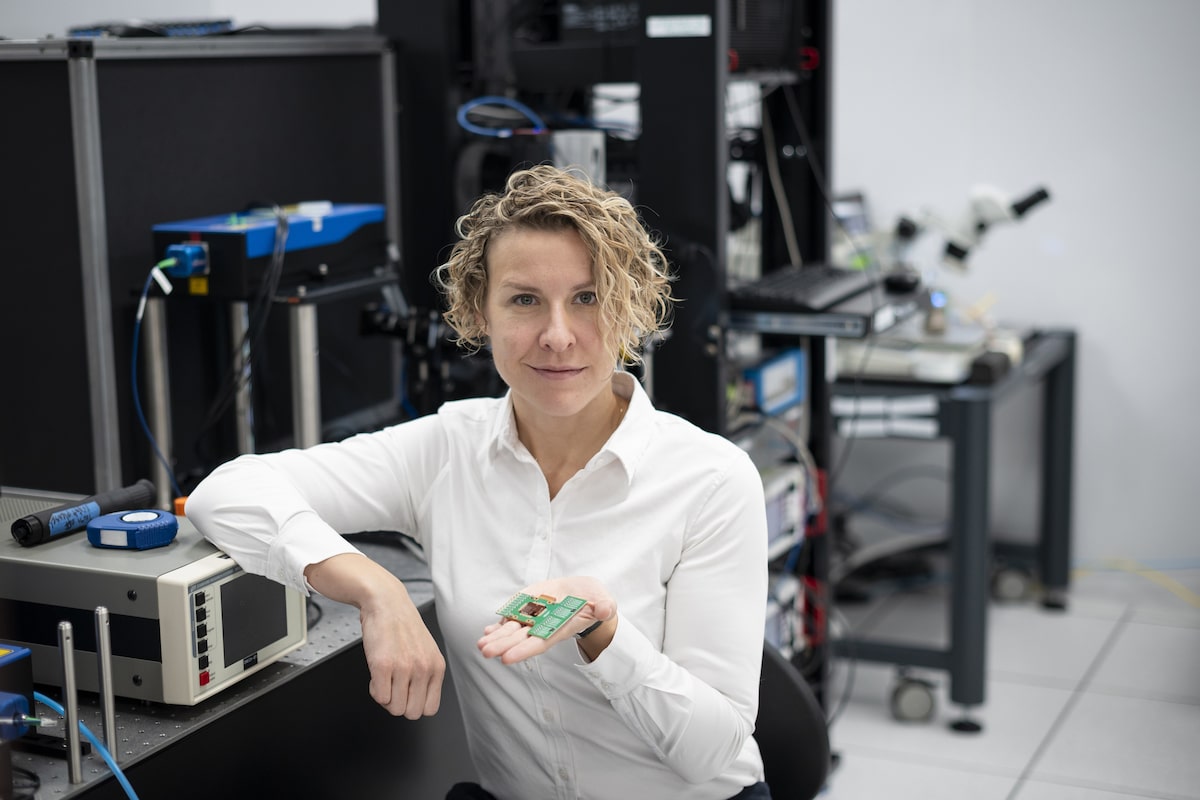

Stephanie Simmons, co-founder and chief quantum officer of Photonic, poses in the company’s Coquitlam, B.C., lab in 2023. Photonic is in the running for more than $300-million in U.S. government funding for quantum computing work, along with two other Canadian companies.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

Three Canadian quantum computer companies are in the running for up to US$316-million apiece in funding from the U.S. government if they can prove within eight years that their machines will work at scale.

The companies – Xanadu Quantum Technologies Inc. of Toronto, Vancouver-based Photonic Inc. and Nord Quantique from Sherbrooke, Que. – are among 18 groups from Canada, the U.S., Britain and Australia that have qualified for the first stage of the Quantum Benchmarking Initiative.

QBI is a novel program launched by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the U.S. government body that funded the creation of GPS and the internet. Others on the list, who qualified after submitting abstracts and giving daylong briefings to DARPA, include HP Inc., International Business Machines Corp. and Rigetti Computing Inc.

QBI is seeking to test claims about how soon quantum computers will become economically and strategically important through a three-stage process. The program kicks off with a six-month stage A that could award participants up to US$1-million by showing their plans to develop industrial-grade quantum computers are plausible.

Those that do move onto stage B, where they’ll have a year to describe a research and development plan to realize their goal. Successful stage B participants could be awarded up to US$15-million.

Finally, in stage C, independent QBI verification and validation teams drawn from U.S. federal labs and leading research institutions, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology, will comprehensively test the technology of the remaining participants to see if it works.

This is where the real money is: DARPA says it could pay up to US$300-million to each group that succeeds, though payments cannot exceed 50 per cent of their research and development costs. That implies companies will need to raise substantial matching capital.

“QBI is not meant to choose a winner and fund your research and development plan,” said Dr. Joe Altepeter, QBI’s program manager. Rather, the program is structured to reward only those that can quickly execute against their roadmaps and deliver something useful.

However, making it through will likely anoint a winner or winners in the global race to develop a working quantum computer.

