While she can never know exactly what caused her cancer, Lucie Morris-Marr said that as she researched the link with processed meats, she got ‘incredibly angry’

In 2022, the investigative journalist Lucie Morris-Marr was in an intensive care unit, recovering from a 12 hour liver resection – a potentially curative treatment. Three years earlier she had been diagnosed with bowel cancer (also known as colorectal or colon cancer), which had since spread to her liver, and the operation had been gruelling.

As she came to in her hospital bed, she saw a sandwich on the tray next to her, “white bread with the cheapest, thin ham in a plastic packet. You see them everywhere, especially in hospitals and school canteens”.

After requesting to meet the hospital catering manager, she asked him if he knew that processed meat was linked to bowel cancer by the World Health Organization (WHO). He didn’t.

“I told him ‘that’s why I’m here’.”

Lucie Morris-Marr, mid-treatment in hospital in Australia

Lucie Morris-Marr, mid-treatment in hospital in Australia

When Lucie was 44, she had just had her first book published about child sex abuse in the Catholic Church in Australia, and was set to go off on a big book tour. “I was really in the prime of my life, and then I got this terrible diagnosis of stage IV bowel cancer.” She had initially been misdiagnosed with diverticulosis and got a colonoscopy (and cancer diagnosis) a year after she initially reported pain.

With her tour cancelled and life turned upside down, she found herself with time on her hands. And when she ran through common causes of bowel cancer, she couldn’t see any clear link. She was under 50 (making this young-onset bowel cancer); had no close relatives with bowel cancer, or any genetic risk; was not obese and ate a diet high in fibre and low in UPFs; never smoked and only drank about once a week.

A biopsy early after her diagnosis confirmed her cancer was ‘KRAS wild-type’, meaning there was no mutation or inherited condition to blame. And so she dug deeper into other possible links.

