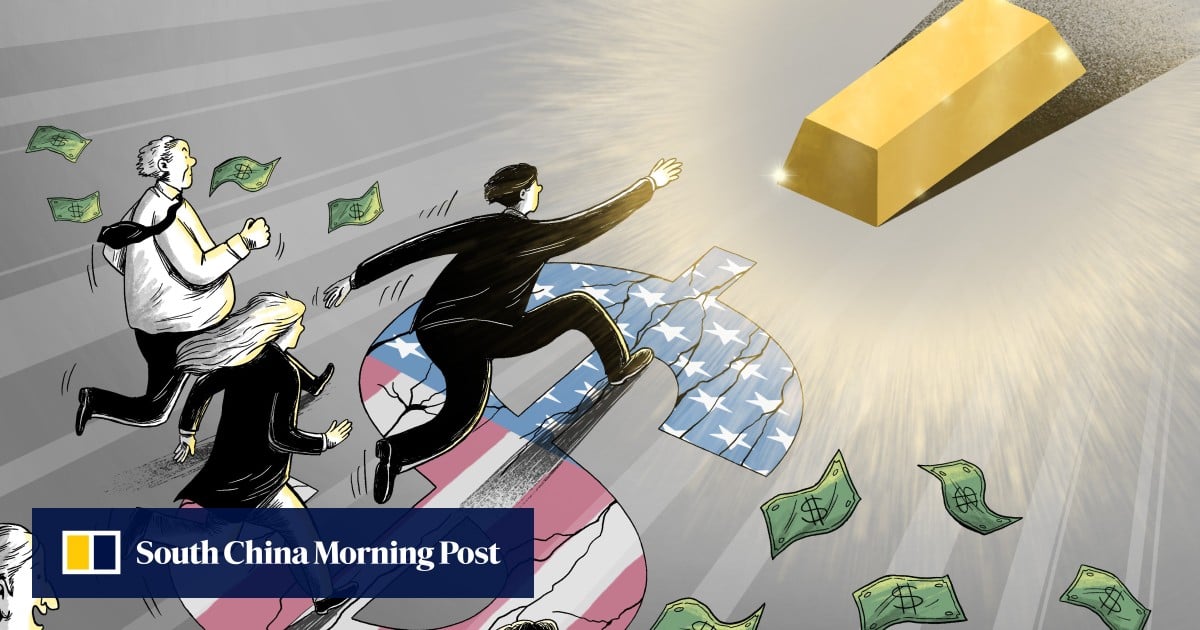

For decades, the US dollar has served as the currency of global reserve, the de facto anchor for the vast majority of international exchanges.

Consequently, United States government debt – most commonly in the form of Treasury assets such as bonds, notes and bills – has long been regarded as a safe haven by investors, prized for its unmatched liquidity and deep market penetration.

That faith has remained strong in the past, even amid global financial crises. But the events of recent weeks suggest that trust could be starting to fray.

Shortly after US President Donald Trump said he would levy double-digit tariffs on eight European countries for their opposition to his threatened seizure of Greenland, a semi-autonomous territory of Denmark, market players have been voting with their feet.

AkademikerPension, a Danish pension fund for educational professionals, announced plans to divest from US Treasuries, and Greenland’s SISA Pension fund is also reportedly weighing a pullback from US assets.

While those withdrawals would represent a drop in an ocean worth trillions of US dollars, analysts said Trump has opened a Pandora’s box. They warned distrust from US allies – compounded by persistent de-dollarisation endeavours by China and some emerging markets – could snowball, eventually straining cross-Atlantic relations and hollowing out the pillars of US financial dominance.

Concerns deepened over the long-term stability of US dollar-backed assets after comments from Trump dismissing worries about the currency’s decline, saying he “could have it go up or down like a yo-yo” on Tuesday. On the same day, the US dollar index – which measures the greenback’s value against a basket of foreign currencies – fell to a four-year low.