It’s a little fussy to set up, but gives real insights into how your body is responding to hot weather exercise.

We may earn a commission from links on this page. Deal pricing and availability subject to change after time of publication.

I hate running in the heat. Not only does it feel awful, but I get slower and slower as the temperature rises. Instead of running 10-minute miles, I’ll be slogging along at 11 or 12 minutes each. It’s not just me, of course: we’re all slower in the heat, and slower still when it’s both hot and humid.

But our bodies can adapt to the heat. That first hot summer day is a doozy, but by August I’m usually surviving pretty well, if not thriving. Athletes who need to perform well in the heat will often follow heat training protocols to be sure they’re ready in advance for hot-weather races.

And this is where a gadget called the Core 2 Thermal Sensor comes in. It’s a little smart slab of plastic that you attach to your heart rate chest strap, and it measures your body temperature while you train. From that data, you can learn how well you’re adapting to the heat, and you can use it to guide you through a heat-training protocol so you can adapt faster and more efficiently. You can also use it when you’re running a race to make sure you don’t overheat—train hot, race cool, as the saying goes.

The Core company sent me a sensor to train with, and I’ve been using it for a few weeks. Spring weather is beginning to turn to summer, so I’m feeling the effects of hotter weather, but I also need to seek heat out if I want to encourage my body to adapt to the hotter conditions that are coming.

I’ll give my initial thoughts on this device based on these past few weeks of use, and then I’m going to continue working with the sensor over the summer. Whenever I write about heat adaptation or hot weather running, I’ll pull in data from my experience with the Core 2 sensor—and then I’ll return at the end of the season for some final thoughts on whether I thought training with the sensor was worthwhile. This gadget, cool as it is, costs $294.95 (plus, at the moment, an extra $31 for shipping and tariffs), so it needs to be pretty darn useful to be worth that cost.

The metrics and what they mean

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

The Core 2 sensor gives you three numbers whenever you wear it:

-

Your skin temperature

-

Your (estimated) core temperature

-

A “heat strain index,” or HSI, broken into one of four zones.

Your core temperature is the temperature inside your body, specifically inside your torso (your core). Some studies test this with a rectal thermometer, or with a probe that can be swallowed. When you take your kid’s temperature at their mouth, ear, or armpit, you’re trying to get a measurement that is close to this number. A normal core temperature for a healthy human at rest is 98.6 degrees, give or take a degree or two.

Skin temperature is, of course, the temperature on the outside of your body, wherever it’s being measured. The Oura ring and the Apple Watch, to name a few, have temperature sensors that let them monitor skin temperature.

I was perplexed at first: how can one device know the temperature in two different parts of your body? I asked Brian Maiorano, the coach liaison at Core. He explained that the device contains two sensors. Skin temp comes from a regular temperature sensor, similar to what’s in other wearables. And then there is a heat flux sensor, which for the moment I am content to not entirely understand. (It measures the flow of heat energy rather than temperature, which is different somehow.)

Core has an algorithm that can estimate core temperature from heat flux sensor data, but it’s only valid during exercise if the device knows the athlete’s heart rate at that moment. That’s why you need to pair the Core 2 sensor to a heart rate chest strap. Importantly, the sensor is for use during exercise, but not during passive heat sitting in a sauna—you have to log sauna sessions manually.

From the skin temperature and core temperature, Core can generate a heat strain index, or HSI. This gets categorized into one of four heat zones, so if you’re used to heart rate zones or cycling power zones, you’ll be right at home. With a glance at your watch during a workout, you can tell whether you’re in:

-

Heat zone 1: No heat strain. Either your core temp isn’t elevated, or it is but your skin temperature is low enough that you must be cooling yourself off quite well. This is the ideal zone for running a race, or for taking a break from heat training.

-

Heat zone 2: Moderate heat strain. You’re warm, and maybe your performance is slightly affected.

-

Heat zone 3: High heat strain. Your skin and core temperatures are both high, you’re probably sweaty and exhausted, and you’re definitely not running as fast or performing as well as you would in a lower zone. This is the zone that helps you the most in heat training, though!

