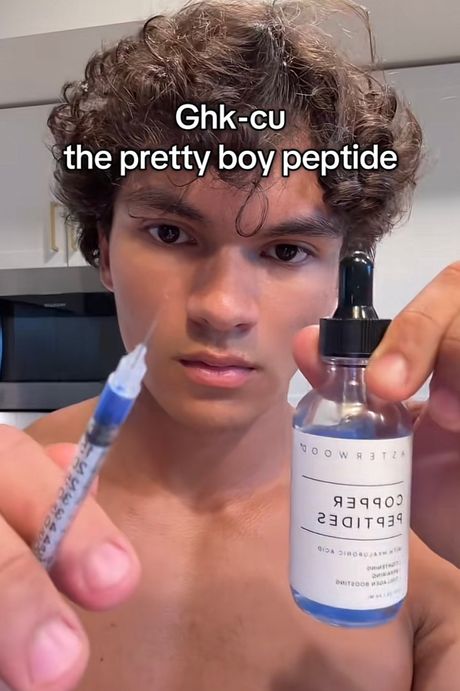

The global peptide-therapeutics market has swelled to over $50 billion in annual sales and is projected to nearly double again in roughly the next decade. The boom can largely be traced to the popularization of weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic and Wegovy; the P in GLP-1 stands for peptide. Their success helped normalize the idea of regular self-injection at home while opening the door — psychologically and commercially — for a wave of other compounds promising miraculous benefits. There are peptides marketed for just about every wellness and cosmetic outcome you might imagine. BPC-157, used for reducing inflammation and healing injuries, is also popular (Joe Rogan is a fan); so is GHK-Cu for anti-aging skin care. There are dozens more, sold for everything from quicker tanning (melanotan-II) to increased libido (PT-141).

Discord chat rooms buzz with users asking for advice on stacking and dosing protocols. On Reddit, where r/peptides has almost 140,000 members, people post pictures of their transformations. “The difference 4 months of peptides can make,” wrote one woman, captioning before-and-after images of her newly glowing skin and defined jawline. “My stack is TIRZ, GHKCU, KPV, NAD+, 5AMINO 1MQ, and LIPO C!”

Even before GLP-1 agonists brought peptides to the masses, off-label use of the compounds was common among bodybuilders, who have long experimented with exotic substances and documented the results. Adam Katz, 25, is a fitness influencer who goes by Coach Katz on social media. He has been bodybuilding since he was 14. In the past year, he said, many people in the fitness community began using Retatrutide, a weight-loss drug in development by Eli Lilly. It has shown immense promise in clinical trials: Patients lost on average around 50 percent more weight than those on the first generation of GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic. Yet to be approved by the FDA, it’s currently being synthesized illegally and sold through a sprawling gray market.

For the four months leading up to a bodybuilding show, Katz successfully used it to cut weight. This past May, he posted a video recommending Retatrutide for anyone trying to get “shredded for summer.” Now, he said, “you’ll see soccer moms and random people that don’t even go to the gym using Retatrutide.”

Recently, I spoke with a 34-year-old woman I’ll call Rachel, who was turned on to peptides after visiting L.A. and seeing a group of her friends who all looked amazing. “I was like, ‘What’s going on? Why do you guys all look so jacked and your skin is really tight and nice? You guys party constantly.’ ” Their response: “Oh, we’re all on peptides.”

Beyond being intrigued by the cosmetic benefits, Rachel was looking for help with the chronic knee pain she had spent a decade battling; the only thing that ever seemed to work was expensive, time-consuming acupuncture. Within weeks after she started using the peptides TB-500 and BPC-157, both known for promoting tissue repair and reducing inflammation, her knee was pain free. She started taking NAD+ and soon felt energetic and clear of the brain fog that had plagued her since a bout of COVID. It also made her skin bright and prevented hangovers.

Influencers across TikTok are selling peptides for every cosmetic and wellness concern—from weight loss to glowy skin, muscle gain, sexual performance, and more. Clockwise from top left: Photo: autisticclips8/TikTok; alexaaronn/TikTok; smoneyyz/TikTok; bricesmithhh/TikTok.

