A century on from its momentous failure, we are still living with the consequences of the collapse of the Boundary Commission. Established to examine where border should be drawn, it ultimately managed to change nothing while also affecting almost everything that followed.

Its decision bolstered Ulster unionism and left swathes of northern nationalists vulnerable, setting the course of the decades which followed.

In his new book, Irish News columnist and historian Cormac Moore sets out the story of the Boundary Commission and its effect on not only high politics but also people on the ground.

In this extract from Root of All Evil – the book’s title is drawn from Northern Ireland Prime Minister and Ulster Unionist leader James Craig’s vivid description of the Commission – Dr Moore sets the scene for an intriguing and infuriating story that continues to resonate today…

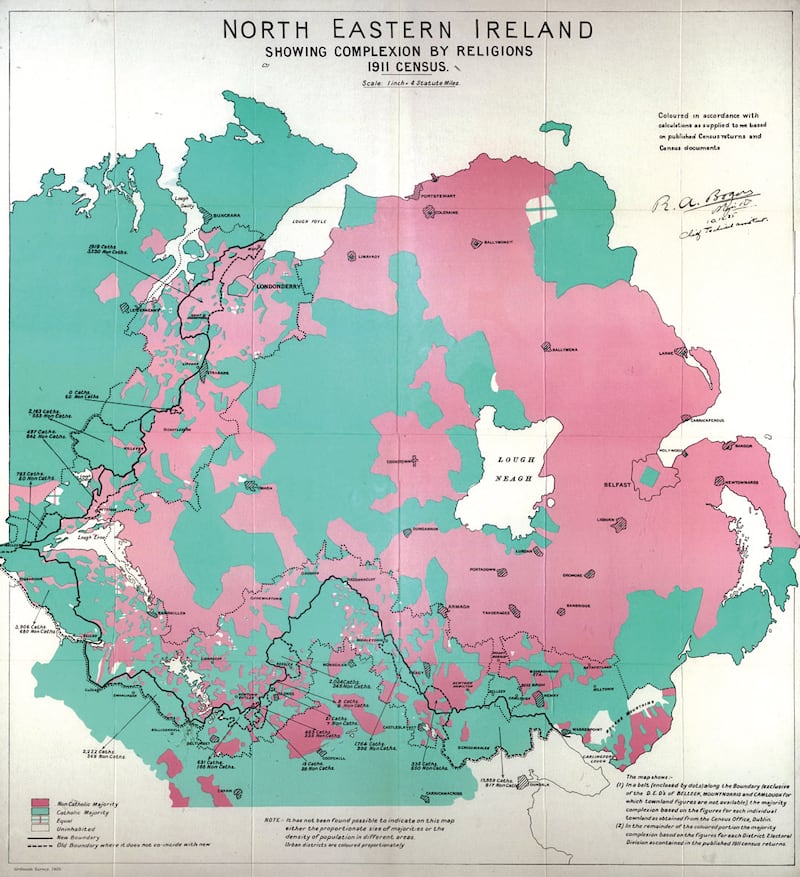

A map produced during deliberations by the Boundary Commission showing religious breakdowns of areas in determining the border

A map produced during deliberations by the Boundary Commission showing religious breakdowns of areas in determining the border

Article 12 of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty states:

“A Commission consisting of three persons, one to be appointed by the Government of the Irish Free State, one to be appointed by the Government of Northern Ireland, and one who shall be Chairman to be appointed by the British Government shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions, the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland, and for the purposes of the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, and of this instrument, the boundary of Northern Ireland shall be such as may be determined by such Commission.”

The Irish Boundary Commission was offered by the British government as a concession to Sinn Féin and Irish nationalism during negotiations on the Anglo-Irish Treaty, in the hope of bringing about a permanent peace between Britain and Ireland.

The Sinn Féin plenipotentiaries accepted the Boundary Commission as a way to limit the consequences of the partition of Ireland, while for the British signatories it offered a path to an agreement on the troublesome Irish question that had dominated British party politics for decades.