-

Heat zone 4: Extremely high heat strain. This is the danger zone, and you’ll want to get out of it as quickly as possible—stop exercising, cool down, etc. You should also be on the lookout for signs of heat illness, like dizziness, cramping, and nausea.

Safety is important when you’re exercising in the heat, and I wouldn’t trust a device (no matter how good its algorithm claims to be) to tell you when you’re safe to keep going.

Everything I’ll discuss about heat training should be taken in the context of stopping if you don’t feel good, and ideally being around others who could help you if something goes wrong. At a core temperature of about 104 degrees, your body can no longer cool itself effectively, leading to potentially deadly consequences for your brain and heart. This is known as heat stroke. At that stage, you may not be coherent enough to call 911 for yourself; somebody may have to do it for you.

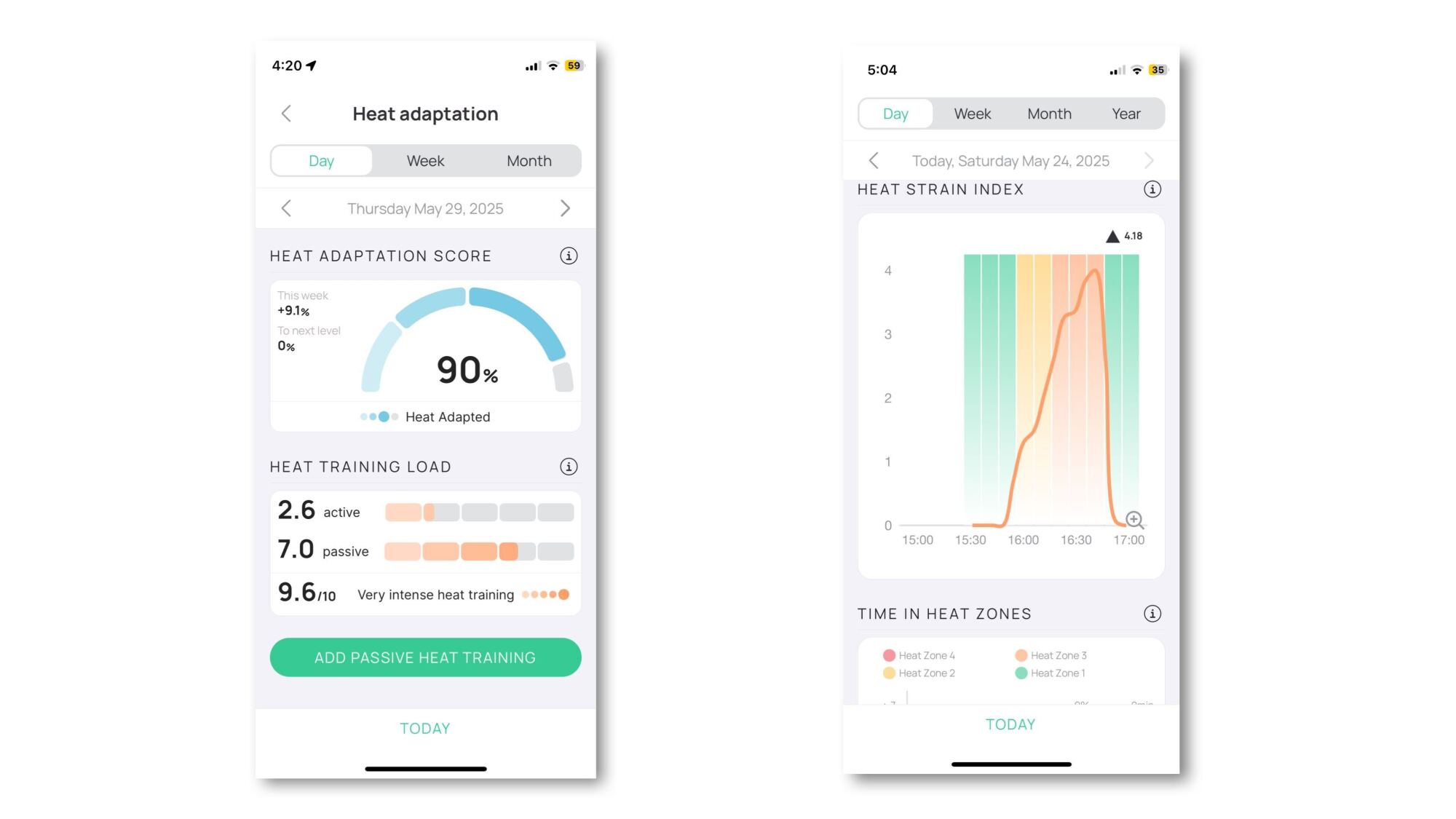

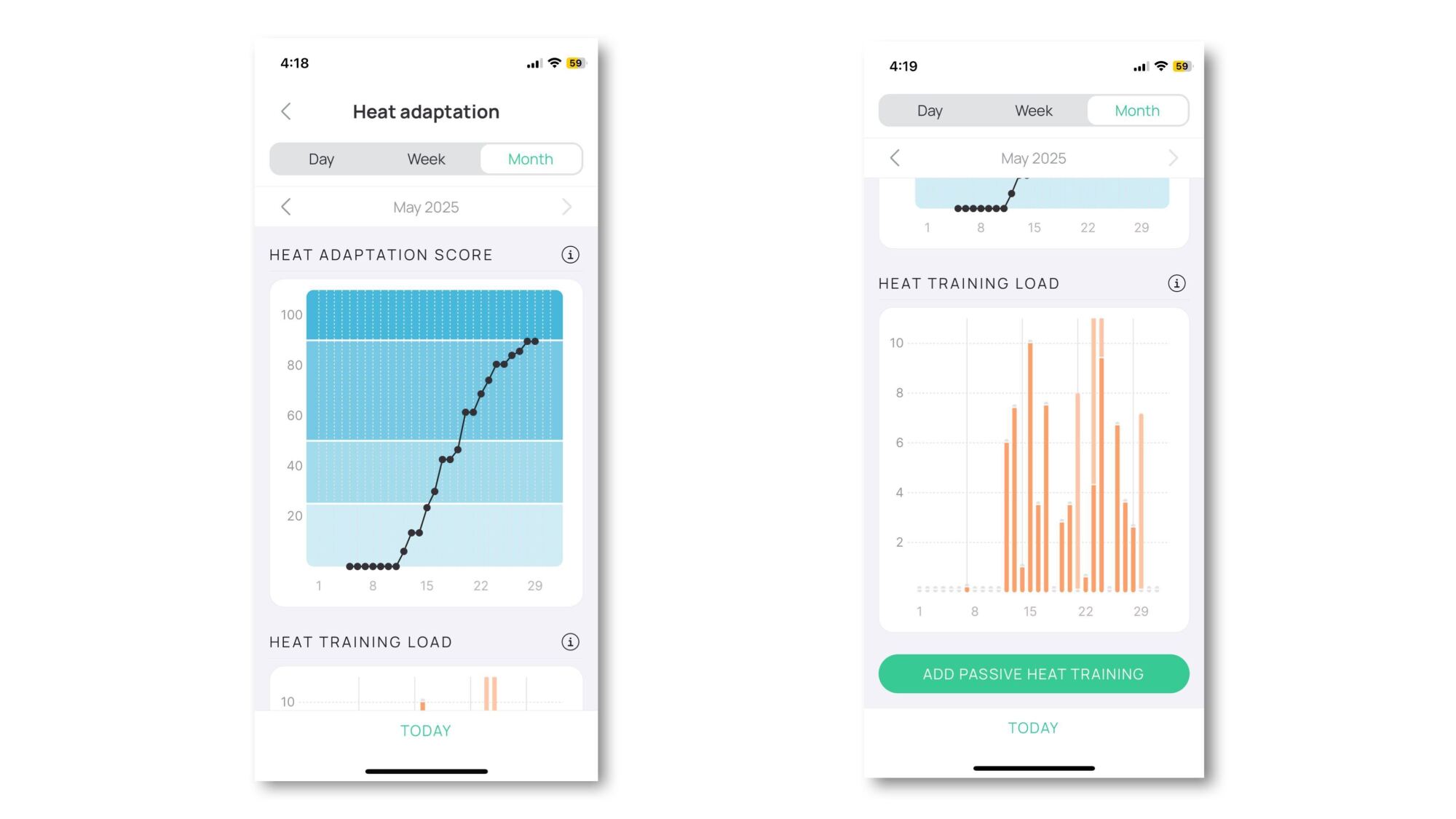

Once you dive into the Core app, you’ll see a few more numbers, including a Heat Adaptation Score and a Heat Training Load. The app also totals up the amount of time you’ve spent in each heat zone. I’ll show you more about those metrics in the heat training section below.

