![]()

From intimate family stories to documentary and vérité filmmaking that captures life in motion, Myles Matsuno has spent decades turning everyday moments into unforgettable narratives. The photographer discusses the influences that shape his creative vision, the flow states that bring an image to life, and the deeply personal projects that preserve memory and history for generations.

Early Roots and a Childhood Surrounded by Story

Myles Matsuno’s introduction to filmmaking began before he even considered it a career. For him, the camera was an extension of daily life, a way to capture family memories and learn about the world. He grew up in a home where recording life was a constant practice, and the presence of a camera shaped not only what he saw but how he saw it. From a young age, Matsuno was learning to notice moments, understand human behavior, and observe the subtle interactions that tell stories without words.

“The first film I made was in college, but the roots go back to childhood. I grew up with a Hi-8 camcorder always on my sister and me. My dad was constantly recording moments such as sports games, birthdays, school days, and vacations. Stuff like that. Naturally, I gravitated toward the camera and would ask to film sometimes. He would teach me and show me the basics of capturing a moment. As I got older, I did the same thing with my younger brothers and sisters. I loved it,” Matsuno says.

His father’s influence extended far beyond home movies. Working professionally in print and design for film and television, he exposed Matsuno to the craft of visual storytelling from a young age. Watching him prepare marketing materials for major productions, Matsuno learned to analyze shots, consider narrative decisions, and reflect on how images communicate meaning. The combination of early practice and formal exposure to the industry planted the seed of filmmaking deeply in him.

Matsuno Design Group projects.

Matsuno Design Group projects.

“My dad was also in the entertainment industry. In the field of print and design. He was an artist at heart. He owned a company called Matsuno Design Group, which designed one-sheets, billboards, DVD and Blu-Ray box sets for some pretty well-known films and TV Shows. We would watch some of the films he was working on together because he needed to see them before starting on the poster or marketing materials. Then we would talk about shot choices and story. Why a director or cinematographer did this or that. What scenes were memorable in the film. Things like that,” Matsuno says.

“When I look back at my childhood I was very lucky to have a father that instilled storytelling and art in me. That’s where the seed for filmmaking was planted and I have him to give the credit to.”

It was in this environment, filled with observation, discussion, and hands-on practice, that Matsuno’s understanding of storytelling and cinematography began to develop organically. These formative experiences laid the foundation for a career that consistently blends technical skill with emotional resonance,, which he applies to documenting both life’s joys and tragedies.

Vérité, Music, and the Lens as an Extension

Matsuno’s creative voice is inseparable from his approach to seeing. His videography leans toward vérité, privileging spontaneity and the subtle authenticity of human behavior over meticulously staged perfection. Handheld work, medium and close-up framing, and careful lens choices allow him to remain intimate with his subjects while retaining a naturalistic aesthetic. His style is as much about instinct and presence as it is about technical mastery.

“My videography style leans toward vérité. I love handheld work, even in scripted narrative projects, because it keeps things natural and organic. Medium and close-up shots are where I’m most comfortable, and for a long time the lenses I would have on my body 90% of the time was a 50mm and an 85mm lens, which I still reach for today,” Matsuno says.

Music has always been a central influence on his creative process, often serving as the starting point for stories before a camera is even raised. Life experiences, too, inform the emotional perspective he brings to every frame. This interplay between internal vision and external observation creates work that resonates both visually and emotionally, offering audiences an experience that feels intimate and immediate.

“The two biggest influences on my creative process is music and life experiences. A beautiful score or song opens up my imagination and can get me out of a writing or creative block. My first film actually started as a story I saw in my head listening to a song by a band called Port Blue back in the day while on a drive. I had the song on repeat until I fleshed it out in my head. Then I asked to borrow a camera from my university and I recorded to a DV Tape and shot away. No idea what I was really doing. I wish there was YouTube tutorials on that stuff at the time! But I think it really made me learn the editing programs more,” Matsuno says.

As his life and family have grown, his creative lens has shifted. Parenthood and the perspective of lived experience shape not only what stories he chooses to tell, but also how he approaches the people and communities at the center of those stories.

“As I’ve gotten older, my process has shifted a bit. Having two wonderful boys and my beautiful wife in my life changes how I see and tell stories. The way we tell stories shifts just like ones own life. And, as artists, our creativity expands based on our own life experiences, which is just as important as any camera, lens, or technique we may use,” Matsuno says.

