Feasibility of the toolAcceptability

Regarding acceptability (i.e., how the intended individual recipients react to the intervention (i.e., to the self-assessment process and the tool)), all participating countries obtained a mandate from the hospital management to perform the self-assessment and appointed a hospital-internal coordinator. The assessment team for the individual and the joint assessment (range from seven participants in DE to 24 participants in RS for both individual and joint assessment) was selected and recruited by the hospital-internal coordinator, who had the task of putting together a team in such a way that as many perspectives as possible were covered. The composition of the assessment teams varied across the different hospitals, with teams comprising members from different disciplines and levels within the hospital hierarchy. Not all professional groups were represented in every hospital (Table 2).

Table 2 Participants in individual and joint assessments, and time spent on the assessments

Feedback from the internal coordinators and/or participants within the hospitals indicated that the topic of OHL was considered important, and that people were motivated to engage with the tool. However, concerns were raised about the complexity and length of the tool. In the German hospital a participant suggested that ‘the tool must be shortened so that it is more manageable and does not have a negative impact on the motivation of the participants to complete the self-assessment and indicators must be optimized in terms of content and terminology’ (participant, DE). Furthermore, the full assessment process was perceived to be time-consuming, resulting in some professionals refusing to participate. Yet, with regard to the learning experience on OHL, the joint assessment was considered highly valuable as it provided an opportunity to reflect on organizational practices and identify strengths and areas for improvement in the hospital’s OHL.

Implementation

Regarding implementation (i.e., the extent to which the intervention was fully implemented as planned and proposed), the individual and the joint assessments were conducted according to the protocol in the Austrian, Italian and Serbian hospitals, whereas some adaptations were made in other countries. In the Czech hospital, the joint assessment was conducted according to the protocol, but the individual assessments were not collected prior to the joint assessment and instead presented at the joint assessment meeting followed by a discussion. In the German hospital, individual assessments were conducted according to the study protocol, while for the joint assessment, indicators that were of most interest to the participants (Standards 4, 5 and 6) were selected for discussion. In the Norwegian hospital, the individual assessment was conducted according to the study protocol, except that the clinical staff did not respond to sub-standard 1.1 as the content could be considered most relevant for managers. The joint assessment in the Norwegian hospital was conducted separately for the management and clinical staff groups. In the Serbian hospital, the joint assessment was conducted for managerial capacity, nurses, medical doctors and health associates (i.e., therapeutic staff) in four separate groups. In AT, CZ, and RS, the joint assessments were moderated by the internal coordinator of the hospital and a member of the national research team. In the German and Norwegian hospitals, a member of the national research team moderated the joint assessment. In the Italian hospitals the moderation was done solely by the internal coordinator. The hospitals in AT, DE, NO, and RS held an introductory workshop for the assessment participants prior to the individual assessment in which some background information on the concept of OHL was provided as well as instruction as to how to complete the OHL-Hos.

Practicality

Regarding practicality (i.e., the extent to which the intervention can be delivered when resources, time or commitment are constrained in some way), the tool was considered lengthy and time-consuming to complete. The completion time for the individual assessments ranged from one hour and 45 minutes in the Norwegian hospital to five and a half hours in an Italian hospital. The time for the joint assessments ranged from one hour in the German hospital to six hours in the Czech hospital (Table 2). The tool could be either completed in a Microsoft Word or Excel version. In NO the clinical staff found the Excel format demanding and would prefer a format on a digital platform. One participant said that (s)he would prefer a print-friendly layout of the tool. In AT, where the Word version was used, it was reported by the hospital-internal coordinator that ”50 pages were ’much too long, for management it is unrealistic to fill out such a long survey” (hospital-internal coordinator, AT).