Setup

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

To use the Core 2 temperature sensor, you’ll need a heart rate chest strap and a compatible watch, like a Garmin. I’ve got both—my trusty Coospo (25 bucks and it’s lasted me years) and a selection of watches. I mostly used it with my Garmin Forerunner 265s and the Forerunner 570 that I’m testing for a review.

Currently, pairing is available for watches and bike computers from Garmin, Coros, Wahoo, Suunto, and Hammerhead. The Apple Watch has been supported in the past, but a note on the Core website says there’s an issue with it at the moment and it’s been removed—hopefully temporarily.

Setup has a lot of steps, but it’s not difficult. There’s a full setup guide on Core’s website here, but the basics go like this:

-

Install the Core app on your phone

-

Use the Core app to pair the sensor to your heart rate monitor

-

Install the Core app to your watch (for example, Garmin’s Connect IQ store has a Core data field you can download)

-

Pair the Core sensor to the watch within the Connect IQ app

On a Garmin, you also need to add the Core data field to the activities you plan to use it with. For me, that meant the Run, Treadmill Run, Track Run, and Trail Run activities. Here’s what I did:

-

Go to the Run activity, then go into the menu and select Run Settings and Data Screens.

-

Scroll past your normal screens and select Add New to add a new screen.

-

Choose a screen with just one data field, and assign it to Connect IQ Fields > Core.

You can also add the Core data field to any of your normal screens, alongside pace and distance or whatever you like to track. As Maiorano told me, you don’t need to look at the Core data field during your run, you just need to have it in your setup. So if you don’t want to change your usual data screens, you can just stick the Core field at the end of your carousel of screens and ignore it.

(Interestingly, the single-field Garmin screen will display multiple different metrics: your skin temp, core temp, your HSI, and the zone you’re in. If you use this field on a screen with other fields, some of those things will be omitted to save space.)

I hit a wrinkle when, mid-testing, I got a Forerunner 570 to review. The Connect IQ data field for the Core sensor wasn’t available for the new watch. I grumbled to myself for a few days, wondered whether the team knew there was a new watch out, and then realized I should probably just contact customer support to ask. They responded five days later to let me know they updated the app, and sure enough there it was for me to download. Score one for responsive customer service.

What it’s like on a run

Left: before a workout, nice and cool. Right: after a workout, with a high body temperature. (These were not the same workout.)

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

Importantly, you need to turn the sensor on before you expect it to start collecting data. Shake it until the little light turns green. (I forgot to do this on my first run.) The battery lasts for at least a week of daily workouts; I didn’t track an exact number of hours, but I’ve been using it for 18 days and only charged it once, about 12 days in. When the battery starts to run down, you’ll get a low battery icon on your watch screen and in the app.

When you go for a run, the Core sensor reads your heart rate data from the heart rate strap, which it uses to calculate your core temperature. The Core sensor then sends all your temperature data (skin temp, core temp, HSI) to your watch.

The watch can display that to you while you’re running, but even more importantly, it saves your temperature data to the activity file that it creates—alongside your normal data like distance, pace, heart rate, and so on. After your workout, that data syncs back to the Core app, which can tell you how your heat training is going.

So let’s go for a run. First, you need to remember your dang chest strap. I normally wouldn’t use a chest strap on every run, but I suppose that’s changed now that I’m keeping track of my heat training. I bring it every time, because there’s no way to get credit for the heat I endured if the Core 2 sensor wasn’t with me reading my data.

What do you think so far?

