A gene duplicated in the evolutionary past has been shown to act as the master switch that determines whether embryos develop as male or female in the African clawed frog.

That finding reveals how evolution can reassign the most sensitive biological decisions without breaking reproduction.

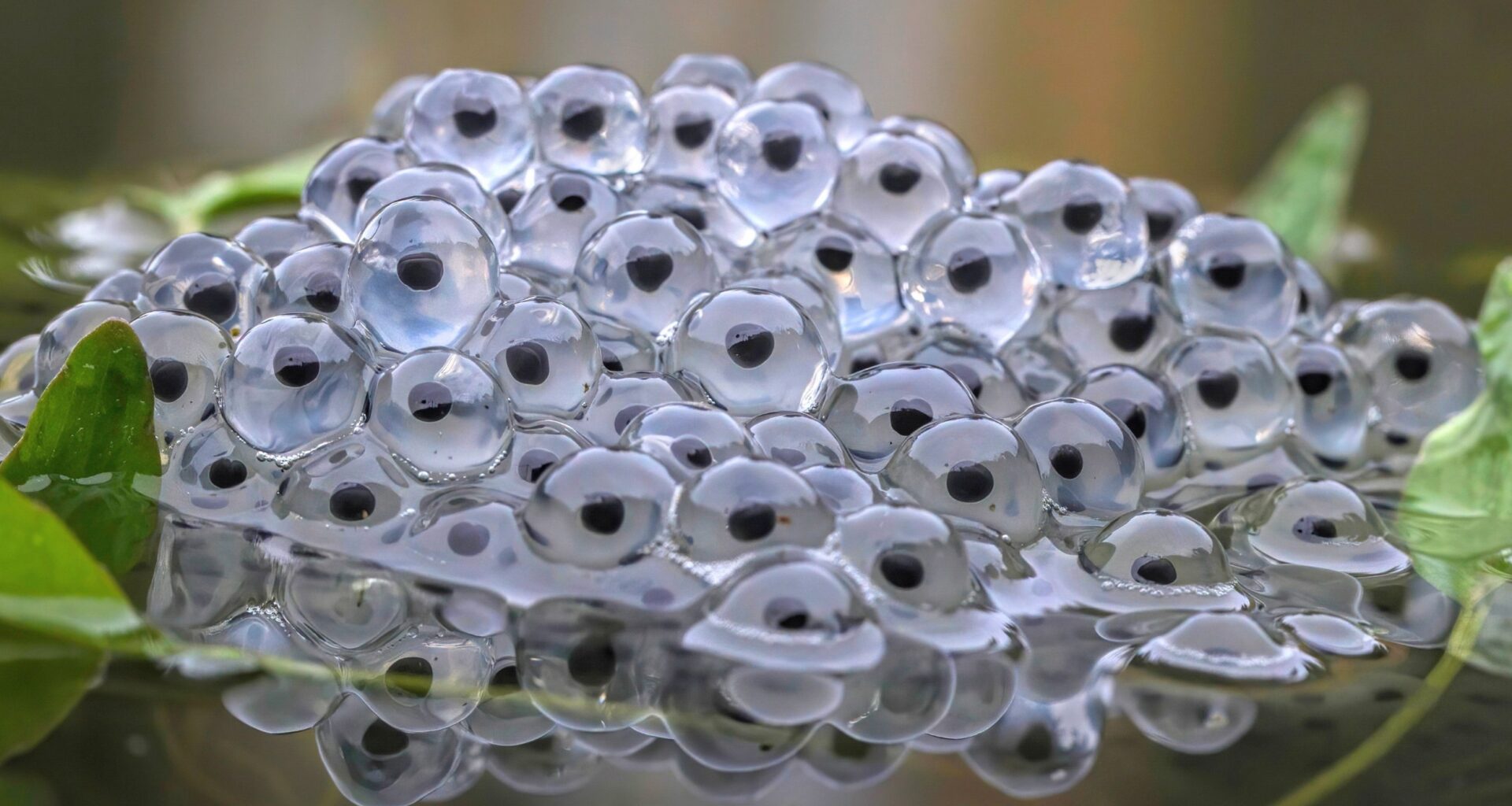

The African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) is a fully aquatic amphibian best known for its flat body, powerful legs, and long history as a laboratory model.