As for the usability of the OHL-Hos, all countries reported that some indicators were repetitive and redundant, and that some were hard to understand due to demanding language and several unknown terms. The glossary and the introductory workshop were highly appreciated (NO, DE). The Czech and the Italian team considered the language of the tool to be clear and comprehensive. Some professional groups in AT, DE, IT, NO, and RS reported that they did not have sufficient knowledge or insight to respond to all indicators. This was especially true for the indicators of Standard 1, which refers to organizational structures and processes that were mostly considered top level management issues. In the Italian hospitals, Standard 8 was considered not relevant in a hospital context because those responsibilities are primarily fulfilled by other services of the National Health System. Some participants (DE, IT, NO) expressed uncertainty about which part of the organization (the entire hospital or individual departments/units) was to be evaluated, as the degree of fulfilment could vary across departments.

Missing or N/A responses were observed for almost all indicators (see supplementary file 2 for indicators with high missing values or N/A responses (≥ 50%) for each participating hospital). For example, half of the participants in the hospitals in AT, DE, IT-B, and RS did not provide responses for whether automated phone systems have a clear option to repeat menu items (indicator 4.1.7). Similarly, indicators related to communication guidelines (indicator 5.1.2a–e) had ≥ 50% missing values or N/A responses in the hospitals in AT, DE, and IT-B. The same was evident in the hospitals in AT, DE, and NO for the indicator about pre-testing digital services (indicator 5.3.3), in the hospitals in AT, IT-A, and IT-B for the indicator about HL interventions for hard-to-reach groups (indicator 8.1.3), and in the hospitals in DE, IT-A, and IT-B for the indicator about public reporting of HL activities (indicator 8.2.1).

Results from the individual assessments were discussed at the joint assessment with the aim of agreeing on strengths and weaknesses concerning OHL either of the organization or of the organizational unit. In Italian, Norwegian and Serbian hospitals, several indicators with different responses from the individual assessments were observed. Experience from the joint assessment showed that different viewpoints were due to the respondents representing different departments and functions. Following discussion, the assessment teams were usually able to reach agreement on the rating of indicators. Therefore, results from the joint assessment partly differed from the individual assessments. In the German hospital it was reported that relevant aspects that were not originally covered in the tool were identified during the joint assessment.

Integration

Regarding integration, (i.e., the level of system change needed to integrate a new process into an existing infrastructure), the internal coordinators within the hospitals and/or participants reported that the tool was suitable for assessing OHL. The tool and the self-assessment process led to awareness and valuable insight when it comes to OHL and stimulated reflections and discussions concerning improving OHL in all hospitals.

IT reported that the joint assessment was also an opportunity for participants to become aware of certain actions already planned within the hospital. The Serbian hospital-internal coordinator reported: ’By filling in the tool and later with the joint assessment, participants became aware of certain problems, but also how they can work to solve those problems. The different opinions of the participants have opened a space for thinking about how to improve work and relationships with patients. It is also important for the hospital to have an insight into its own shortcomings so that they can implement measures for improvement’ (hospital-internal coordinator, RS).

Based on the individual and joint assessments, the Czech project team identified development priorities, which were then submitted to and approved by the hospital management. To maintain the sustainability of the project and to ensure the implementation of proposed interventions, the hospital management decided to formulate an action plan to be implemented within two years. Interventions of the action plan focus on the education of the public and especially children and students (e.g., visits to primary and secondary schools and in the hospital), improving the communication between the hospital staff and patients in the form of audits, training and regular education, launching a patient portal, and more effective transfer of electronic documentation between doctors and providers.

Participants from the Austrian hospital reported that it remained open after the joint assessment who would take responsibility for further actions.

