The rise in costs and demand for care means less cash left over for services like bins and libraries A review of council services is planned(Image: Getty)

A review of council services is planned(Image: Getty)

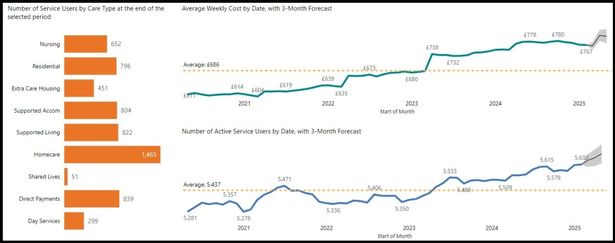

A City Hall boss urged MPs to overhaul social care as almost half the council’s day-to-day budget is spent on around one per cent of Bristol’s population. Bristol City Council is now planning a raft of changes to care for over 5,000 elderly and disabled people to keep costs under control.

Both costs and demand for support are rising, and outpacing the extra income from raising council tax by the maximum amount allowed. This means there is less money to spend on other day-to-day services, such as collecting bins or fixing potholes.

Hugh Evans, executive director of adults and communities, updated councillors on the adult social care committee on Monday, May 12, about the crisis. He also gave evidence to a select committee in Westminster, which warned of the wider impact on services like libraries and youth clubs.

There are 5,585 adults in Bristol receiving care paid for by the council. Adult social care takes up 46 per cent of the council’s day-to-day spending, not including areas like schools or transport upgrades. Across the country, an increasing chunk of council budgets are taken up by paying for care.

The council is now planning to invest £2.7 million on transforming the social care department. This will help reach the target of saving £14.3 million from the budget, by improving services and reducing ongoing costs. Over £200 million is planned to be spent on caring for people this year. Quite a lot of this money is used to pay companies and charities to provide care for people.

An update on the plans was given to councillors on the adult social care policy committee on Monday, May 12. They involve providing support “as early as possible”, which would avoid people’s health worsening and their care needs growing. Another factor is reducing the costs the council pays to care firms, which can sometimes charge “more than they deserve”.

Mr Evans said: “We need to ensure that we buy care at a fair price, so that we don’t pay too much for care from overenthusiastic providers who are trying to take more money from us than perhaps they deserve, that isn’t a fair cost of care.”

Encouraging the local care market to grow also features in the plans. This would reduce costs on sending people far away to receive care, while also improving their experiences of care too. Mr Evans added: “We’ve failed if we have to send someone to another part of the country to receive a high level service.”

Both costs and demand for care packages are increasing(Image: Bristol City Council)

Both costs and demand for care packages are increasing(Image: Bristol City Council)

The care department will explore using artificial intelligence, to save “hours and hours of people writing stuff up”, such as transcribing minutes from meetings. Specialist supported housing is planned for people with complex care needs, which Mr Evans said was “nationally innovative”, saving money on high-cost placements in care homes.

The department will carry out a “strategic review” of care services the council provides itself. These include Shared Lives, a scheme where carers live in the home of service users; reablement services; the Redfield Lodge care home; community meals; and Bristol Community Links, two day centres in Southmead and Knowle.

Sometimes people asking the council for support have to “repeat their story again and again”, as staff ask for the same information several times due to “convoluted team structures”, according to Samantha Graves, who is managing the transformation programme. Because of this, bosses will redesign how the department operates when receiving requests for care.

Another issue across the country is growing levels of unpaid debt, which people owe councils. In Bristol, the council recently hired a new finance director, who “has got the bit between his teeth when it comes to the debt agenda”, according to Mr Evans. In the care department, some people receiving support have to contribute towards its costs, and get sent a bill by the council.

Risks facing the plan to make budget savings include the recent increase in minimum wage, which will impact small care businesses and raise costs for councils, and a reorganisation of the NHS, which councils work closely with to provide health and care needs. The government has set up a commission on how to reform social care, and the results will be published in 2028.

Speaking to MPs on the health and social care select committee in March, Mr Evans urged a rethink in how councils are funded. Rising council tax by the legal maximum amount does not cover the increasing cost of providing care, which legally the council must do. This leaves other services suffering.

He said: “The majority of people do not have a learning disabled or physically disabled family member. Four out of five people do not need recourse to adult social care in their older years. Social services are not really a major factor in those people’s lives.

“Potholes, bins, parks and things like that are more important to them. It is a big argument to win that social services should take more money from overall budgets.”

A report published by the select committee earlier in May called on the government to act urgently on reforming social care. This could include reducing the financial demand on councils.

The report said: “The cost of this vital public service continues to increase, with £32 billion spent on adult social care in 2023/24, and an unsustainable pressure is falling on local authorities. Without reform we will all keep paying a high price for a failing system.

“The increasingly high proportion of spending on adult social care is crowding out spending on other services, such as fixing potholes, keeping libraries open and providing youth services, forcing many to provide only the bare minimum to residents. It is also preventing councils from reducing future demand for adult social care through investment in prevention activities.

“There is a growing disconnect between what is paid for and what residents expect to be delivered, risking an erosion of faith in democracy. There needs to be a more open public conversation about what is driving a reduction in council services, and how adult social care contributes to that.”