Capturing Flow and Being One with the Moment

For Matsuno, the act of capturing an image becomes most meaningful when he reaches a state of complete immersion. In these moments, the mechanics of the camera disappear, leaving only an alignment of perception, intuition, and timing. This sense of flow is rare but powerful, the point at which filmmaking becomes both meditation and lived experience.

“For me, the most rewarding part of capturing an image is when I’m one with the moment. There are times in both photography and cinematography when I’m so locked into what I’m seeing that I forget I’m even hitting record or pressing the shutter button. Even when it may be in a dangerous situation. As a runner myself, it’s the same flow state I feel where you’re one with your body and I’m just moving with whatever is unfolding in front of me. These moments don’t come often for me, but when they do they’re really unforgettable,” Matsuno says.

This philosophy is evident not only in his intimate, vérité-style projects but also in his broader approach to storytelling. Matsuno values patience, observation, and a deep connection to the people and environments he documents, recognizing that authenticity cannot be rushed or forced.

“There are times in both photography and cinematography when I’m so locked into what I’m seeing that I forget I’m even hitting record or pressing the shutter button,” Matsuno says.

These fleeting but intense experiences define the emotional center of his work, setting it apart in a landscape often dominated by spectacle and efficiency. This is especially evident in his work covering the Eaton Fire in Altadena, which stands as California’s fifth deadliest and second most destructive wildfire.

Legacy, Memory, and Preserving Stories

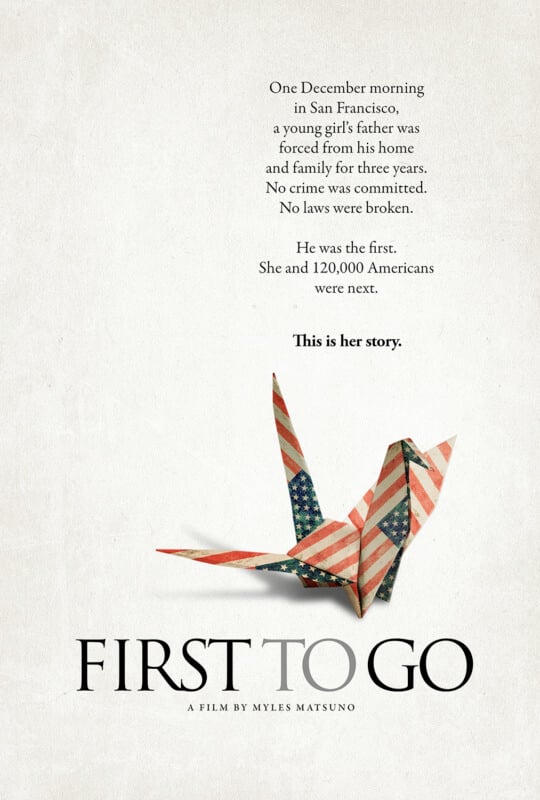

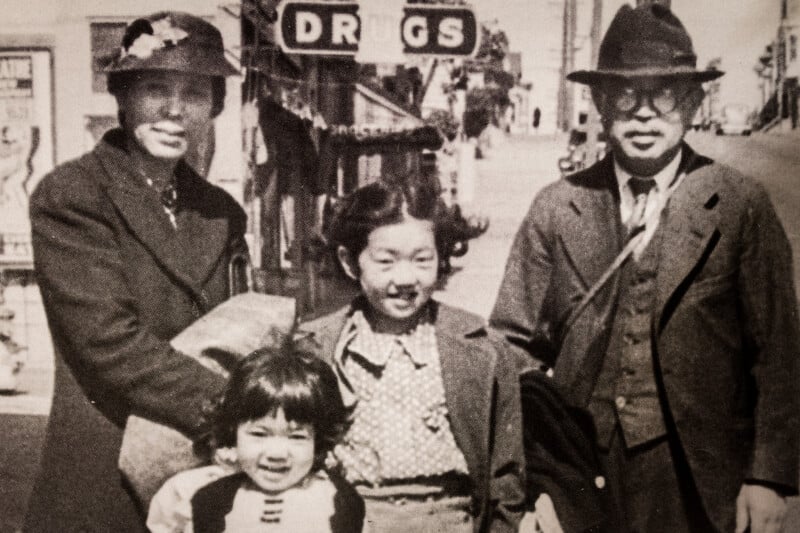

Among Matsuno’s most personal projects is First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family, a film that required meticulous research, deep engagement with family history, and emotional resilience. Digitizing home footage, interviewing relatives, and visiting historical sites were all part of a painstaking process that culminated in a work of both personal and historical significance.