OHL strengths and areas for improvement

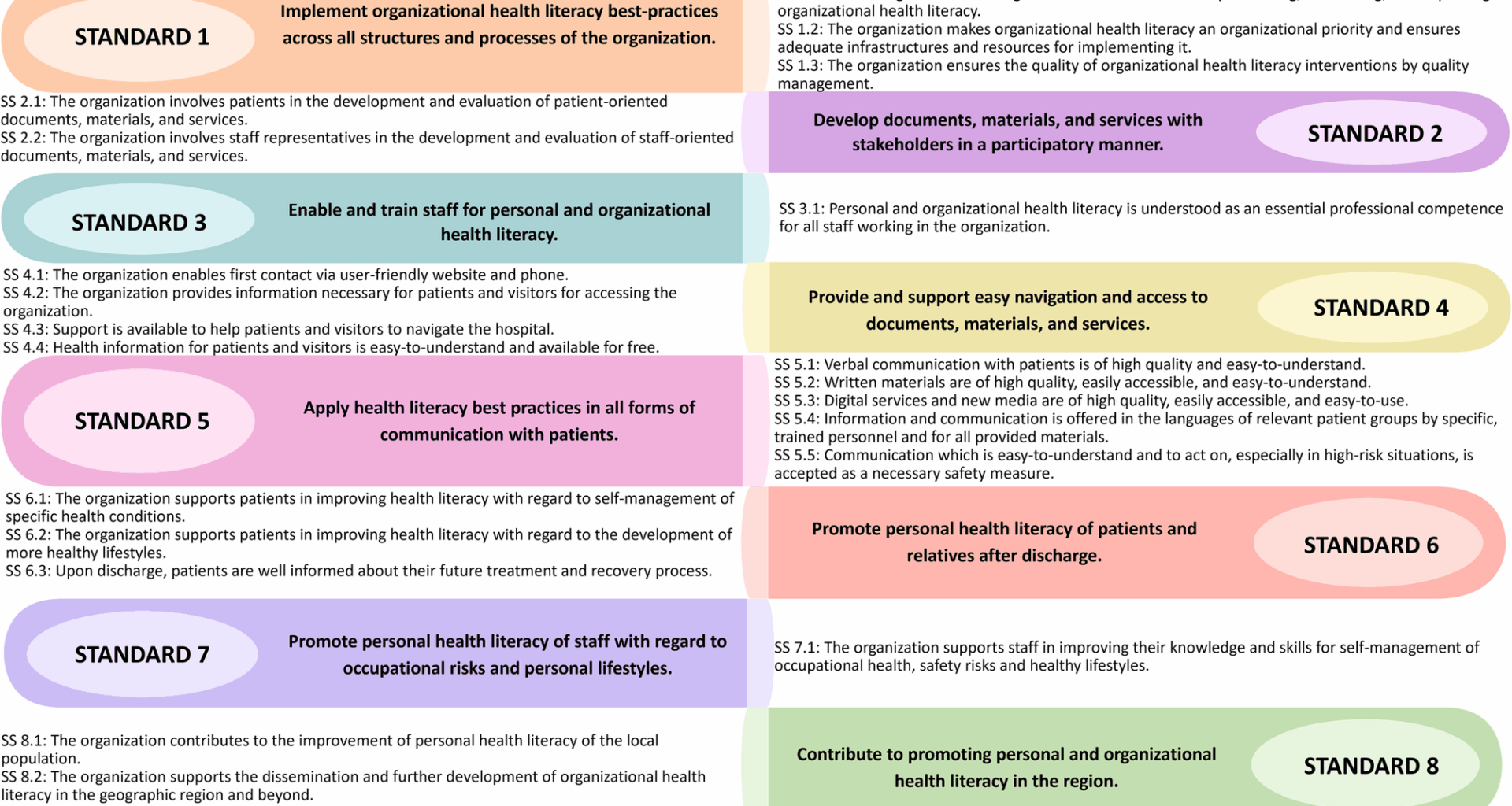

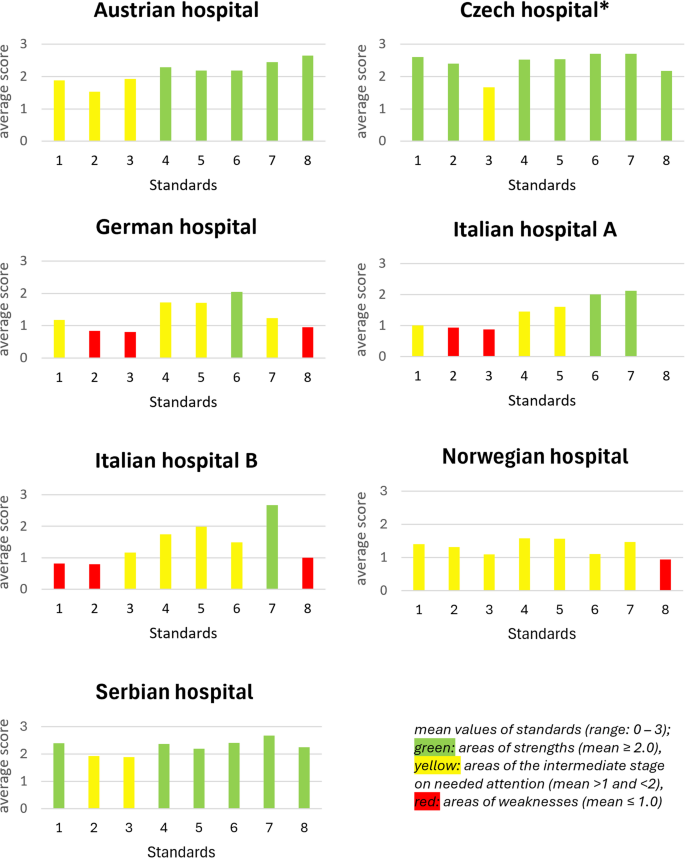

Exploring the OHL strengths and weaknesses, most standards had a high degree of fulfilment in the Czech and Serbian hospitals. Standards 6 (Promote personal HL of patients and relatives after discharge) and 7 (Promote personal HL of staff with regard to occupational risks and personal lifestyles) obtained a high degree of fulfilment in five out of seven hospitals. Low fulfilment was observed for Standards 2 (Develop documents, materials and services with stakeholders in a participatory manner), 3 (Enable and train staff for personal HL and OHL), and 8 (The organization contributes to the improvement of personal HL of the local population) in several hospitals (Fig. 3).

