Artificial Intelligence in genetic medicine offers great potential for improving diagnosis and treatment. However, sustainable AI implementation in clinical settings presents challenges for providers and organizations. This study evaluates the use of Next-Generation Phenotyping tools in the diagnostic process, focusing on F2G. Our review revealed only one study addressing F2G user evaluations [13]. This lack of including healthcare provider viewpoints in AI integration is not unique to genetics, also appearing in other medical fields [28,29,30]. Our research contributes critical factors influencing the adoption and rejection of NGP tools and elucidates the conditions that either facilitate or hinder their utilization within clinical workflows in genetics.

Our review highlighted that F2G has successfully mastered the translation from usage in a research context into routine care, a critical step for AI tools in healthcare [29]. Although numerous studies utilizing F2G to report case descriptions, they frequently fail to include specific workflow details. The predominant focus on performance metrics, such as the accuracies of DeepGestalt or GestaltMatcher, often neglects clinicians’ experiences, which is essential for the successful adoption of novel technologies [31, 32]. Marwaha et al. employed a brief questionnaire to capture user opinions one-year post-implementation at a single institution, providing an initial overview of user experiences [13]. Building on this, our study employed a semi-structured interview methodology with participants from diverse hospitals to enhance these findings. Although Marwaha et al. found F2G to be beneficial for diagnostic decision-making, they also identified significant reservations concerning accuracy, informed consent, confidentiality, and patient uptake [13]. In alignment with these findings, our participants reported favorable usability of F2G; however, they expressed concerns regarding the informed consent process.

Our interviewees highlighted that the use of F2G is just one component of the diagnostic process. Moreover, all users reported using it in addition to molecular genetic analyses. The extracted workflows align with research on integrating AI into work processes [28]. Interviewees described F2G as easy to use and evaluating its usefulness positively, which are key contributors for the intention to use of a novel technology [33]. Additionally, we identified several key factors impacting the decision to actually use F2G. Time pressure was the most frequently cited factor influencing participants’ use of F2G, aligning with findings from other AI integration studies [18, 22]. However, time pressure was noted as less intense in genetics than in other specialties like pediatrics. Most users reported utilizing F2G for dysmorphic patients, while some did so out of curiosity or when a suspected condition was unclear. This is noteworthy, as the performance of these tools relies on the distinctiveness of facial dysmorphisms [7]. To optimize the cost-benefit ratio of time and AI performance, participants reported to select suitable patients for facial analysis, as indicated by their usage patterns. For most users, specific patient characteristics were central to their decision to use F2G, as reflected in their responses about how frequently they utilize the tool. Given the high proportion of diseases with facial dysmorphism [2, 3], NGP tools will continue to have ample use cases. In a scientific context, however, the analysis of less distinct disorders could also be useful, as AI can also recognize patterns that are not always apparent to humans [34].

An analysis of the workflow revealed that the consultation and patient photography are standard steps of genetic assessments. This may account for the observed absence of specific facilitators or barriers linked to F2G in this stage. However, from obtaining patient consent onward, additional implementation factors for successful F2G integration were identified. We observed more facilitators than barriers, potentially indicating a good workflow fit. The distribution of facilitators and barriers across different elements of the work system model highlights the complexity of adopting AI tools like F2G. Facilitators such as usability, time investment, and accessibility are closely tied to the AI solution itself namely the element of tools and technology, emphasizing the importance of good design when implementing AI in clinical settings. In contrast, barriers like obtaining consent and additional work steps are linked to the element of tasks, suggesting that administrative processes may hinder smooth integration. Additionally, the lack of work-issued smartphones or tablets for many participants presents a significant obstacle, forcing a reliance on external photographers and desktop computers, which complicates the workflow. These issues point to broader organizational challenges, such as the need for better local support and more seamless IT integration, which were met with varying levels of satisfaction among participants. The amount of barriers and facilitators associated with the element organization highlights the impact organizational support could have, especially as it was also among the factors the inform users’ decision to use F2G. For example, the process of obtaining consent was a central barrier to use, which could be mitigated by the organization providing standardized forms for using F2G. It is crucial to clarify that patient consent is only required for research-related activities, such as the technical validation of the AI algorithm’s performance. Similar to numerous Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms, NGP software is frequently designated ‘for research purposes only’, which may lead to user confusion. If these tools are approved as medical devices for decision support in the future and become part of accredited workflows, this usage would typically not necessitate additional patient consent. The work system element ‘people’ was identified mostly for task-related facilitators and barriers, but three users also identified their supervisor as having a strong impact on their workflow using F2G. We identified no facilitators or barriers related to the environment, likely because the introduction of F2G as a web-based AI solution did not lead to any changes.