Next, you have to make sure the Core 2 sensor is on the chest strap. There’s a little plastic sleeve for the sensor that slips onto your chest strap. (It should fit most straps; mine slipped on without a problem.) As the packaging notes, the logos on both the sleeve and the sensor should face away from your body.

Sorry about the purple stain, I guess it didn’t get along with my purple sports bra.

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

The sensor snaps into the little sleeve, and you should wear it close to your armpit. Mine ended up about midway between my armpit and the heart rate sensor at center chest—so, roughly under my right boob. It was mildly annoying for the first half of my first workout (and I tried a bunch of different positions, none of which were any more comfortable) but I got used to it pretty quickly. These days, I strap it on and don’t even notice.

During the run, if I’m starting to slow down and I wonder if it’s because of the heat, I’ll scroll to the Core screen and see what heat zone I’m in. If it’s zone 3, I think “oh hey, I’m getting some heat training benefit from this!” which is a lot better than my usual thought process of “ugh, this sucks and I’m so slow.”

And finally—one of my biggest gripes—you need to make sure your data screens are set up properly. One day I brought the sensor to the gym, only to realize after my warmup that I hadn’t been wearing the sensor. Right! OK! I put it on. Then after my first interval, I realized that I hadn’t set up the Treadmill Run profile to include the Core data field. I was able to add it mid-run and the data was available from that point forward, so all was not lost. But that’s a lot of extra stuff for a forgetful person who is already trying to keep track of other things during a hard workout.

Tracking your heat training

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

After a run, I can see my temperature data in the Garmin app. There, it’s just another chart next to my pace, heart rate, and everything else. But what’s more interesting is to go into the Core app, which tells me about the big picture of how my heat training has been going.

The home screen shows my heat adaptation score as a percentage (I’m up to 90%, which it describes as “heat adapted”) and my heat training load for the day (zero as I write this, but I got a score of 9.6 out of 10 yesterday from a hard workout plus a sauna session).

You can get a maximum of 10 as your heat training load; if you hit 10, you’ll get a warning in the app, and the score won’t go any higher (presumably they don’t want people chasing high numbers to brag about). For comparison, earlier this week I did an easy run on a drizzly, 53-degree day. I got a 3.6 out of 10, just because my body warmed up a bit during the run. This level of heat exposure contributes to my adaptation, in the sense that it’s better than lazing around in the air conditioning all day.

When it comes to my heat adaptation score, I started out as a “thermal rookie,” less than 24% adapted, but over the past few weeks I climbed up through “heat accustomed” to “heat adapted,” and am on the cusp of being a “heat champion” at 90% heat adapted. To get this far, I’ve been seeking out hotter weather rather than hiding from it, and sometimes adding on a sauna session after a run.

