This is the fifth in a series on The Athletic looking back at the winners of each men’s World Cup. The previous four articles have looked at Uruguay in 1930, Italy in 1934 and Italy again in 1938, before Uruguay themselves won it for a second time in 1950. So it’s about time someone else stepped up…

Introduction

There are two clear examples in World Cup history of the most exciting team at the tournament, and the neutral’s favourites, being foiled by West Germany in the final. The most obvious example is the Netherlands in 1974, but two decades beforehand, Hungary experienced almost exactly the same thing.

If anything, it was even more egregious because this legendary Hungary side had previously destroyed West Germany 8-3 in the group stage — a huge victory, even by the standards of a World Cup that featured a record goals-per-game tally of 5.38. At that point, there seemed little chance anyone would stop the Olympic champions Hungary, let alone the Germans.

Hidegkuti (2nd R) scores the fifth past Heiner Kwiatkowski (22) in the group-stage game (STAFF/AFP via Getty Images)

But this was a remarkable triumph for West Germany, less than 10 years after the end of the Second World War. It was the first tournament they’d entered since then, having been banned from FIFA leading up to World Cup 1950. While overt demonstrations of nationalism had been avoided going into the tournament, the shock success (half the teams were seeded going into the tournament, and West Germany weren’t among them) brought a newfound sense of national pride as West Germany rebuilt itself after the war.

The manager

A talented striker who played three times for his country, Sepp Herberger is perhaps more notable for having served in both World Wars, although according to his own testimony he was never involved in armed conflict.

In keeping with other German managers in the 20th century, he served as assistant before becoming the outright manager, leading Germany at World Cup 1938, and then having a 14-year second spell in charge from 1950 onwards.

Herberger was both a good tactician and a canny man-manager. He used to motivate his players by reading out critical press reports from back home, telling them to prove journalists wrong. He thought as much about which players should room together as he did his side’s formation. He was variously depicted as both a strict disciplinarian and also an emotionally intelligent father figure to the players.

When he returned home after the tournament, he found that his home had a new address — he now lived on ‘Sepp-Herberger-Strasse’.