Salwei and Carayon outlined three essential sociotechnical considerations for integrating AI into healthcare systems: the alignment with work systems, compatibility with existing workflows, and enhancement of clinical decision-making processes [17]. Through analyzing the work system barriers and facilitators, our study was able to demonstrate an overall good fit of F2G in the work system, supporting their first consideration. In examining how F2G fits into the workflow and the positive feedback regarding the time required to use it, we found that it integrates well with the existing workflow, which supports the second consideration. Although F2G is not a mandatory step in the diagnostic process, participants found it valuable for diagnostic purposes and case discussions, which aligns with findings from Marwaha et al. [13]. This supports the third consideration regarding workflow integration. Overall, we found that F2G is a well-integrated AI solution, yielding positive outcomes such as enhanced user satisfaction, shorter time to diagnosis, and greater acceptance of the technology. Clinicians’ positive appraisal regarding the use of F2G corresponds with the primary advantages participants sought from AI in genetics, namely improved diagnostics and increased efficiency, which are relevant across healthcare setting [35, 36]. The information gained from this study can be used to successfully implement other NGP tools such as GestaltMatcher and Phenoscore [4, 7]. Even though the scientific benefit of these tools has been already proven by demonstrating their accuracy, their seamless transfer into clinical routine is essential to actually promote significant improvements in diagnoses of rare genetic disorders. This can only be achieved by identifying and addressing concerns of clinicians during the implementation ensuring a smooth fit into the workflow.

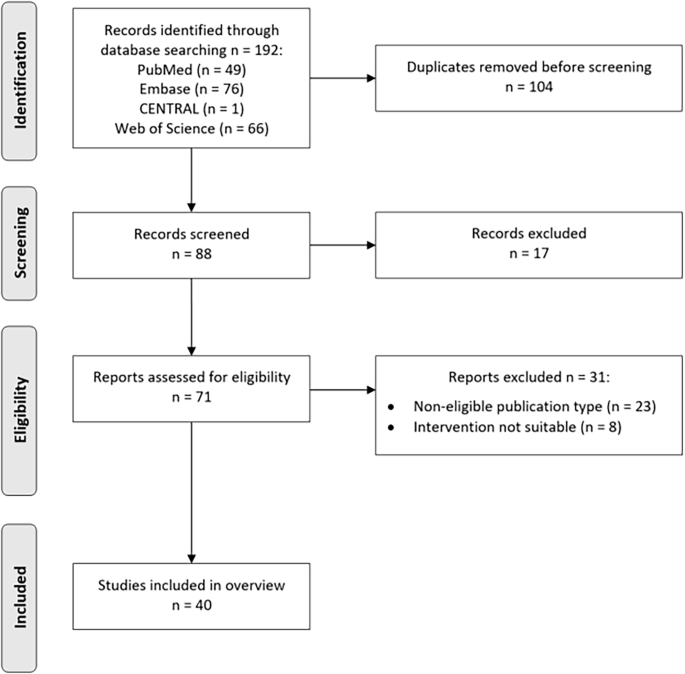

Participants generally viewed AI and NGP tools as beneficial for improving care processes, efficiency, diagnostics, and reducing healthcare workloads. However, they expressed concerns about potential misuse, over-reliance, bias, and loss of professional skills. This resonates with a study by Hallowell et al. which explored stakeholder perspectives on NGP technology [37]. They additionally highlighted that NGP tools could democratize access to diagnoses—an aspect not raised in our interviews, likely due to the widespread availability of genotyping methods in Germany. This shows a limitation of our study: all participants were recruited within Germany to ensure comparable workflows. Given that F2G is deployed globally, future studies should examine workflow integration across different countries and healthcare settings to identify universally applicable recommendations. Additionally, our literature review featured a rapid synthesis of available studies involving F2G, whereas a more systematic and rigorous approach might have been more effective in ensuring that all relevant studies were included (i.e., from gray literature). Although our response rate was lower than expected, sufficient data saturation was achieved, as later interviews did not reveal new themes. It must be noted, that we aimed to include both pediatricians and geneticists; however, only geneticists responded. Pediatricians, who may benefit most from NGP for patients with facial dysmorphism, often have shorter visit times, making their perspective on the cost-benefit ratio of NGP particularly valuable [38, 39]. Future studies should prioritize this user group to assess their specific needs and challenges. Finally, the limited number of interviews, particularly with non-users, may have introduced bias. Future research should explore detailed comparisons between various user groups, possibly examining correlations with diverse user characteristics [40].

Our study enhances the existing literature on NGP technologies by evaluating the integration of F2G as a specific use case across various institutions. Through clinician interviews, we mapped the workflow of using F2G, which has been effectively incorporated into routine practice, despite being an additional step in the diagnostic process without replacing molecular genetic testing. This indicates that NGP technology can significantly improve healthcare efficiency and quality, provided that clinicians’ acceptance is further enhanced. Our analysis of facilitators and barriers using the work system model underscores essential considerations for future design and implementation, particularly the importance of user-friendly design and ensuring organizational support.