Speaking to Winston Churchill in May 1922, the Northern Ireland prime minister James Craig claimed: “The Boundary Commission is at the root of all evil.”

I have chosen Craig’s quote as part of the title of my just-published book on the Boundary Commission as, for me, it encapsulates the importance and fears associated with the commission for the different stakeholders after it became a provision of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Craig and most other Ulster unionists focused their opposition to the treaty on the proposed Boundary Commission.

Although Ulster unionists were not party to the treaty, they were obliged to adhere to its clauses. The commission introduced uncertainty and put Northern Ireland’s future in doubt, at least significant parts of it, yet again.

A Boundary Commission touring party pictured at The Mall, Armagh in December 1924. Left to right, Francis Bernard Bourdillon (secretary), Joseph R Fisher (Northern Ireland representative), Mr Justice Feetham (chairman), Dr Eoin MacNeill (Free State representative), and C Beerstacher (private secretary to Mr Justice Feetham)

A Boundary Commission touring party pictured at The Mall, Armagh in December 1924. Left to right, Francis Bernard Bourdillon (secretary), Joseph R Fisher (Northern Ireland representative), Mr Justice Feetham (chairman), Dr Eoin MacNeill (Free State representative), and C Beerstacher (private secretary to Mr Justice Feetham)

It re-opened the border question, believed settled by Ulster unionists through the Government of Ireland Act 1920 and the establishment of Northern Ireland in the summer of 1921.

Lillian Spender, wife of Northern Ireland cabinet secretary Wilfrid, captured the sense of foreboding and betrayal many unionists felt, particularly towards the Boundary Commission clause (Article 12) of the treaty, believing that “this past week since the publication of the ‘Treaty’ has been the most depressing I have ever known over here. Up to the last I don’t think we ever really believed England would do this thing – would reward murder & treachery & treason & crime of all kinds, & penalise loyalty”.

Her friend, Mrs Erskine told her it was the saddest day of her life: “England doesn’t want us’”.

But even though Craig claimed the Boundary Commission was the “root of all evil” for unionists, it resulted in uniting unionists and leaving the boundary unchanged.

Sir James Craig, the first prime minister of Northern Ireland, described the Boundary Commission as ‘at the root of all evil’. Picture: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images (Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Sir James Craig, the first prime minister of Northern Ireland, described the Boundary Commission as ‘at the root of all evil’. Picture: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images (Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

The seeming threat it represented to the integrity of Northern Ireland greatly strengthened the Ulster Unionist Party, as it adopted its familiar siege mentality to retain the territorial status quo.

British politicians also saw the Boundary Commission clause as an avenue for much evil.

To quote one of the British treaty signatories, Lord Birkenhead, within Article 12 “there lurked the elements of dynamite” to not only cause widespread discord in Ireland, but to wreak “havoc in British affairs” too by bringing the Irish question back to the centre of British politics.

Most British signatories changed their views on Article 12, primarily driven by domestic political concerns within the Conservative Party, from the time they signed the treaty in 1921 to the tripartite agreement in 1925 that shelved the Boundary Commission.

Many went from accepting there could be a significant transfer of territory to insisting the Boundary Commission only envisioned a slight rectification of the border.

For northern nationalists, the prospect of a boundary commission gave false hopes for the transfer of large tracts of territory and people from Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State.

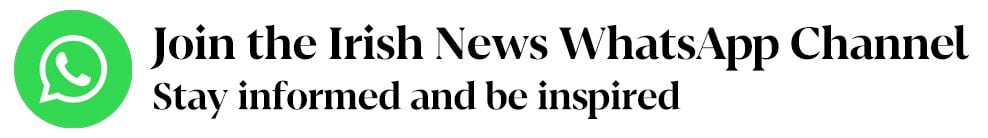

A map showing the Boundary Commission’s proposed changes to the border, including areas marked for transfer to Northern Ireland and to the Free State

A map showing the Boundary Commission’s proposed changes to the border, including areas marked for transfer to Northern Ireland and to the Free State

Nationalists felt they could continue to ignore and obstruct the institutions of Northern Ireland, particularly in areas of nationalist majorities.

The nationalist optimism over the Boundary Commission, in many ways, explains the fraction of time devoted to partition during the acrimonious Dáil Éireann debates over the Treaty.

Both the pro- and anti-Treaty sides supported the Boundary Commission to end or at least limit partition.

The treaty resulted in differing opinions and strategies being adopted by nationalists within Northern Ireland.