Influencers across TikTok are selling peptides for every cosmetic and wellness concern—from weight loss to glowy skin, muscle gain, sexual performance… more

Influencers across TikTok are selling peptides for every cosmetic and wellness concern—from weight loss to glowy skin, muscle gain, sexual performance, and more. Clockwise from top left: Photo: autisticclips8/TikTok; alexaaronn/TikTok; smoneyyz/TikTok; bricesmithhh/TikTok.

Many peptides are produced either by compounding pharmacies in the U.S. or by an ever-growing number of factories in China. The most serious users tend to get peptides from the latter for both a wider selection of products and cheaper prices.

John Ramsay has been sourcing doses from a factory called Xingruida Trade Co. for the past year. His path into peptides was fairly typical: After a stint in the military left him with lingering injuries, he went to a men’s clinic in Colorado for testosterone-replacement therapy; staff there suggested he try peptides for weight loss, but the $400-a-month price was out of reach. A job at a kratom company in Salt Lake City introduced him to a more DIY route: His “biohacker forward” boss hired a nurse to administer IV drips, and one day the nurse suggested adding NAD+. Ramsay tried it and woke up feeling unusually good — “I’m 47, so the days of feeling great get a little bit more limited,” he said — and soon started asking what else peptides might do. The nurse steered him to tirzepatide, the FDA-regulated GLP-1 marketed as Zepbound, which he got through a pharmacy.

This worked well but cost $500 a month. The nurse told him he could get the same drug for less from Paramount Peptides, one of many U.S. outfits that get around the FDA by saying their products are “for research only,” a loophole available as long as nothing is explicitly sold for human use. Ramsay began ordering from the site’s long menu. Retatrutide helped him shed more than 70 pounds in a year, and he added tesamorelin to burn visceral fat as well as a “Wolverine” blend of BPC-157 and TB-500 — touted for regrowing tissue — which he credits for faster surgery recovery. His health, he said, shifted dramatically: no more sleep apnea, no more blood-pressure meds, a healthier liver. The costs, however, were adding up. “First couple months out of the gate, I got really hyperfocused on it so I spent about a couple grand,” he said. “My wife’s like, ‘Babe, what are we doing? We got a freezer full of these fucking peptides all the time.’ ”

When TikTok and other platforms began feeding him ads for Chinese peptide factories, his deal-hunter instincts kicked in. He reached out to a seller on WhatsApp named Jasmine, and by this past March he was ordering directly from China. He bought tirzepatide and NAD+, sent samples to a third-party tester, and, after the results came back as advertised, “built a relationship with this peptide company.” The savings are enormous: A vial of tirzepatide that once cost him $480 through regulated channels can be had for around $20 from Chinese warehouses. American vendors and clinics are taking advantage of the price disparity. “Hormone-therapy clinics, longevity clinics, IV clinics, men’s clinics, fertility clinics, all of them — this is their gold-mine time,” Ramsay said. He has become a peptides guru to people he knows around Salt Lake and to the 190 or so who’ve joined his Discord channel. There, they can talk to his supplier; when they buy from her, John gets discounts on his peptides.

The Chinese companies themselves are happy to sell directly to consumers. My Instagram algorithm is flooded with their advertisements showing gleaming factories with thousands of peptide vials rolling off assembly lines. One ad, from a company called “Peptides fatory sale [sic],” promised, “When you find a reliable supplier, you wilt get a refrigerator full of peptides.” It included a link to chat on WhatsApp. I clicked on it and was soon texting with Yara, whose profile picture was an AI-generated image of a beautiful woman standing in a snowy cityscape. “Hey 👋 welcome! You’ve just connected with TeYi Company — direct factory peptide supply. ⚡Demand is crazy right now.⚡”

I responded saying I was an American vendor interested in purchasing large amounts of Retatrutide to resell stateside. How much could TeYi sell me? “We are a factory,” Yara wrote. “You can have as many as you want.” She attached videos showing large industrial freezers packed full of vials at the company’s Guangdong headquarters. She would happily sell me 10,000 20-milligram vials a month at $13.50 a pop. “We are airlifted. Don’t worry about customs,” Yara wrote. “We will give you a refund if you are detained.” The same quantity of Retatrutide from U.S.-based retailers typically costs anywhere from $150 to $400 per vial.

