A British-led space initiative is offering the public a chance to send their DNA and digital memories to the moon. Called Lunar Mission One, the project combines deep-space science with a unique opportunity for personal legacy, all sealed beneath the lunar surface.

Unveiled in London at the Royal Society, this privately-funded mission aims to drill into the moon’s south pole, deposit time capsules, and raise hundreds of millions through public contributions. Spearheaded by space consultant David Iron, it’s a bold mix of space exploration and digital archiving.

The mission plans to give ordinary people a literal place in space history. For a fee of around £50, individuals will be able to contribute a strand of hair, containing their DNA, alongside a digital archive of their life in photos, videos, music, or writing. The broader aim is to create a long-lasting lunar archive that captures Earth’s cultural and biological record. Iron’s team intends this to be a scientific and personal time capsule, buried up to 20 meters beneath the lunar crust.

Drilling Deeper than Apollo Ever Did

The plan involves landing a robotic spacecraft at the moon’s south pole, where it will drill at least 20 meters below the surface to extract core samples. This depth is unprecedented for lunar missions. As David Iron explained to the Royal Society, “Getting below that top layer of the moon that Apollo looked at should give us extraordinary new data.”

Lunar Mission One – © Lunar Mission One

Lunar Mission One – © Lunar Mission One

Lunar Mission One is collaborating with the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Harwell, UK, a facility known for its work with both NASA and the European Space Agency. According to New Scientist, the scientific part of the mission will span six months, focusing on the analysis of sub-surface materials to better understand the moon’s history and its connection to Earth.

Ian Crawford, the mission’s chief planetary scientist from Birkbeck College, London, emphasized the novelty of the drilling approach: “No lunar or planetary mission of any kind has ever drilled to a significant depth below the surface. The deepest Apollo drill core was only 3 metres long.” He added that the project will allow researchers to measure the geothermal gradient and lunar heatflow for the first time.

A Global Archive Buried in Space

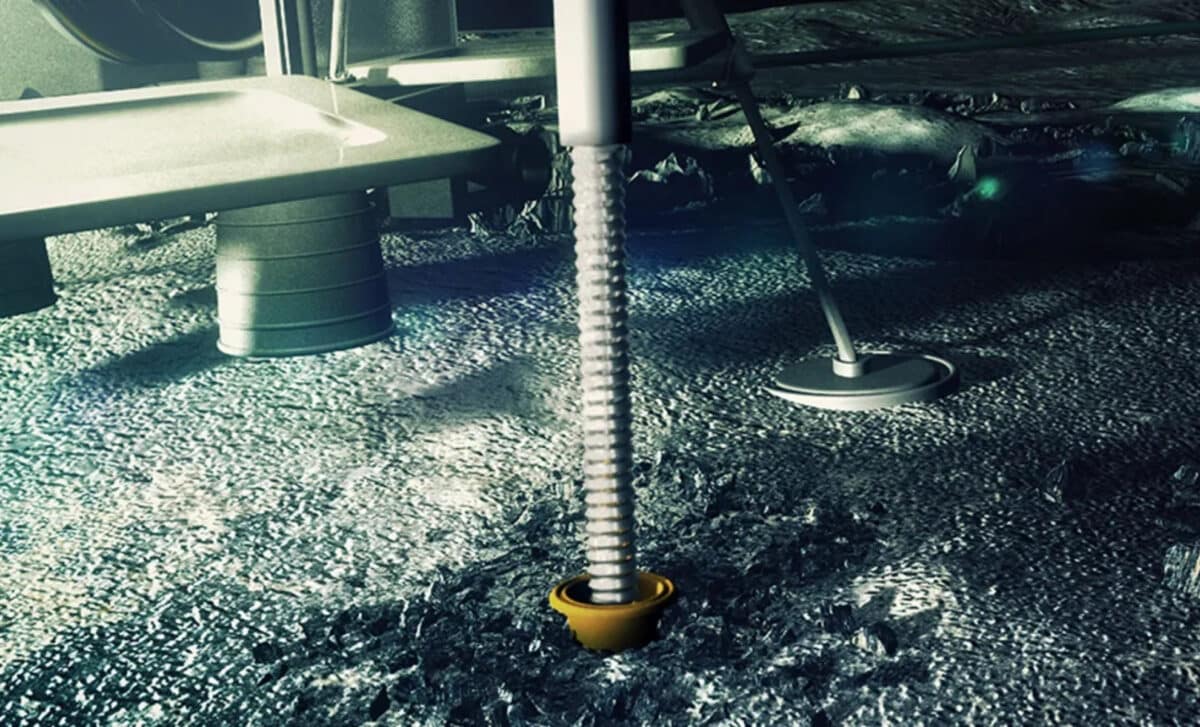

After completing its scientific objectives, the mission will seal yellow time capsules inside the borehole. These will include both a public record, an archive of human civilization, history, and culture, and millions of private entries submitted by individuals.

Once the bore hole has served its science purpose, a series of yellow time capsules will be dropped into the hole before it is sealed – © Lunar Mission One

Once the bore hole has served its science purpose, a series of yellow time capsules will be dropped into the hole before it is sealed – © Lunar Mission One

According to David Iron, the project requires at least 10 million participants to meet its ambitious £500 million funding goal. The first step, however, is a Kickstarter campaign seeking £900,000 to begin design work on the spacecraft. This crowdfunding effort will kickstart the creation of a company dedicated to the mission.

Religious institutions have responded positively to the plan. The Church of England, for instance, confirmed that storing DNA on the moon doesn’t contradict Christian teachings. Iron commented that “It is beyond religion,” framing the archive as a cultural and scientific initiative rather than a spiritual one.

“There’s a Bit of Me up There”

Public reception to the idea has included curiosity and enthusiasm. Roger Launius, a director at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC, described the project as something that “might be a lot of fun.” He added, “The idea of being able to point up at the moon and say ‘there’s a bit of me up there’ will have a lot of appeal.”

Monica Grady, a scientist on the Rosetta comet lander mission at the Open University in Milton Keynes, UK, believes Lunar Mission One could also inspire younger generations. She mentioned that schoolchildren would be invited to contribute to the public archive, calling the idea of a lunar “ark” of digital data “a spark for much discussion.”

Yet, there are technical questions about the viability of storing DNA. Alan Cooper, of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide, warned that hair might not be ideal for long-term storage. He suggested that DNA extracted from cheek cells or blood would be far more stable over time.