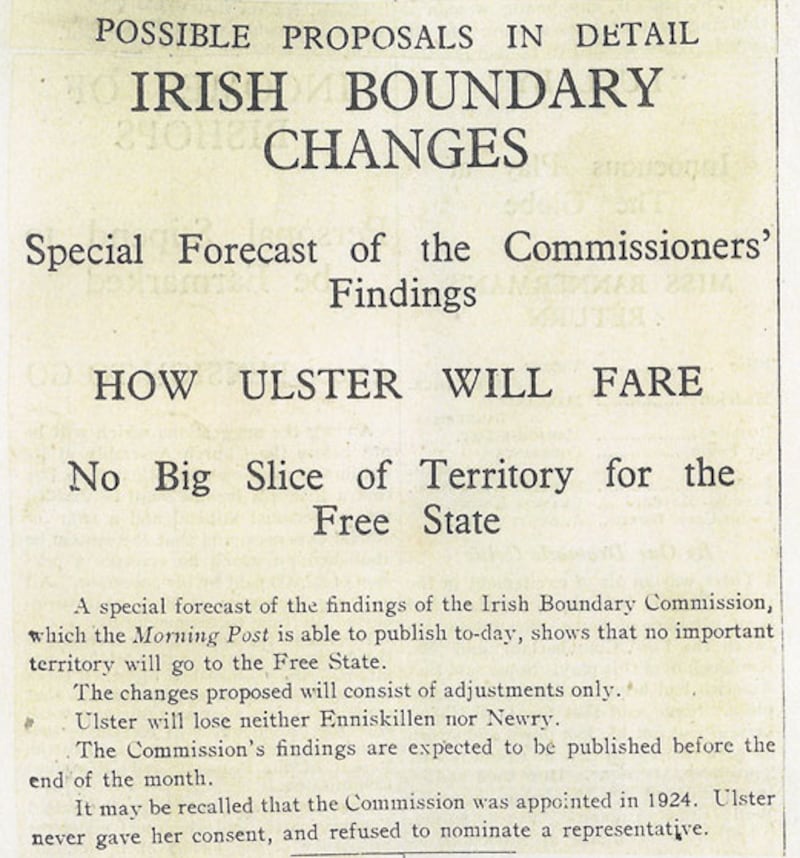

The Morning Post newspaper published details of the Boundary Commission’s recommendations

The Morning Post newspaper published details of the Boundary Commission’s recommendations

Unlike within Ulster unionism, there was a lack of consensus amongst northern nationalists. While local authorities such as Fermanagh County Council and in south Down and south Armagh remained defiant and refused to recognise the Belfast parliament, others such as Tyrone County Council acknowledged its de facto jurisdiction in view of what was described as “the temporary period during which the northern parliament is to function in this area”.

Although unionists viewed the Boundary Commission as a major concession to Sinn Féin, the details and wording of the clause agreed to in the treaty proved to be disastrous for Sinn Féin and particularly for northern nationalists close to the border.

While the Sinn Féin plenipotentiaries were not partitionists and genuinely sought a united Ireland, they blundered enormously in acceding to such a vague and indefinable Boundary Commission, which ultimately was the primary reason for the original border being retained as it was, as it still is.