I started replying to every gray-market ad I got served, asking the dealers on WhatsApp — exclusively female avatars with pictures that seemed AI-generated — how much volume they could supply. A hundred thousand vials a month? “No problem, dear friend,” wrote Sophia, the representative from Huai’an Dinglin Trading. “We have our own factory. How long do you need to deliver?”

Judi, from Nanba Biotechnology Co., offered me a million vials a month at $10 each. I asked if her company had other customers in America buying that kind of volume. “Yes, my colleagues have them,” she wrote back. “But you’re the first person I’ve met who does. ⚡☺️”

The saleswomen were persistent. After I didn’t respond to one for a week, she followed up: “Hey friend. Peptide consultant Annie wishes you a happy life. Do you have any plans to order peptide medications in the new year?”

I must admit I have found myself enjoying my biweekly injection ritual: preparing the needle, sterilizing my skin with alcohol, the mild euphoria as the NAD+ courses through my bloodstream, the sense of alertness it provides without a comedown. I also felt the thrill of being an early adopter. In the past decade, we’ve all seen people willing to bet big on objectively stupid investments like dogecoin and $GME get rewarded for insane risk tolerance. For many young people, the feeling seems to be that they may be foolish not to make high-leverage bets with another extremely volatile asset: their own bodies.

Since I began searching for peptides on social media, my algorithm has been serving up an endless parade of comically jacked men and toned, tan women enthusiastically talking into their phones about better living through retail pharmacology. The surreality of these videos cannot be overstated. A young man with a low taper fade injects blue fluid into his stomach to a soundtrack of “Better Off Alone.” A young woman injects her boyfriend’s stomach while he stares at his phone, captioning the video “nursing school gf + peptide bf 🫶✨.” Miami influencers dance at a nightclub while bottle girls hoist a glowing sign that reads WHAT PEPTIDES YOU ON? The clip is captioned, “how life feels when we have random chinese research chemicals in our bloodstreams.” Typically, people making videos about peptides have affiliate links for peptide vendors in their bios. They are following the standard e-commerce playbook: Find something with an arbitrage opportunity via cheap overseas manufacturing and build a sales funnel from social media.

Influencers use cute words to dodge the moderators: peppers for peptides, ratatouille for Retatrutide. A real-estate agent in San Diego offers free NAD+ shots with a house tour. In a video titled “Day in the Life of a Peptide Millionaire,” an extremely tan, smooth-skinned man who calls himself “the Peptide King” talks about his industry. “Find what you’re good at and just scale the shit out of that,” he says while showing off his collection of Ferraris and Lamborghinis to the very young man interviewing him. This gold rush slots neatly into a lineage of Miami-adjacent hustle-influencer trend cycles — NFTs, drop-shipping, OnlyFans agencies. There’s one key difference: No one ever injected Bored Apes into their ass.

According to a source at one of New York’s elite prep schools, peptide use is rampant among students. They buy the compounds from TikTok influencers and hide the vials from their parents in mini-fridges they keep in their bedrooms. Students circulate TikToks, such as one in which a young woman stashes vials of peptides in what seems to be her family fridge, captioned “when ur mini fridge breaks so now u gotta hide ur peps behind sum ranch.” In another clip, a teenage user with the bio “16 year old on Mexican research chemicals” poses with a dog-ears filter. The onscreen text: “‘No bro we’re way too young to be pinning peptides’… …Translating 🔁 … ‘… Glory to the state of Israel! Long Live Benjamin Netanyahu!🇮🇱’”