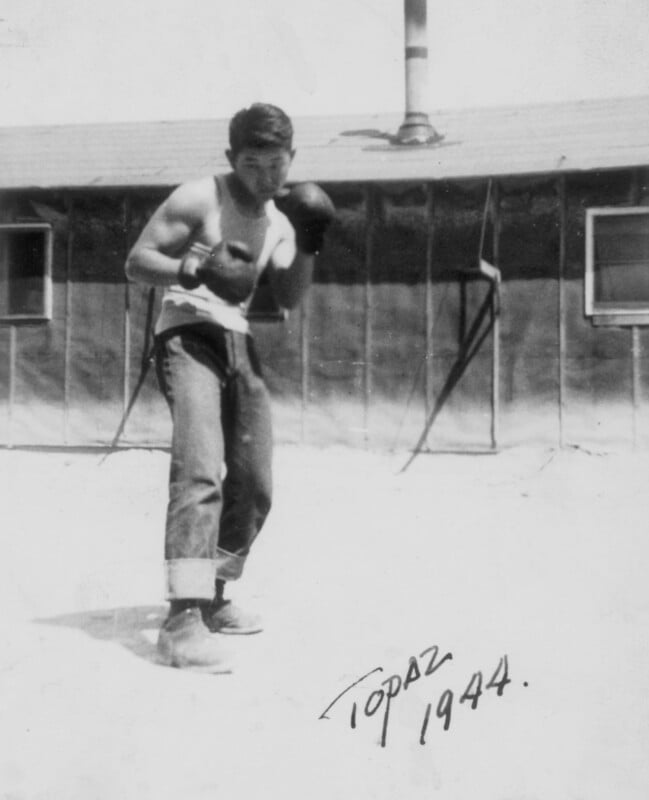

“One of the projects I’m most proud of is my family documentary, First to Go: Story of the Kataoka Family. It took a lot of patience and research to digitize our home footage, visit museums, camp sites, and interviewing my family about their experiences at Topaz, Utah. I even drove up to the Bay Area to meet Dave Tatsuno’s daughter, Arlene, to get her blessing to use her father’s home footage he shot himself in the camps,” Matsuno says.

“Tatsuno was a filmmaker and photographer who documented life in the camp on 8mm, and his film is now recognized as an important part of that history. So to be able to have something like this film and pass it down to my family for generations to come is something I’m extremely grateful for. Especially since a lot of those people in that film are no longer with us, including my own father who passed at the end of 2021,” Matsuno says.

His commitment to preserving memory and telling stories that matter extends beyond family history. Projects like his documentary on the Lee family and Fair Oaks Burger showcase his dedication to capturing resilience, hope, and humanity, ensuring that stories are preserved authentically for those who experienced them and for generations to come.

Looking Forward with Intention

Life experiences, both joyful and challenging, continue to shape Matsuno’s aspirations. From personal loss to the growth of his family or documenting devastating wildfires, every chapter informs his approach to storytelling and his understanding of the impact stories can have on communities.

“Life experiences like losing my dad, building a family, and going through something like the Eaton Fire have really impacted the way I tell stories and my future aspirations with my work. I’d like to continue to help raise awareness and shed light on the stories and people that don’t always get the recognition they deserve. Over the years I’ve seen how authentic storytelling can make a real difference for communities and families going through difficult times, not just from my own work, but from others around the world too. There are people out there doing some really important and wonderful work. You never really truly know what may come from a project,” Matsuno says.

Myles Matsuno’s work reminds us that storytelling is not simply about capturing images or sequences, but about bearing witness. His films, photographs, and documentaries preserve humanity, memory, and resilience, encouraging viewers to see the world with patience, empathy, and presence. In every frame, Matsuno demonstrates that the power of a story lies in its capacity to endure, connect, and inspire, leaving a visual legacy.

Image credits: Myles Matsuno