Xanadu founder Christian Weedbrook, right, in the company’s office in 2019.Tijana Martin/The Globe and Mail

“I can’t think of any other program that has generated this much excitement and interest from startups and big companies – and a lot of investors know about it,” said Christian Weedbrook, Xanadu’s founder and chief executive officer.

Quantum computer developers have collectively raised and spent billions of dollars so far, and QBI will likely influence financiers in determining who to continue backing.

Conversely, groups “that don’t get in will be challenged to raise venture capital,” said Ray Laflamme, co-chair of the federal Quantum Advisory Council. The council has recommended the Canadian government provide matching funds to any domestic company that makes it through QBI.

Council co-chair Stephanie Simmons, who is also the co-founder and chief quantum officer of Photonic, said the U.S. government will gain access to “deep knowledge that other governments won’t have” through QBI.

“That will give them geopolitical and other advantages that are important in the upcoming economy.” Creating a matching program here would mean “this information will also be owned by the Canadian government.”

A section of the ‘Borealis’ quantum computer developed by Xanadu pictured in 2022. The tech world has been caught up in debate over how soon the technology will deliver on its potential to outperform other computers.Galit Rodan/The Globe and Mail

Proponents of quantum computing have long theorized that machines that can draw on the sometimes bizarre physical properties of matter and light at atomic scales will someday vastly outperform the world’s most powerful supercomputers at certain tasks.

Such machines would perform calculations that would take millennia for existing machines to solve, with applications in areas such as financial modelling, optimization planning, cybersecurity, and discovery of advanced materials and pharmaceuticals.

From the archives: Canadian company Xanadu tests building blocks for commercial quantum computer

Skeptics point to the significant technical barriers that must be surmounted before this can happen and suggest a viable industry may be decades away.

A debate over how near the technology is to delivering on its potential has roiled the tech world, particularly after investors piled in last year to stocks of several quantum developers – including Canada’s D-Wave Quantum Inc.

Earlier this year, Nvidia Corp. chief executive officer Jensen Huang said he didn’t expect quantum computers to become “very useful” for 15 to 20 years, sparking a selloff in quantum stocks – though he backtracked last month, saying he’d been wrong.

Mr. Altepeter said that among the 10 smartest physicists he knows, “half are convinced this will be the most important technology of the 21st century and will revolutionize everything we do. The other five are convinced you’ll never build a quantum computer no matter what you do” – or that if one is built, “it would never be more useful than your laptop for solving a real problem.”

Dr. Simmons said that in the 1930s, physicists believed “nuclear reactions were impossible. They changed their thinking and unlocked everything in six years. Commercializing a branch of physics looks hard until it doesn’t.”

Large tech companies and startups alike have championed different approaches to the technology, down to its most basic constituents: the quantum bits, or qubits, used to perform calculations.

In recent months, developers have notched a series of advances that demonstrate the selling points of these pathways. Many have focused on a key challenge: quantum computers are highly prone to error, a problem that becomes more pronounced as systems scale up to a point where they are commercially relevant.

Progress in error correction featured prominently last December when Google unveiled its latest quantum chip, called Willow. In February, Photonic published a new approach to error correction it said will require fewer qubits.

Days later, Microsoft garnered attention – and pushback – with a claim that it had developed a “topological qubit,” which the company said could lead to more fault-tolerant systems. And in March, Nvidia unveiled its plans to open a research lab in Boston whose focus will include quantum error correction.

Dr. Altepeter said QBI was borne from skepticism at DARPA about quantum computing, including his own. But DARPA’s mission “is to prevent and create strategic surprise” for the U.S. government, he added – enabling it to anticipate technological breakthroughs that could undermine the country or create them to the U.S.’s advantage.

Just because Dr. Altepeter and his colleagues are skeptical, “that doesn’t mean we don’t want to go look” into what developers are up to, and the rich potential award was meant to draw many participants into the program, which he said has happened.

“I would love to be surprised. If companies make it through that gauntlet, we’re really willing to advocate for them inside the U.S. government in rooms that they can’t go to and say, ‘Look, we did our best to show this doesn’t work, these guys made it, they can really build this thing,‘” he said, adding that the program was designed to be a “simple, cheap way” to determine that.

Mr. Laflamme agreed that QBI “is a very smart way for the U.S. to keep at the front. By doing this, the U.S. will know who has the lead in the world and where people are, everywhere.”

QBI evolved out of an earlier quantum-funding initiative at DARPA that is assessing efforts by Microsoft Corp. and PsiQuantum. Dr. Simmons asked whether QBI could be hit by Elon Musk’s government DOGE cost-cutting initiative, said she would be “quite surprised” given the strategic priority of quantum computing, though she added “it’s an unpredictable world.”

Dr. Altepeter said “there is always a danger there’s going to be something more compelling to spend the government’s money on. If it’s the most valuable thing people can spend taxpayer dollars on, we are going to be ready to do a fantastic job and change the world.”

And if nobody makes it through, “then we will pat ourselves on the back for a job well done for having done the evaluation and we will send whatever money we got back to the treasury.”