The phenomenon known as “looksmaxxing” takes the peptide hype cycle past the point of absurdity. The subculture is built on a grim premise: Looks are destiny, and only those willing to undergo the most extreme interventions will win in work, dating, and life. Though women participate, this philosophy is geared ultimately toward the vanities and neuroses of young men. Looksmaxxers have developed their own language: “mogging” means out-classing someone’s appearance, to “ascend” is to transform your looks, and the “PSL scale” (an acronym referencing defunct looksmaxxing forums) ranks people from “subhuman” to “giga chad.” Peptides are ubiquitous. “Looksmaxxing is mostly about visible optimization and speeding up aesthetic results, so peptides get pulled in as tools that promise faster fat loss, better skin, and improved recovery,” said a 22-year-old college student I met in Ramsay’s Discord for peptide enthusiasts. “That’s where people like Clavicular come in, translating peptides into an aesthetic-first language that resonates with that crowd.”

Clavicular is the online alias of 20-year-old Miami-based influencer Braden Peters. In the past six months, he has become inescapable in certain corners of social media frequented by young men. His flat, affectless delivery evokes Patrick Bateman transplanted into zoomer streaming culture: wearing a hat with the N-word on it, mocking an OnlyFans model’s “horrible nasolabial folds” and “recessed maxilla” on a podcast, smashing his cheekbones with a hammer to reshape them, advocating jaw surgery, even taking meth to achieve a gaunt, hollowed-out look. He appeared to hit someone with his Cybertruck on a livestream. He danced at a Miami nightclub with the Tate brothers, Nick Fuentes, and other far-right figures to a Kanye West song with lyrics praising Hitler. On a stream with a teenage influencer who goes by the name Jenny Popach, Peters praised her for losing weight with Retatrutide — “Would you say that is the biggest thing for your ascension?” — and injected a fat-dissolving acid called Aqualyx into her face. (In response to fact-checking queries, Peters said our story included “internet rumors, clipped jokes, fabricated interpretations, and outright falsehoods,” though he also clarified specifics.)

All of this has turned him into something of an edgelord folk hero. “Clavicular stole the fire from the gods,” Fuentes declared on a recent stream. “In 2026, we’re all ascending, we’re all on peptides. We’re all working out. We’re all mewing, we’re all bone smashing.”

Peters’s profit strategy fuses shock-jock tactics with straightforward marketing. The looksmaxxers tell their young, insecure followers that their lives will be empty unless they submit to increasingly risky interventions, then sell them the solutions. Peters offers a paid course, including detailed advice on which peptides to take. For $49 a month, his fans can join “Clavicular’s Clan,” which promises “DETAILED GUIDES THAT WILL GUARANTEE ASCEND YOU!” There is, of course, a peptide vendor linked in his bio.

A peptide user’s supply.

Photo: Michael Friberg for New York Magazine

In the absence of clinical trials for these substances, users rely on anecdotal evidence and self-experimentation to determine whether they are effective. Roy Wersbe, 24, first tried the inflammation-reducing peptide BPC-157 a few years ago after hearing about it on X. Within two weeks, it cured a case of tennis elbow that had plagued him for years. “I was just, like, totally shocked,” he said. Wersbe started cycling through a variety of injectables that he buys from an online nootropics seller called Limitless. He believes big pharma and traditional medicine oppose peptides because they enable self-healing. “People just feel hopeless with the health-care system,” he said, “and are trying to take matters into their own hands.” Yet he’s uneasy about where the hype is heading — on a recent trip to the Huntington Beach farmers’ market, he saw someone selling peptides alongside fresh produce. “If people got super-sick this next year, I wouldn’t be surprised,” he said.

Thirty-three-year-old Trevor (a pseudonym) began using peptides after he hurt his Achilles tendon training for a marathon. He was sold BPC-157 and TB-500, which he was told to inject into his ankle. The first time, he felt some pain in his lower back. He kept taking the blend every other day as instructed. Within a week or two, the pain returned but much sharper. It was so bad, he said, he “fell to the floor. It knocked me out.” Trevor went to urgent care, where clinicians suggested he likely had kidney stones. “I was like, ‘Damn, that’s really what happens when you just fucking inject yourself with stuff,’ ” he said.