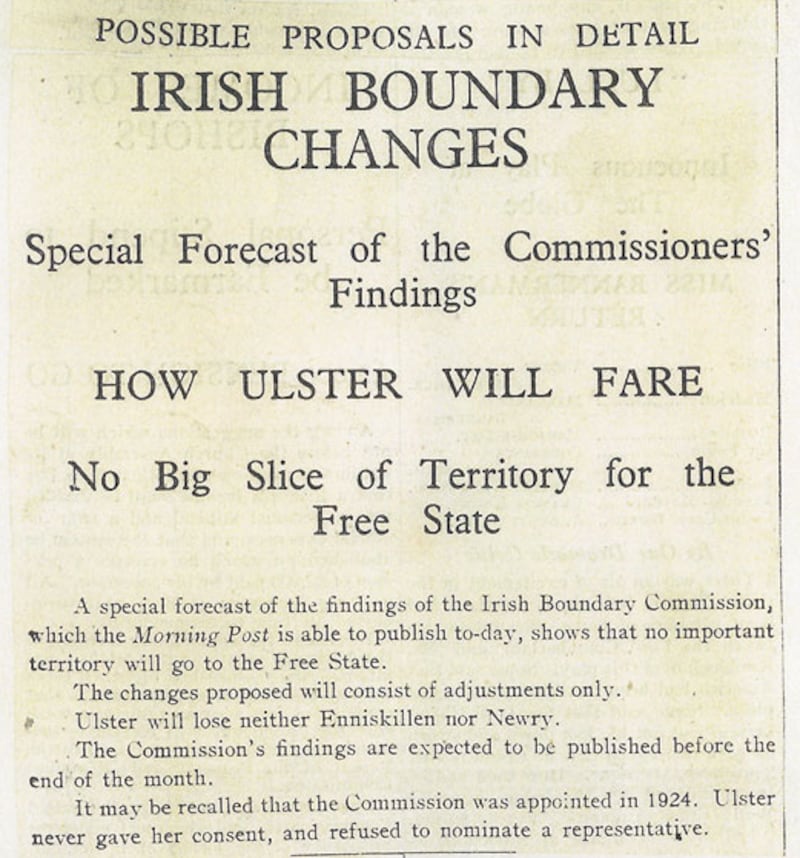

The Morning Post newspaper published details of the Boundary Commission’s recommendations

The Morning Post newspaper published details of the Boundary Commission’s recommendations

Ireland had been arbitrarily partitioned by the British government under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 to appease Ulster unionists, whose opposition to a Home Rule government had been resolute since the Third Home Rule crisis ten years earlier.

Irish nationalists had never accepted this partitioning, but once the already established Northern Ireland government rejected British calls for the inclusion of the six counties in an all-Ireland parliament, the Treaty negotiations pivoted towards the establishment of a boundary commission on Ulster to overcome the impasse and go some way to meet the demands of the nationalists.

Read more: How the Boundary Commission became the ‘root of all evil’ for nationalists

Although boundary commissions had helped to resolve border disputes in post-First World War Europe, the nature and wording of the commission agreed to by Sinn Féin was at the heart of many of the subsequent problems Irish nationalists encountered. The devil was in the details.

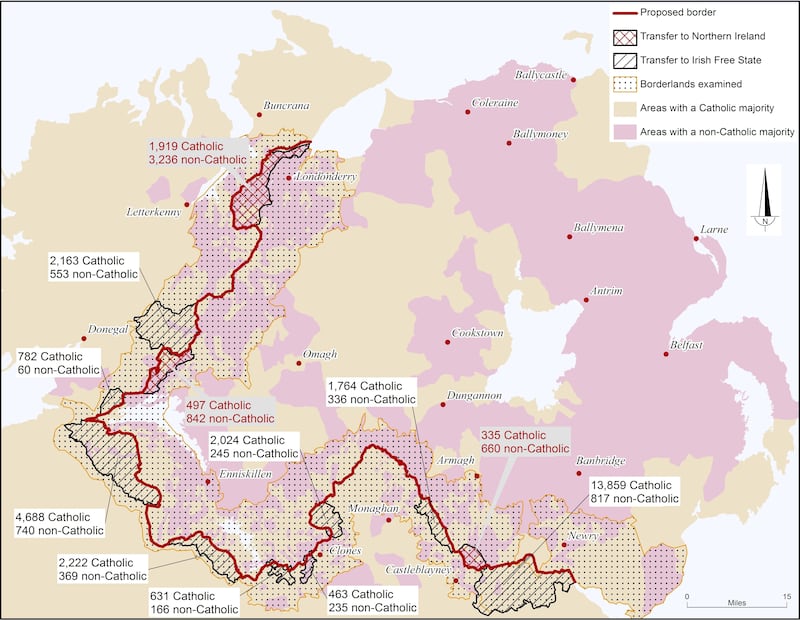

A map showing the Boundary Commission’s proposed changes to the border, including areas marked for transfer to Northern Ireland and to the Free State

A map showing the Boundary Commission’s proposed changes to the border, including areas marked for transfer to Northern Ireland and to the Free State

Under the Treaty, the Irish Boundary Commission was to consist of three commissioners, one appointed by the Irish Free State government, one by the Northern Ireland government, and the chairman by the British government.