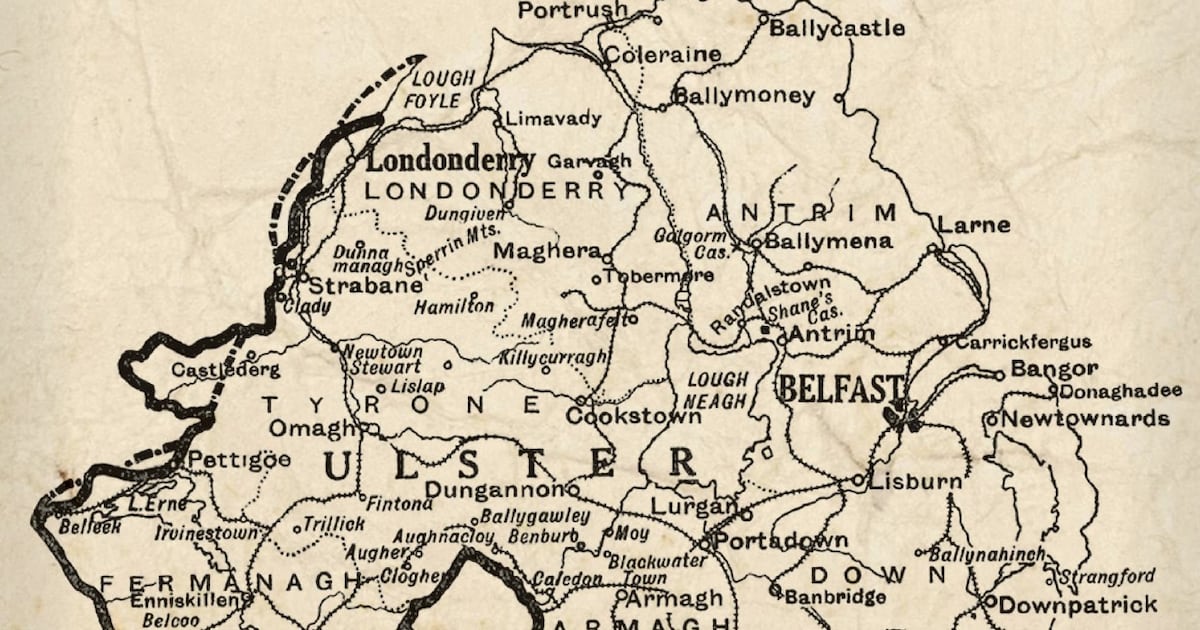

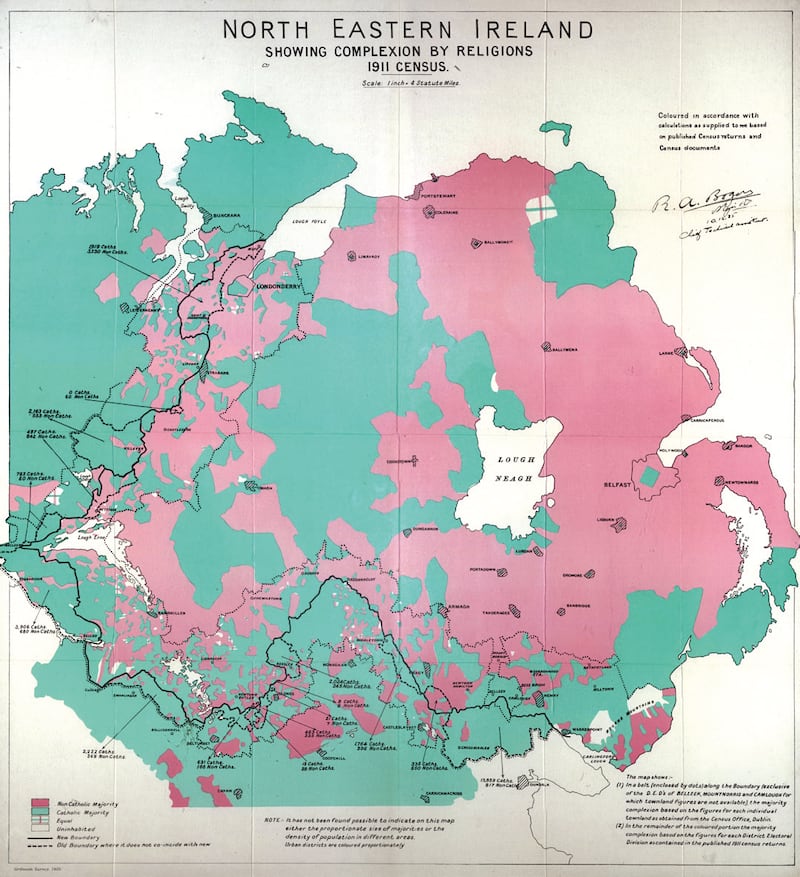

A map produced during deliberations by the Boundary Commission showing religious breakdowns of areas in determining the border

A map produced during deliberations by the Boundary Commission showing religious breakdowns of areas in determining the border

And while it was understandable for most northern nationalists to accept the establishment of a boundary commission under the treaty as a tolerable resolution to the border issue, it was foolhardy and naïve not to scrutinise and tooth-comb its clauses. As it transpired, the devil was in the details.

While James Craig may have been the person who claimed the Boundary Commission was at “the root of all evil” for Ulster unionists, it transpired to be the root of much evil for northern nationalists instead.

It led to false hopes and assumptions that precipitated a catalogue of errors in the months and years ahead that still resonate today.

:: The Root of All Evil: The Irish Boundary Commission (Irish Academic Press) by Cormac Moore is now available to buy.

If you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article and would like to submit a Letter to the Editor to be considered for publication, please click hereLetters to the Editor are invited on any subject. They should be authenticated with a full name, address and a daytime telephone number. Pen names are not allowed.