A massive geological transformation is taking place in East Africa, where a hidden force beneath the Earth’s surface is slowly tearing the continent apart.

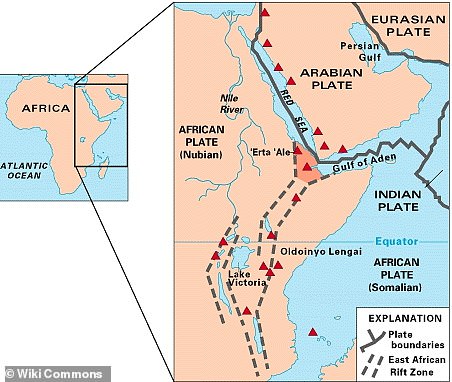

The process stems from the East African Rift System (EARS), which is a 2,000-mile-long rift that began forming at least 22 million years ago and runs through the region where Africa’s Great Lakes are located.

This rift marks the boundary between two tectonic plates: the Somali Plate and the Nubian Plate (part of the African Plate), which are gradually pulling away from each other.

Scientists have now identified a massive upwelling of hot, partially molten rock beneath the region, known as the African Superplume, which is driving this divergence.

Beneath the surface, intense heat and pressure from the superplume are weakening and cracking the Earth’s outer layer, known as the lithosphere.

GPS measurements indicate that the plates are moving apart at a rate of about 0.2 inches per year, roughly the speed at which human fingernails grow.

Over time, this rifting could form a new ocean, potentially splitting off parts of Somalia, eastern Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania to form a new landmass.

While the full separation was previously thought to take tens of millions of years, recent models suggest it could happen in one to five million years.

A massive geological transformation is taking place in East Africa, where a hidden force beneath the Earth’s surface is slowly tearing the continent apart . A 35-mile-long fissure in Ethiopia’s desert emerged in 2005 (pictured)

The African Plate is splitting into two independent tectonic plates – the Nubian and Somali – as a result of a tremendous rising of hot, partially molten rock known as the African Superplume

In the new study, scientists from the University of Glasgow in Scotland used data from Kenya’s Menengai geothermal field to trace the isotopes of the noble gas neon.

This helped the team determine whether the forces splitting Africa apart originate deep within the Earth’s mantle or are due to shallower surface tectonic processes.

They found that the gas likely comes from deep within the Earth, between the outer core and the mantle.

Lead author Professor Fin Stuart said in a statement: ‘We have long been interested in how the deep Earth rises to surface, how much is transported, and just what role it plays on forming the large-scale topography of the Earth’s surface.’

‘Our research suggests that a giant hot blob of rock from the core-mantle boundary is present beneath East Africa, it is driving the plates apart and propping up the Africa continent so it hundreds of meters higher than normal,’ Stuart added.

Using high-precision mass spectrometry, the team also identified a consistent chemical ‘fingerprint’ across a wide area.

This supports the theory that the EARS is fueled by a ‘superplume,’ rather than several smaller sources.

The study provides crucial insights into continental breakup and ocean formation, enabling researchers to comprehend similar processes that have shaped Earth’s surface throughout history.

Earth may be forming a sixth ocean due to Africa splitting in two due to a massive crack growing faster than scientists had predicted. Damage occurred at an intersection in Maai Mahiu-Narok

Countries like Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania could become part of a new landmass, effectively forming a separate continent

EARS spans from Ethiopia to Malawi, and massive cracks have appeared in recent years.

In 2005, a series of over 400 earthquakes in Ethiopia’s Afar region led to the sudden appearance of a 37-mile long crack, providing an example of how dynamic forces works.

Similarly in 2018, a massive crack emerged in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, disrupting transportation and highlighting the ongoing nature of the continental split.

As the rift continues to widen, scientists predict that seawater from the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean will eventually flood the low-lying areas, creating a new ocean basin.

Ken Macdonald, a marine geophysicist, said: ‘The Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea will flood over the Afar region and into the East African Rift Valley, giving rise to a new ocean.’

‘Consequently, this part of East Africa will evolve into its own distinct continent,’ he added.

Countries like Somalia, Kenya, and Tanzania could become part of a new landmass, effectively forming a separate continent.

While landlocked nations such as Uganda and Zambia might gain coastlines, altering trade routes and geopolitical dynamic.

This ongoing rifting leads to frequent earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and large fractures across the landscape.