In this species, early development hinges on a gene called dm-w, whose presence redirects the entire sexual pathway toward female formation.

Tracking that shift, evolutionary geneticist Ben Evans documented how this switch emerged while working with long-term frog lines at McMaster University and the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL).

Although distant on a human timescale, the shift occurred roughly 20 million years ago, which counts as recent for a fundamental change in vertebrate development.

The evidence shows that an older sex-regulating gene diverged into separate male and female roles, leaving one copy nonessential and free to take over sex determination.

That handoff marks a boundary where a stable reproductive system tipped into a new configuration, setting up the deeper genetic story that follows.

Female gene blocks males

In these frogs, dm-w, a gene found only in females, pushes the early reproductive organs toward ovaries by blocking male pathways.

Female embryos without dm-w developed as males, so the team treated it as the clearest sign of genetic sex.

The bigger mystery was how a standard gene, shared by both sexes, morphed into a female-only switch.

Answering that required following gene history back before dm-w existed, to a time when frogs carried different genetic baggage.

Genome accidentally duplicated

Roughly 20 million years ago, an ancestor of Xenopus laevis ended up with a doubled genome that copied most genes.

That accident left two working versions of nearly every gene, so one copy could change while the other kept function.

In later generations, some extra copies vanished, but others kept evolving new patterns of activity in different tissues.

Those uneven fates set the stage for sex genes to diverge, because reproduction punishes mistakes more than most traits.

Gene copies diverged differently

After the genome duplication, the frog carried two versions of the same sex-related gene, both inherited from a common ancestor.

Turning those copies off one at a time revealed an uneven outcome that only became clear when the frogs reached adulthood.

Some females appeared healthy from the outside, but inside their bodies, eggs never formed and fat filled the space instead.

“Normally, when you open up a female, you see eggs everywhere,” noted Evans.

A gene copy for healthy sperm

Males told a different story, because the same gene copy turned out to be essential for making healthy sperm.

In a closely related frog species, males remained fertile without the gene, but in Xenopus laevis, fertility collapsed when that copy was removed.

Normal males produced vastly more sperm, while the few sperm left in mutants were misshapen and scarce.

Evolution had quietly reassigned a critical male function to this gene without changing the animal’s outward sex.

Females lost gene dependency

Female frogs revealed an unexpected split, because egg production depended on only one of the two copies.

In the ancestral-like species, removing the gene halted egg formation entirely, but in Xenopus laevis, females managed without one copy.

That pattern shows that one version kept the original role in making eggs, while the other gradually stopped being necessary.

Once a gene copy no longer threatened fertility, it stopped being dangerous to change.

Spare copy evolved freely

With reproduction no longer at risk, the unused copy gained freedom to drift, adapt, and take on new behavior.

Over time, part of that spare copy duplicated again and evolved into dm-w, the gene that now controls sex itself.

“By becoming nonessential, a copy of this gene was able to hijack the entire system,” Evans said.

Such takeovers only work when timing stays precise, because sex decisions must happen early without disrupting later development.

Small changes flip development

Such a takeover marked a genetic tipping point, a threshold where a small change flips development.

Sex determination uses networks of genes, so timing and dose matter, and the strongest signal locks in an ovary or testis.

Small changes in when a gene turns on, or how strongly it turns on, can push that network past a point.

That sensitivity helps explain why sex systems can evolve quickly, but it also explains why evolution rarely experiments blindly.

Relevance to human fertility

In people, the same gene helps keep the testes functioning properly, and disruptions can affect fertility long after development ends.

The frog results show that this gene can behave very differently depending on where and when it acts in the body.

That flexibility helps explain why some fertility genes appear unchanged for long stretches of evolution, then suddenly take on new roles.

Human biology is not frog biology, but the work demonstrates why studying males and females separately can reveal effects that would otherwise stay hidden.

The evidence ties a new sex switch to gene duplication, showing how one copy lost constraints while another picked up new duties.

Following similar changes in other frogs could reveal when such tipping points appear, and when evolution steers away from them.

The study is published in the journal PLOS Genetics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–