It restored his movement and his confidence Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

When Bill Bridger first noticed the tell-tale signs, he was working as a consultant trainer for the police. In the middle of presentations, a slight tremor in his right arm would betray him, subtly at first. His foot began to drag.

These weren’t mere signs of fatigue or age. They were the early warnings of a life-altering diagnosis that would arrive four years later, in 2015: Parkinson’s disease.

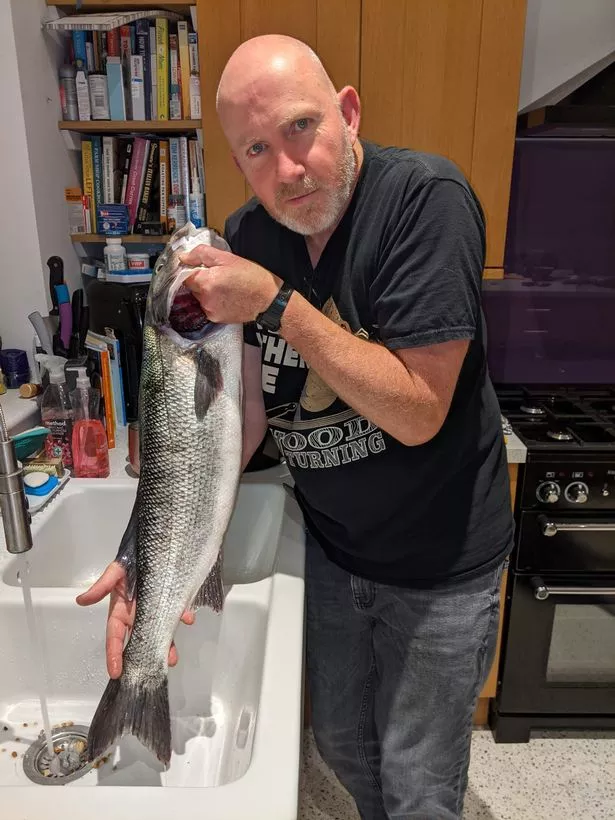

“At the time, I was incredibly active,” Bill recalls. “Cycling, running, fishing, camping—you name it. I was always outdoors. I’ve never been someone who sits in front of the telly all day.” But gradually, those activities began slipping through his fingers.

The diagnosis came when he was just 43 years old. For many, Parkinson’s conjures images of older adults, but Bill’s case was a stark reminder that the condition does not discriminate by age.

The tremors, the stiffness, the gradual loss of physical autonomy—these began to intrude on every corner of his life. Professionally, he was forced to switch jobs. Personally, the toll was heavier still.

“The biggest thing it took was confidence,” Bill shares. As his condition progressed, his world began to shrink. “I stopped trying new things. I froze in place. I had constant dystonia, tremors, balance problems. Even walking around the house was unsafe.”

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

With the body failing, the mind doesn’t remain untouched. Anxiety crept in, filling the spaces where freedom used to live. And while Bill was the one diagnosed, the disease cast a wider net—reaching his wife Ally, who became his primary caregiver.

“She lost all her free time. She helped me dress in the morning and again after work. She drove everywhere. Eventually, she had to push me in a wheelchair.”

But what cut deeper was the social invisibility she endured. “We’d be at a pub and friends would ask me, ‘How are you, Bill?’ Then turn to Ally and ask, ‘How’s Bill doing?’ Rarely did anyone ask how she was. It’s like carers become invisible.”

This part of the experience, Bill says, was one of the most upsetting.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) had been on Bill’s radar almost from the start. His NHS consultant had floated the idea early on, but like many, he harboured reservations. After all, the thought of brain surgery isn’t something anyone rushes into lightly.

But by the time seven and a half years had passed, Bill had reached a breaking point. “I was only getting 15 minutes of relief in a three-hour medication cycle. I saw my neurologist and said, ‘Please, for God’s sake, let me have this operation.’”

What followed was, in his own words, “really smooth.” The surgery, conducted at Southmead Hospital in Bristol, implanted electrodes deep in his brain, connected to a pulse generator designed to regulate abnormal brain activity.

The transformation began almost immediately.

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

“Once I was switched on post-DBS, the difference was incredible. Nearly all my symptoms were drastically reduced or completely gone. My quality of life went from a 2 to a 9 out of 10.”

From struggling to lift a cup to making coffee unaided, Bill’s daily capabilities surged. The simplest actions became triumphs. “I can now walk, move, even enjoy simple things like rubbing my eye — something I couldn’t do before without help.”

There’s a particular memory Bill returns to when trying to explain just how life-changing DBS was.

“The day after I was switched on, I was staying at a friend’s house. Their son was getting married that day. I didn’t think I’d be able to attend, having just had the procedure. But that morning, I slept nine hours—for the first time in nearly ten years.”

He didn’t need help that morning. He got up, showered, dressed himself—complete with buttons, cuffs, and a tie—and made coffee for himself and Ally. “I woke her up with a cup of coffee. That’s huge. That’s when I knew—I’ve got my life back.”

For Ally, the transformation was no less significant. “She was another person being freed from all of the terrible parts of Parkinson’s,” says Bill. “She didn’t have to push me around anymore. She got her time and her peace of mind back.”

The DBS surgery didn’t just restore Bill’s independence. It restored their relationship, freed from the exhaustion of caregiving and fear.

And today, Bill talks about whether Parkinson’s still lurks in the background saying: “To some extent, yes,” Bill says. “But my life is now at the stage where I can make micro movements again. I can do buttons, shoelaces, go fishing… all by myself. I’ve regained so much of what I thought was lost.”

Asked what he’d say to someone newly diagnosed, Bill doesn’t hesitate. “If I knew then what I know now, I wouldn’t have waited so long to decide. Learn everything you can. Talk to people who’ve been through it. Don’t be afraid of treatments like DBS.”

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

Bill Bridger who is living with Parkinsons

He’s unflinching in his endorsement. “I’d go through the whole thing again — surgery, the fear — for just one month of what it’s given back to me.”

Parkinson’s may still be a constant companion, but it no longer dictates the terms of his life. Instead, Bill now walks with intention, sleeps deeply, and pours coffee for the woman who stood by him through it all.

Bill’s story is more than a testament to medical innovation. It’s a reminder of the human cost of chronic illness—and the quiet resilience of those who live with it, and those who care for them.

“I want others to know that carers matter too. Ally carried so much. We both got our lives back, but I’ll never forget the years she gave to keep mine going.”