The average degree of fulfilment for Standards 1–8 for each hospital in six countries

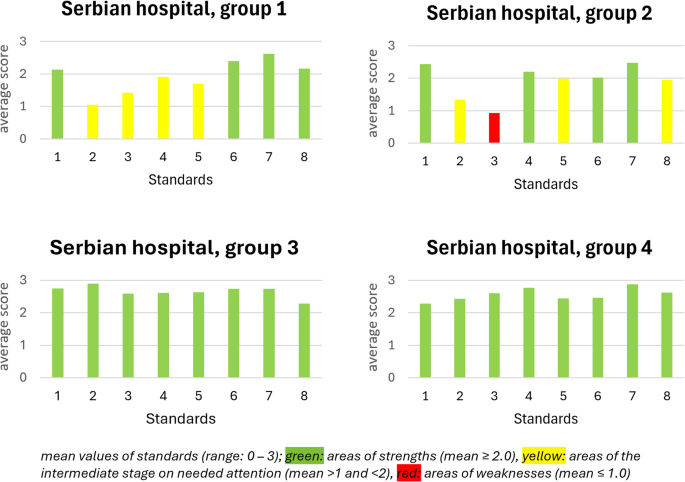

In the Serbian hospital the joint assessment was conducted in four groups. In groups 3 and 4, where the participants were nurses and medical doctors, respectively, all standards obtained a high degree of fulfilment. Other therapeutic professions (group 1) assessed Standards 1, 6, 7, and 8 as highly fulfilled, whereas the others could be considered at the intermediate level (medium fulfillment). The managerial capacities (group 2) identified Standard 3 as an area of weakness (low fulfillment), Standards 2, 5, and 8 at the intermediate level, and Standards 1, 4, 6, and 7 as highly fulfilled (Fig. 4).

The average degree of fulfilment for Standard 1–8 for the Serbian joint assessment groups