Tactics

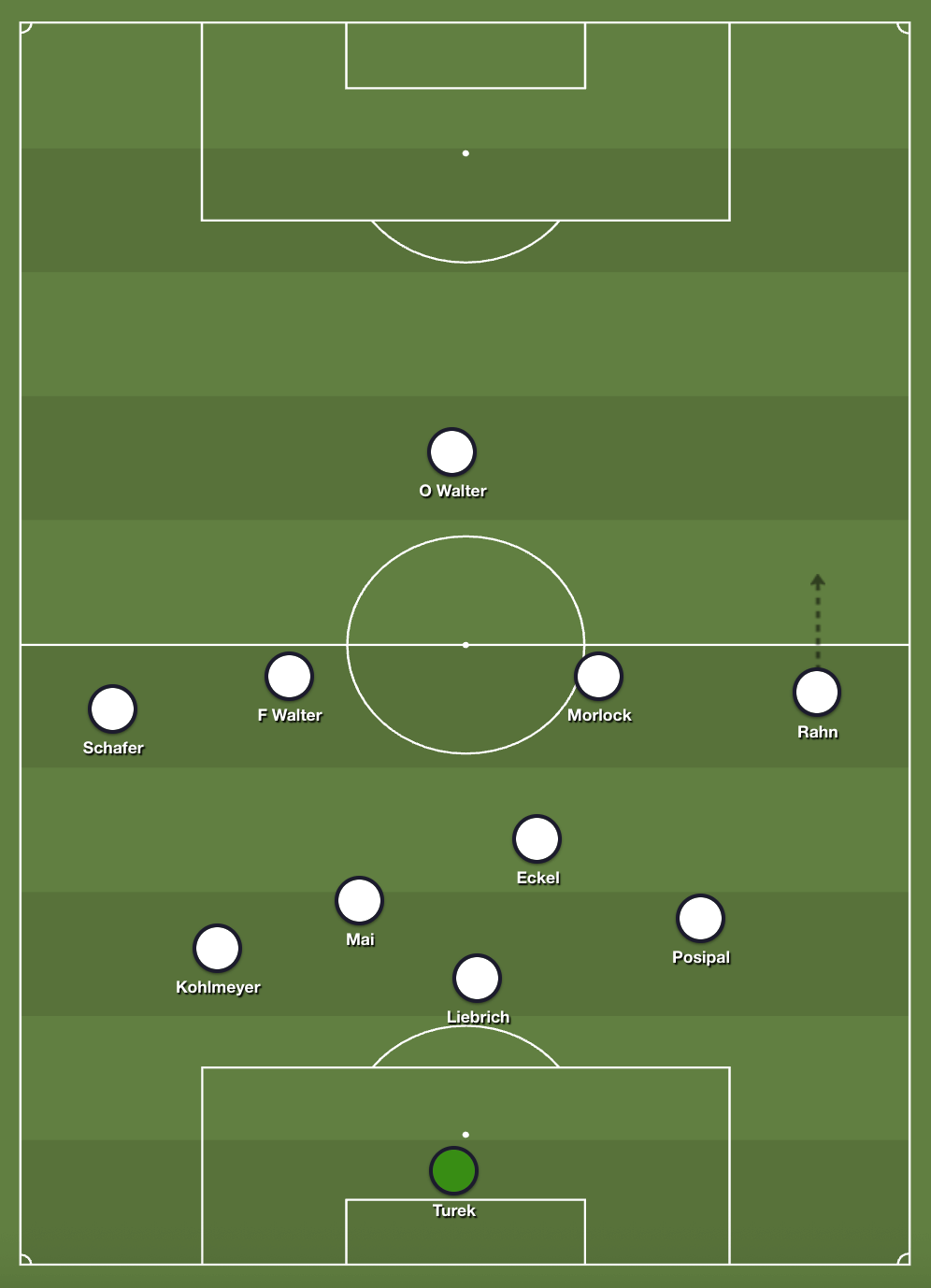

The WM formation was on the way out. Hungary were the poster boys for the shift away from that system. But Herberger was canny too, and his approach for that final was first and foremost based around stopping Hungary.

West Germany’s formation in the final started to resemble something like the systems we would recognise in the modern era, with left-half Karl Mai performing a man-marking job on Sandor Kocsis and ending up as more defender than midfielder. Kocsis had scored 11 goals in the tournament, but was relatively quiet in the final.

The job of tracking Nandor Hidegkuti — whose drifts into deep positions had flummoxed England in Hungary’s famous 6-3 win at Wembley the previous year — was handed to midfielder Horst Eckel rather than a defender.

In turn, captain Fritz Walter and Max Morlock played deep and were regularly involved in build-up play. There was an impressive level of fluidity in the side, with right-winger Helmut Rahn tending to stick to his role, but the others rotating within matches. Rahn was an explosive and unpredictable winger, somewhat out of keeping with what Herberger wanted from his players. His quality, though, was impossible to ignore and he scored twice in the final, when Herberger encouraged his players to attack down the flanks rather than through the middle.

But the most-discussed element of Herberger’s tactics was his team selection for the 8-3 group stage defeat to Hungary, where he made seven changes from the opening day win over Turkey. Clearly, this was not a tactical decision in the traditional sense, and there was such anger from the hordes of travelling German supporters that some called for him to resign midway through the tournament (not an entirely unlikely concept — in this World Cup, Scotland manager Andy Beattie resigned after his side’s first game).

What was the reason for his selection? It seems clear Herberger was resting his best players as he didn’t think his side had much chance of beating Hungary. Some suspected he was also trying to engineer his side coming second in the group, to be on the easier side of the knockout stage bracket. And, once West Germany had prevailed in the final, the story became that Herberger had fielded a weakened side to lure Hungary into a false sense of security. Maybe that was the outcome, but was it really the intention?

Star player

While centre-halves had been the dominant figures in international football before the Second World War, their retreat into central defence meant the inside-forwards became the stars in the middle part of the 20th century.

This West German side was no different. Fritz Walter, whose brother Ottmar played as the side’s centre-forward, was a prodigiously talented inside-left who was adored by Herberger, who gave him special treatment and handed him the captain’s armband. This was despite Walter coming in for particular criticism in the years before this success, especially after a 3-1 loss to France in 1952. He offered to retire from the national side, but Herberger insisted he remained the side’s main man.