The job of the commissioners was to deliberate on the boundary question in Ireland. They were afforded full powers to redraw the boundary line based on those deliberations.

The vague wording of Article 12 gave great latitude to the commissioners to interpret the Boundary Commission’s terms of reference as they saw fit, and with the Free State and Northern government representatives cancelling each other out, considerable control was vested with the British-appointed chairman.

Irish nationalists had never accepted this partitioning, but once the already established Northern Ireland government rejected British calls for the inclusion of the six counties in an all-Ireland parliament, the Treaty negotiations pivoted towards the establishment of a boundary commission on Ulster to overcome the impasse and go some way to meet the demands of the nationalists

The Boundary Commissioners worked intensively for a year, receiving submissions, interviewing witnesses, visiting contested areas and using different tools and data to reach a decision on a new boundary line.

Most of their work, as with the work of the governments beforehand, particularly that of the Free State government and its North Eastern Boundary Bureau, came to nought as there was no change to the border from the one provided for under the Government of Ireland Act 1920.

Despite those efforts and the considerable political controversy that surrounded the Irish Boundary Commission throughout its existence, not one person or acre of land was transferred under the Commission’s remit.

Read more: Fermanagh Nationalists make their case to the Boundary Commission – On This Day in 1925

While the tale of the Irish Boundary Commission could be accused of being one about nothing, given the ultimate outcome, the complex and fascinating story reveals much about the nature of Ireland’s partition and about the Free State’s attempts to assert its independence on the one hand and the British government’s efforts to maintain the reach of its global empire on the other.

James Craig and fellow members of the Northern Ireland cabinet meet at his English home, Cleeve Court, to discuss the appointment of a representative to the Boundary Commission. Picture: E Bacon/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images (E. Bacon/Getty Images)

James Craig and fellow members of the Northern Ireland cabinet meet at his English home, Cleeve Court, to discuss the appointment of a representative to the Boundary Commission. Picture: E Bacon/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images (E. Bacon/Getty Images)

The Irish Boundary Commission, in the words of Kieran Rankin, “served as a crucial catalyst in defining the Irish Free State’s relationship with the British State and in entrenching the territorial framework of Northern Ireland’s six counties that exists to this day”.

The Boundary Commission was a crucial high-stakes matter for the British, Free State and Northern Irish governments from the moment it became a component of the Treaty in late 1921 through to its termination four years later.

Read more: Boundary Problem – Can Free State territory be interfered with? – On This Day in 1925

Nevertheless, this is not only a story of high politics but one of how the decisions from above impacted on people on the ground. Through the different reactions and inputs of people from multiple perspectives, who engaged with the Boundary Commission before and during its convening, the rich source material provides key information on the consequences of the partition of Ireland on day-to-day life, particularly for those who lived close to the border.

The Boundary Commission was chaired by Judge Richard Feetham

The Boundary Commission was chaired by Judge Richard Feetham

The Boundary Commission saga also revealed much about the Irish Free State’s efforts to forge its identity as a newly independent nation of the world while attempting to increase the size of its territory and the amount of people who resided in it, with an ultimate aim of ending partition.

For Ulster unionists, the Commission was seen as an existential threat that required unity within and use of all their experience and allies from Britain to overcome the threat it posed to the territorial integrity of Northern Ireland.

For British stakeholders, most desired that the Commission would disappear altogether or cause the minimum amount of damage to party politics there.

The Root of All Evil: The Irish Boundary Commission, by Cormac Moore is out now

The Root of All Evil: The Irish Boundary Commission, by Cormac Moore is out now

The aim of this book is to explain this incredibly complex, but captivating and important saga in modern Irish and British history. Published in the year of the hundredth anniversary of its collapse, it sheds more light on the intriguing and, particularly for Northern nationalists, infuriating story behind the Irish Boundary Commission, the results of which still resonate deeply today.

The Root of All Evil: The Irish Boundary Commission by Cormac Moore is published by Irish Academic Press and is out now, £19.99