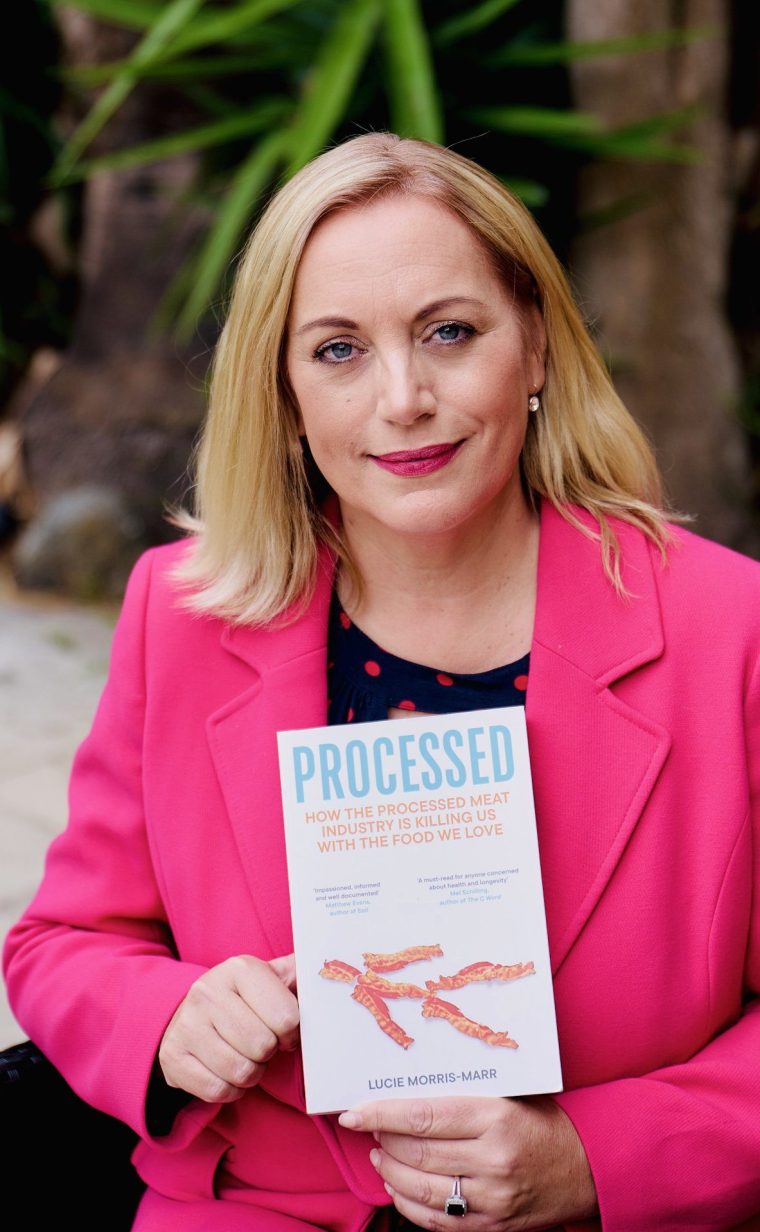

“To my horror,” she writes in her new book Processed: How the Processed Meat Industry Is Killing Us with the Food We Love, “I discovered that – according to many scientific studies – if you regularly eat red and processed meats, such as frankfurts [sic], bacon and salami, you are risking your health and your life. There is a strong bowel cancer link, and other suspected health impacts, particularly with processed meats.”

While she didn’t think she ate processed meats excessively, she began to wonder if the fact they were such a regular part of her diet may have been a factor in her current diagnosis. She ate them probably once a week, fed them to her kids, and loved a Christmas ham.

“I’ll never know if processed meats caused my cancer. No one can know precisely with most cancers. But as I did my reading, processed meats were mentioned more and more, and I started to really focus on it. And I got incredibly angry.”

What are the health risks of processed meat?

Processed meats are a category of animal products that have been modified through a range of methods: curing, salting, fermenting, and smoking. This spans hams, salamis, bacon, sausages and hot dogs, but can also include white and red meat that is processed for nuggets or pies. If the meat percentage is about 50 per cent or less, that means it’s processed.

Over the years there have been several damning studies into how processed meat affects our health.

In 2013, the Global Burden of Disease project found that 644,000 deaths in that year (caused by heart disease, diabetes, and various cancers) could be put down to a diet high in processed meat. They state that “a reduction in processed meat consumption to less than 20 grams per day per person [equivalent to one slice of ham] would prevent more than three per cent of all deaths”.

In the UK, bowel cancer is the fourth most common cancer, with the number of young-onset cases rising 50 per cent between the 1990s and 2018. “It’s a shocking trend,” said Dr Hyuna Sung of the American Cancer Society, who was involved in the research that found this increase.

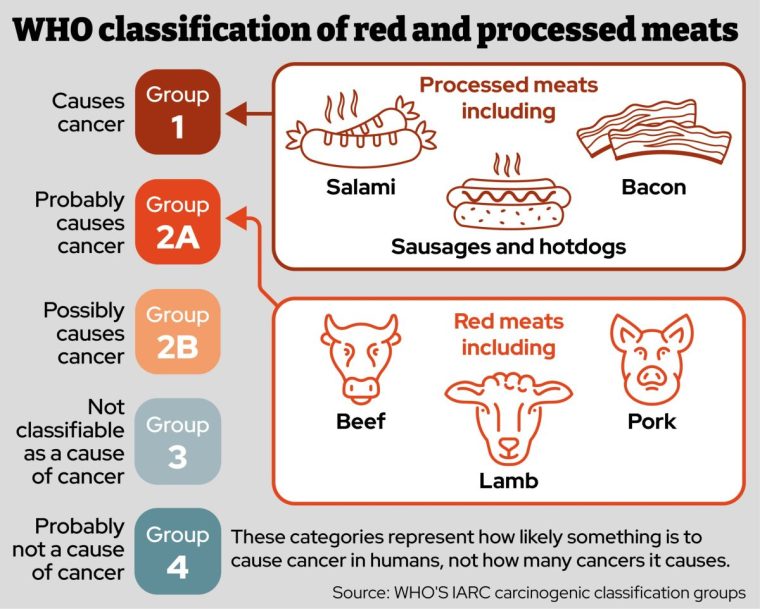

In 2015, there came an even more damning publication from the WHO, whose International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) listed processed meats as ‘carcinogenic to humans’, placing them in Group 1, alongside tobacco, asbestos and radiation.

They concluded eating processed meats like hot dogs, sausages and bacon can cause colorectal cancer in humans, and that red meat is also a likely cause of the disease. They also linked the consumption of red meat with pancreatic and prostate cancers.

The carcinogenic classification of processed and red meat as decided by WHO in 2015

The carcinogenic classification of processed and red meat as decided by WHO in 2015

Crucially, it is the processing of meats in itself that can lead to the formation of harmful substances. On top of that, the chemical preservatives that are added increase their negative health impact.

One of the major targets of Lucie’s ire in her book were those chemicals: specifically nitro-preservatives that are often used in cured meats. These preservatives (sodium or potassium nitrites/nitrates), she explains, are a fundamental building block of the meat industry.