Forty-year-old Daisy (also a pseudonym) says the rotating stack of compounds she takes for joint pain has had an unexpected effect. “I went through like a second puberty on it,” she said. “I was just like jacked and had big boobs.” She compared one of her peptide blends — BPC-157 and GHK-Cu — to Compound V, the glowing blue fluid from The Boys. “It’s bright blue, looks insane, and burns when you inject it,” she said. She also tried intramuscular NAD+ shots deep into her thigh. “That one scared me — it makes your heart pound hard,” she said, noting it often sparks intense euphoria. “A lot of the people I know who like it are former heavy drug users who turned to wellness,” she said. “You have to be a little bit insane to do it.” It’s also a little ritual, and it “gives you something fun to talk about” at parties. “People love to compare stacks.”

Daisy views it as less extreme than cosmetic surgery, which is considered normal among her peers. “You’re gonna chop off part of your face and stitch it together to tighten your skin? That’s crazy, and it’s also really bootleg.” Still, she’s had mishaps — like after she injected into her ankle per Reddit advice. “I had really gnarly nerve pain for several days. I was like, ‘Fuck, did I permanently hurt myself because some random person on Reddit said something?’ ”

She sources her peptides from an L.A.-based company called Centre Research. Its website promises “science backed solutions for medical providers and modern humans alike.” A former Centre employee who asked to stay anonymous explained the company’s process: Customers describe their goals, receive a consultation, and get matched with peptides from a menu of dozens of compounds. “There’s weight loss, body composition, skin and hair, cognitive health,” they said. “There’s one that basically mimics Viagra. And then there’s a few that are, like, mitochondrial, so they just help clean out your system.”

Centre offers peptides for individuals as well as wholesale service for med spas across the country. Its supply comes from a combination of compounding pharmacies in the U.S. and factories in China, according to the former employee. (A representative for Centre said it doesn’t “source any peptides from China or compounding pharmacies. They are manufactured in American facilities.”) It makes a point of testing everything it gets for purity. “We spend thousands of dollars on testing, and we test very frequently,” the former employee told me. Business is good. “Every month is like double what we did the month before, just in our first year,” they said. They described the clientele as an eclectic mix of people. There are the celebrities and “celebrity adjacent” clients in L.A. who “care about aesthetics and stuff.” But many of the clients, especially on the wholesale med-spa side, are conservative people from Middle America.

Like most peptide vendors, Centre operates in a gray area that the former employee compares to decriminalized marijuana: “It’s not illegal, but it’s not, like, approved.” When a client begins using a new peptide, the clinic starts them on a standard dosage and then modulates from there based on their reaction to the treatment. They said everyone makes sure to tell patients, “We’re not medical professionals. If you have any questions or concerns, you need to talk to a doctor.”

The compounding pharmacy that shipped my NAD+ was founded by a man named Brigham Buhler. In September, Buhler made his fourth appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience, where he is a recurring advocate for the peptide movement. On the show, he described a series of increasingly tense meetings he’d had over the past year with the FDA, in which he pushed for compounding pharmacies to be allowed to produce any peptides they want; they’ve been banned from doing so since 2023, after the FDA found the formulas carried “significant safety risks” and lacked proven efficacy.

Buhler believes pharmaceutical companies and their cronies at the FDA want to keep peptides off the table until they can patent and monetize them. “Big pharma got beat to the punch,” he told Rogan. “Compounding pharmacies already have these peptides in their tool belt,” and the FDA doesn’t like that. He told officials that federal restrictions were pushing consumers toward riskier, Chinese-made drugs. “Everywhere you look now, people can buy peptides online with no checks and balances. No FDA inspection, no validation,” he said. “We need to bring peptides back through safe, compliant compounding pharmacies. Not black market, which is springing up everywhere. We’re gonna have another opioid crisis.” If the FDA reverses its guidance, the change may come from the top. In May, on a podcast hosted by biohacker Gary Brecka, RFK Jr. promised to “end the war at FDA” on peptides.