On (not) using the Core 2 sensor in the sauna

Credit: Beth Skwarecki

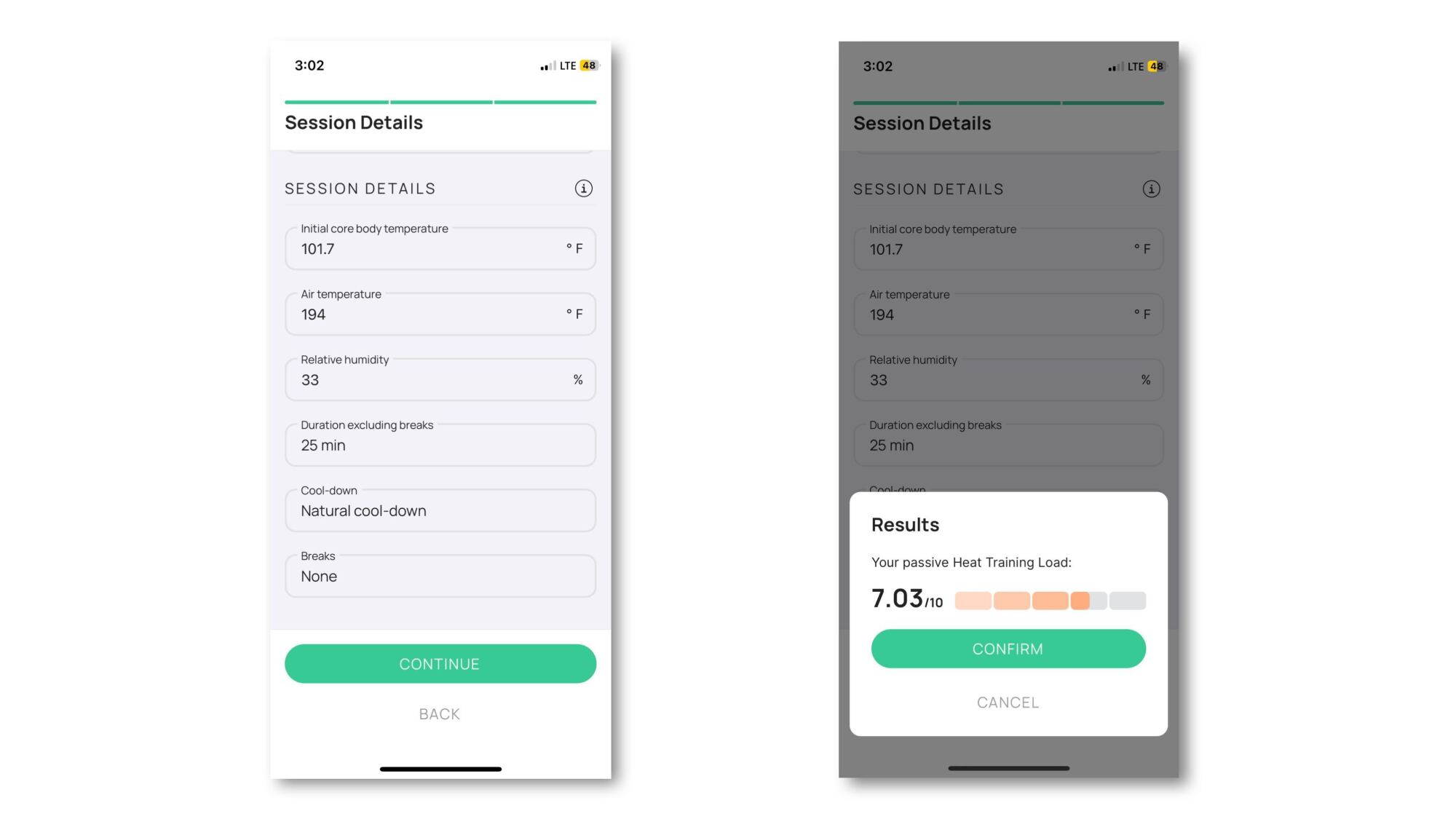

Sauna sessions fall under “passive heat training,” and you have to log those manually. Sauna heat isn’t good for the device, but just as importantly, it won’t be accurate in the sauna. So you tap “add passive heat training” in the app, and tell it about your sauna session.

When I log a session, I need to know my core temperature at the start of the session, and the temperature and humidity of the sauna. I’ll also fill in whether I took any breaks, and whether I cooled myself down with a cold shower or not.

My first thought was “how am I supposed to know all that?” but the most critical thing—my core temperature—can come from the Core 2 sensor before I enter the sauna. Passive heat sessions make the most sense when you do them after a workout, after all, since your core temperature is already high. (If you start a sauna session cold, your first 15 minutes or so are just getting your body temperature up. Step in the sauna right after you step off the treadmill, and you can bypass those 15 minutes.)

So I check my core temperature right before taking off the sensor, screenshot that, and then go straight to the sauna. The temperature is displayed on a control panel right outside the door. The humidity isn’t labeled, but for some reason I am the kind of person who owns a pocket-sized humidity gauge, so I just bring it with me. (The humidity in my local sauna has been around 30% lately, if this gadget is correct. The default in the app is 10%.)

If I skip my heat training for a few days in a row, my heat adaptation score starts to level off or even drop. I try to get a heat training load of at least 5 for at least two or three days in a row before taking a break. This approach seems to be working well for me; I’m definitely more comfortable with hot weather exercise, and the other day I noticed with pride that I was way sweatier than anyone else in the sauna. (Heat training makes you sweat more, the better to cool yourself off. Gross, but useful.)