The terrible thoughts in my head had been building for some time, but it was on Tuesday morning that they peaked.

My husband had left for work, my daughter for school and I was alone in the house when my brain began to go to war on me.

What if I had done something awful to someone on the Tube the evening before and blanked it out because I was secretly a psychopath? Had I accidentally sent my child to school with a water bottle full of bleach? Had I emailed a terrible, abusive message to her teacher and deleted it from my sent items to hide the evidence?

On and on the intrusive thoughts came, many of them too awful to repeat here.

Instinctively, I crawled under the duvet, as if this could somehow shut them out. But it couldn’t, of course. A lifetime of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) has taught me that wherever I go, I have to take my head with me and I can never predict when it’s going to throw thoughts like this at me.

I first suffered from this most misunderstood of mental illnesses when I was a child and believed I was dying of AIDS. I washed my hands until they bled, was scared to leave the house, convinced myself I might hurt my family simply by existing. Later, I began to chant phrases under my breath, in the hope this would keep them alive.

I had a series of so-called ‘happy’ words I would say to myself again and again in an attempt to ‘neutralise’ the terrible thoughts that seemed to appear unbidden in my head.

My brain tormented me, endlessly. What if I was a serial-killing paedophile who had somehow forgotten their terrible crimes because they were so evil their brain simply couldn’t keep them there? I was the worst person in the world, an aberration, or so the OCD told me. My life has been spent in an almost constant state of fear – the compulsions that I developed to try to dampen the obsessions only made them far, far worse.

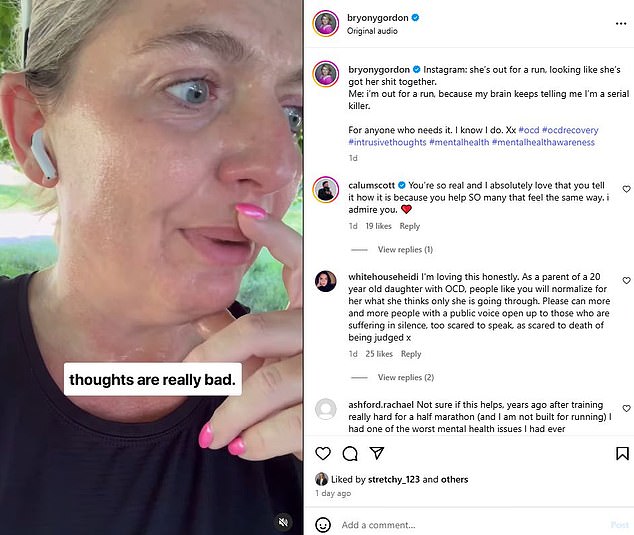

I threw on my running gear, legged it out the door and – five kilometres later – found myself making an impromptu video about this nasty little episode of OCD

No filters, no edits, just me, sweaty and teary and needing to connect with other people who know what it’s like to have this horrible illness

When you have OCD, your baseline feeling is terror and somehow you begin to normalise it. You mask it, to make other people comfortable. At first I did this by numbing the fear with alcohol and drugs, but that in itself brings its own problems (alcoholism and addiction).

Since I got sober almost eight years ago, I have been lucky enough to get a lot of therapy and now the gaps between episodes of OCD have become wider and wider, my nervous system no longer under constant attack. I experience it every few years, as opposed to every few weeks.

But when it does sneak up on me I can feel every bit as defenceless as I did when I was 12. As anyone with OCD knows – people with real OCD, as opposed to those who use it as a byword for being a bit clean and organised – the illness exerts a vice-like grip on your brain, from which it can feel impossible to escape. It can strike when I’m feeling low and when I’m feeling high: I’ve learnt that I have a tendency to punish myself when things are going well.

But I’ve also learnt a few tricks in my time. I know I have to get outside, even if only briefly, and I know I have to call the illness out. Which is why, on Tuesday, I threw on my running gear, legged it out the door and – five kilometres later – found myself making an impromptu video about this nasty little episode of OCD.

Then I uploaded it to Instagram. No filters, no edits, just me, sweaty and teary and needing to connect with other people who know what it’s like to have this horrible illness.

I also felt compelled to inject some reality into the endlessly glossy social media landscape, where celebrities and influencers have co-opted Mental Health Awareness Week (which happens to be this week) to promote their various wellbeing products.

As I watched yet another star discussing the importance of self care for their mental health, I wanted to scream: ‘I know I’m supposed to look after myself, but it’s bloody hard when two thirds of my own brain wishes me dead!’

The response to my post was immediate and overwhelming. Hundreds of messages flooded in from people who needed to feel less alone about the apparent madness of their brain. And as the day wore on and I read more and more of the kind, brave messages in my inbox, I was reminded of how much work still needs to be done when it comes to mental health… or, more specifically, mental illness.

I have been campaigning in this sector for more than a decade and have seen how we have moved away from talking about the more life-limiting conditions – psychosis, eating disorders, major depressive incidents – in favour of discussing things such as feelings and self-care.

And while there is nothing wrong with discussing feelings or self-care, we must make sure it doesn’t come at the expense of the more difficult conditions, the ones that ruin lives and cannot be cured simply by lighting a candle and running a relaxing bath.

I am lucky. I can afford a private therapist. I have resources and support around me to keep me ‘high-functioning’, so that I can still go for a run and write this column. But I know, from the messages I received this week, that there are plenty of people who don’t have such luxuries, who have no idea where to turn as they try to navigate their way out of a crisis.

I know from reports this week that many distressed mental health patients seeking urgent help have to wait in A&E for up to three days at a time, watched over by security guards, rather than nurses. I know that despite government promises of investment, the mental health system in this country is beyond breaking point, with many of the people working in it struggling themselves to stay afloat.

And this is why I continue to bang on about the darkest bits of my brain, long after it ceased to be fashionable. Because a society which ignores the grim realities of mental illness has no chance of ever being truly healthy.

Kim puts couture into the courtroom

Kim Kardashian, accompanied by Kris Jenner, leaves the courthouse in Paris

Forget the Cannes red carpet – the place for style-spotting this week is the Paris court where Kim Kardashian has been giving evidence during the trial of ten people accused of robbing her in 2016. You’ve got to admire her for taking to the stand wearing a vintage John Galliano blazer dress, Saint Laurent heels and lashings of diamonds. Proof that the Kardashians even put the couture into the courtroom.

That post was poor form, Gary

Gary Lineker at the Action for Children Ultimate News Quiz in March this year

Gary Lineker is in hot water again, this time for re-sharing an Instagram post about Zionism that included an antisemitic emoji.

He quickly deleted the post and apologised, but in the digital world, especially one where you’ve got 1.2million followers, everything is seen. What is it about social media that robs so many otherwise intelligent people of all common sense? As Lineker himself might say: poor form.

The latest social media craze is checking for a ‘millennial mole’ – a small coloured spot on your left forearm, to be precise. A spooky amount of people born in the 80s and 90s apparently have the mark, though what it means nobody knows. ‘What a load of rubbish!’ I thought, before looking down to see… yep, a millennial mole.

Vinted’s such a faff, Becky!

Rebekah Vardy enjoying some sun at the beach

Becky Vardy has caught the Vinted bug, putting loads of old swimwear and children’s clothes onto the reselling site. I too had a phase of clearing out my cupboards and putting everything on Vinted, but it was short lived. I couldn’t cope with people trying to haggle down frocks from £5 to £4.50, or the endless trips to parcel drop-off points in the middle of nowhere. I give it a few weeks before Vardy caves like me, and takes the lot to the charity shop.