Fritz Walter with the World Cup (Keystone/Getty Images)

That paid off in 1954. Although criticised for his sluggishness in the group stage, he came alive in the 2-0 counter-attacking quarter-final victory over Czechoslovakia, and scored two penalties in the 6-1 semi-final win against Austria. But it was about more than just goals — he was the side’s creative force, roughly their equivalent of Puskas.

Walter had contracted malaria during his time as a prisoner of war, and found it difficult to play well in hot conditions. Most of World Cup 1954 was not to his liking, but in the final week the temperatures cooled, and the final was played on a damp day.

Walter was the first person to be awarded honorary citizenship of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate — the award has never been handed out again.

You might be surprised to learn…

West Germany tended to come on strong in the second halves of matches. Immediately after the tournament, plenty of credit was given to cobbler-turned-entrepreneur Adi Dassler — the founder of Adidas — for designing innovative new boots featuring screw-in studs, allowing the players to choose short or long ones according to the weather, supposedly a major advantage when the conditions changed midway through the final.

But there may have been a less glamorous explanation. After the final there were reports of used syringes being found in the West Germany dressing room. The team officials insisted the players had been injected only with vitamin C, an explanation later ridiculed by medical experts, who said it would have been no more effective than eating an orange. Several players contracted jaundice in the aftermath, experienced further health problems, and many later admitted receiving injections at the tournament.

Investigations into this continued for over half a century. A 2013 report from Humboldt University suggested the syringes contained methamphetamine, as detailed further by The New York Times.

The final

A genuinely thrilling game that featured two goals for either side in the first 20 minutes. Both continued to play good football, until the game was won in the closing minutes.

The real story was that Puskas was back in the Hungary side for the first time since getting injured against West Germany in the group phase, and despite not being fully fit, he opened the scoring with a calm finish after a loose ball in the box fell his way. Hungary quickly made it two after a terrible mix-up between left-back Werner Kohlmeyer and goalkeeper Toni Turek. But 2-0, of course, is a dangerous lead.

Morlock scores in the final (Keystone/Getty Images)

Max Morlock got one back with — it must be said — the third scrappy goal of the game, turning home a deflected cross. Then Rahn arrived at the far post to fire home a deep corner, after Hungarian goalkeeper Gyula Grosics tried to claim, but was blocked off by Hans Schafer. Grosics always claimed he was fouled, but by the standards of 1950s refereeing it’s not a surprise the goal was given.

Hungary had the better chances. Hidegkuti hit the post, Kocsis headed against the bar, Turek made some fine saves, and Kohlmeyer made up for his earlier error with a couple of goal-line clearances. Comprehensive statistics aren’t available, but it’s fair to suspect that Hungary won on the xG.

The defining moment

In West Germany, the defining moment was Rahm’s winner in the 84th minute, when he surprised the Hungary defence by cutting inside onto his left foot and firing into the far corner — a goal that feels very modern in this age of inverted wingers.

In Hungary, the defining moment came in the 86th minute, when Puskas squeezed home what he thought was an equaliser, only to be denied by an offside flag from Welsh linesman Sandy Griffiths. There are no clear television pictures to show whether the decision was correct.

But maybe the defining moment came in the group stage meeting between the sides, when Puskas was kicked in the ankle by German centre-back Werner Liebrich — the third time he’d attempt to foul Puskas — which meant he missed the subsequent games up until the final, when he played despite clearly being short of 100 per cent fitness.

Were they definitely the best team?

No. The final was Hungary’s only defeat in a long run of 49 matches. They’d thrashed the (second string) West Germany side 8-3 in the group stage. They’d defeated the two ‘finalists’ from World Cup 1950, Brazil and Uruguay, 4-2 in quarter-final and semi-final respectively. They’d coped for most of the tournament without Puskas, the world’s best player. Throw in the doping allegations, and Hungary’s loss must be considered one of football’s greatest injustices.

Hungary never made it past the quarter-finals again, and on their most recent three appearances — 1978, 1982 and 1986 — didn’t make it past the group stage.

The boost to West Germany shouldn’t be underestimated, both in pure footballing terms and as an important moment of renewed optimism in the post-war period. Few others around the world, though, shared their joy.

(Top picture: Getty Images, design Eamonn Dalton)