“Nitrates are needed in most processed meats in supermarkets – they make them pink and they stop botulism, which is serious and fatal. They also keep products shelf stable and make them last a long time – they can survive transportation and being in the supermarket and then be in the consumers’ fridge for four to six weeks, perhaps even longer.”

While nitrates themselves are not carcinogenic and can be found in plants, certain waters and in our bodies, certain conditions can cause them to transform. They give rise to free radicals that then react with meat as it’s processed, leading to the production of carcinogenic compounds called N-nitroso compounds. When broken down in the liver, they can damage the DNA of our cells.

“Scientists think they can start those cancerous polyps,” Lucie says, “and as I found out through the book, it can also create an environment for all these other things, it’s really shocking.” By the end of her book she has found research that sees links between processed meats and: breast cancers, upper GI cancers (including pancreatic, stomach and oesophagus), renal (kidney) cancers and diseases, heart disease, obesity, leukaemia, Type 2 diabetes, mental health disorders, and dementia.

The majority of processed meats will use nitrates, though there are a few brands available in supermarkets (like Naked and Finnebrogues in the UK) that are nitrate-free. There has been some exploration into using alternatives like celery powder, but these haven’t taken off because some countries won’t import them as they’re unsure of the allergy risks.

Unfortunately, the way you cook it also can make processed meats cancerous, irrespective of nitrates.

When meat is browned or charred, it can form potential carginogens. “Fried bacon contains more of the carcinogenic substances called heterocyclic amines (HCAs) than any other cooked meat,” she writes. “It also contains high levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), another group of substances linked to cancer.” The more browning on any meat, the more carcinogenic substances. Grilled or barbecued meat and fish have also been associated with a possible increased risk of stomach cancer.

This extends to smoking meat, too. The smoke forms HCAs as well as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Both are harmful and increase your cancer risk. And the impact of smoking is not reserved for meat – the production of these molecules are also found in smoked fish and cheeses.

To Lucie, the evidence was damaging and its scale overwhelming. She felt a responsibility to amplify this information in the hope that she could shed light on it.

“If you look on health and advisory pages of these charities’ websites like Cancer UK for example, you’ll see that they nearly all say to eliminate or reduce processed meat. But because their audience has already got cancer or they are caring for someone with cancer, it’s not reaching a wider audience. Where’s the government health campaign? Where’s the labelling?”

She’s found that often, people don’t want to think about processed meat in the same way we now think about cigarettes. Part of the problem, she argues, is that every country will have processed meat embedded into their culture. She has lived in Australia for the past 18 years where the ‘sausage sizzle’ is ingrained; over here in the UK, the most common snack made during the pandemic was a bacon sandwich.

She says that that’s why for every friend who has said they’ve changed their shopping habits, she’s also had someone (often friends’ husbands) push back, saying ‘we need meat’ and ‘we need the protein’.

“There’s this idea that ‘everything causes cancer’, which I get a lot. Often it’s men pushing back and it’s quite defensive. I did all that work on the Catholic child abuse scandal and I felt like this was bigger. It’s a very touchy subject for people.”

Lucie with her new book, Processed (Photo: Lauren Sadler)

Lucie with her new book, Processed (Photo: Lauren Sadler)

Lucie says her intention is not to tell people what they should and should not eat.

She wants to ensure people know about the signs of bowel cancer (abdominal cramping, weight changes, bloating, or any changes in your poo) as well as how their lifestyle could contribute to it.

In the meantime, she herself has completely changed her relationship with meat, particularly processed, as she has had an opportunity that many of her fellow bowel cancer friends haven’t.

A few weeks before she hit five years since diagnosis, Lucie had a liver transplant – the third person ever in Australia to have one as a metastatic bowel cancer patient.

“While the liver transplant was successful, I have had a lot of complications,” she says. “It’s been a very difficult recovery, really challenging. Still, I have been cured of cancer and if the cancer had spread I’d be in palliative care, or worse.”

Now she only eats meat on specific occasions.

“I’m probably 95 per cent vegetarian, but I love a bit of salmon, free range chicken, very rarely a grass-fed steak when I have low iron and it’s recommended by dietitians. And I try to have the best quality I can.”

With her family, she knows her son and daughter will have the occasional pepperoni on a pizza with friends, which she doesn’t mind, but other than that it’s a no-go.

In her case, she has all but cut processed meat from her life. But even now, she confesses, she has one small, organic and nitrate-free pig in a blanket every Christmas to remind her of England. “There’s something about cured meats that are so delicious. A bacon sandwich would be my last meal on death row.”