Until then, the safety of what users inject comes down to individual suppliers with little to no oversight. To the rescue: several testing companies aiming to help people safely engage with the gray market. Rina Dukor is the co-founder of a company called BioTools, which makes molecular-testing equipment used by everyone from pharmaceutical giants to federal agencies. Recently, she has been working with a peptide-testing start-up called Finnrick, launched in 2025 by the Silicon Valley entrepreneur Michael Carter. People can send in their peptides and Finnrick will test them for purity and label accuracy. It’s sort of like a for-profit à la carte FDA. “Everyone has a peptide guy,” Carter told the San Francisco Standard. “What people need is transparent information.”

Nearly 30 percent of the peptides tested by Finnrick are either mislabeled, under- or overdosed, or contaminated with toxins or foreign bacteria. “We’ve also seen peptides where it says ‘semaglutide’ and it’s actually Retatrutide or there is no peptide at all,” Dukor told me. She’s particularly concerned about untested products coming from China. Many of the Chinese peptide shipments have COAs, or certificates of authenticity, from testing companies; these are tests showing a given batch of a substance is pure. But the COAs often tell consumers nothing about whether the manufacturer has put the right amount of a substance in a vial. “They might tell you it’s five milligrams. They might put two milligrams. They might put 15 milligrams,” Dukor said. “But it might look the same; it’s just a lot of white powder.” The risks from accidentally taking too much of a peptide can be severe. In July 2025, two women were hospitalized in Las Vegas after injecting peptides at a MAHA-aligned health fair. The manufacturers can also stuff the vials with filler without telling consumers what they are using. Most often, it is a neutral substance called mannitol. But Dukor has seen vials filled with unlabeled glucose, which is dangerous for diabetics.

Adam Katz, 25, blames an overuse of Retatrutide for his necrotizing pancreatitis, a potentially lethal condition.

Photo: Zack Wittman for New York Magazine

Katz, the bodybuilder, is unnerved by what he’s seeing. He said he’s constantly fielding questions from younger people who “want to just use peptides for everything,” he said. Peptides, he warned, “aren’t the answer to everything, and also they’re not harmless.” He has experienced the risks firsthand. After several months of using Retatrutide, he starting having increasingly severe stomach pain until he finally went to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with acute necrotizing pancreatitis, a potentially fatal condition. A month later, in early January, he was back in the hospital with another flare-up. A few weeks ago, I texted Dukor an ad I was served on Instagram for a Chinese company advertising “gray market peptides.” It depicted a huge haphazard warehouse piled high with cardboard boxes. Climate control seemed lacking. “Wow!!!! Crazy is not a sufficient word!!” she texted me. “Peptide structure and thus activity is very sensitive to temperature, pH and humidity.” A peptide can be stored at room temperature, but, she added, “what happens when you send it from China in the summer from Beijing, where it’s humid and hot, and it sits on a trailer for who knows how long on this container, then the container sits in transport again. Is it hot, is it kept in the cold? Who knows!”

She recently caught a glimpse of the peptide boom in China firsthand while giving a talk at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. She noticed testing instruments in a lab were being used incorrectly, giving off-kilter data. She asked the techs whom they were testing for. “They’re like, ‘Oh, the local Chinese peptide company.’ I’m like, ‘What?!’ ” Even if the data they were getting was wrong, she said, “at least they were testing.”

In December, John Ramsay connected me with Jasmine, the sales rep for Xingruida Trade Co. I was curious about the process of buying from abroad — at least, that’s what I told myself. Jasmine sent a detailed document listing dozens of peptides for sale, videos of the factory’s production line, and several testing certificates. I ordered the smallest and cheapest available dose of Retatrutide — ten five-milligram vials — and paid $135 in bitcoin. Two weeks later, the package arrived labeled as PHILIPPINE FACE MASKS and marked for RESEARCH USE ONLY. I sent a vial to Dukor for testing. “It appears to be Reta,” she texted me. “The purity is good.” It was dosed correctly and mixed with mannitol. I opened my fridge and looked at the powder sitting on my shelf next to an onion. What the hell, I thought. Couldn’t hurt to lose a few pounds after the holidays. I reconstituted a vial and shot it into my stomach.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the January 26, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the January 26, 2026, issue of

New York Magazine.