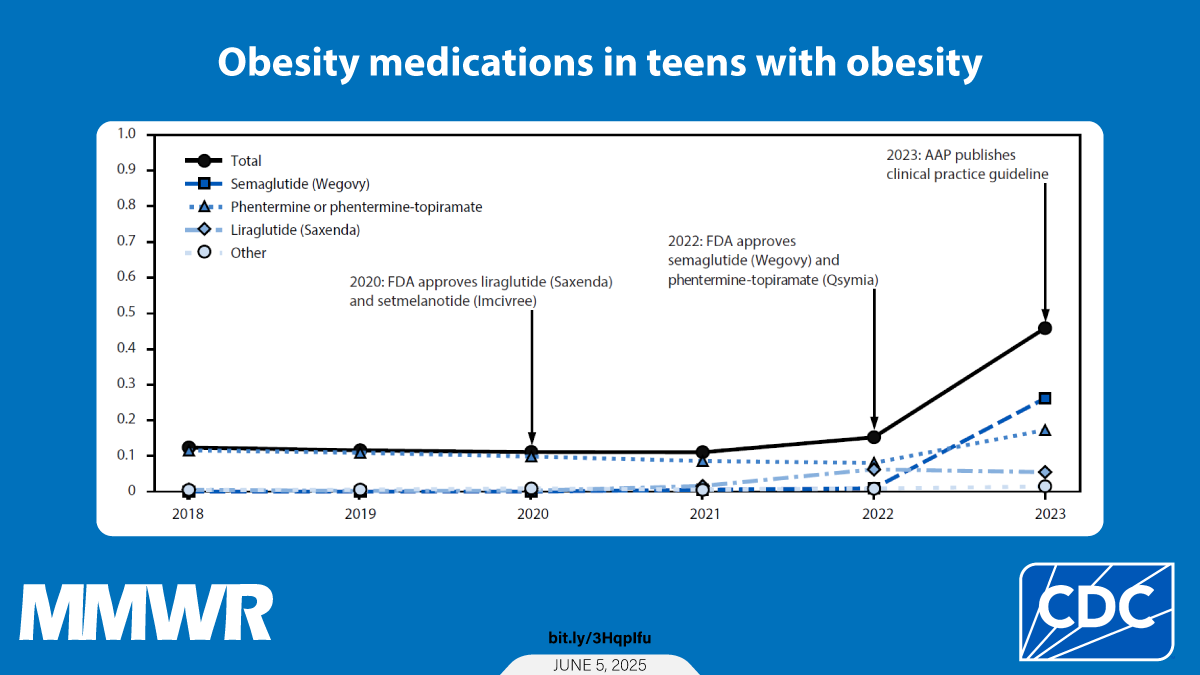

This pharmacoepidemiologic study using a large ambulatory EMR database detected a substantial relative increase (approximately 300%) in the proportion of U.S. adolescents with obesity who were prescribed an obesity medication in 2023, which was the year after FDA expanded its approval of two obesity medications to include adolescents††† and after publication of the AAP clinical practice guideline in January 2023 (1). Despite this substantial relative increase,

A recent study reporting prescriptions filled from 93.6% of U.S. retail pharmacies showed an approximate 500%–590% increase in the dispensing of GLP-1RAs to adolescents aged 12–17 years between 2020 and 2023 (2). This report, which focuses on prescribing of FDA-approved obesity medications, including 2 GLP-1RAs, for adolescents, demonstrated a lower but still substantial (approximately 300%) increase, indicating rising use of multiple classes of obesity medications. A recent study also reported an increase in prescribing of FDA-approved and off-label medications among children and adolescents with obesity after publication of the AAP clinical practice guideline in 2023 (3). Given this increase in prescriptions, postmarketing monitoring is essential to track potential increases in unanticipated side effects or adverse events associated with the use of these medications (4). Because of recent GLP-1RA shortages, safety concerns also might arise for persons filling prescriptions with counterfeit medications or compounded medications (formulations that are created for specific patients or settings, rather than for commercial distribution, and that are not FDA approved); the safety, effectiveness, and quality of these products are not evaluated by FDA before dispensation to the patient (5).§§§ All adolescents with obesity, including those who receive obesity medications, should receive evidence-based health behavior and lifestyle interventions, which can help them and their families build skills that promote healthier nutrition, physical activity, and related behaviors; lower their health risk; and improve quality of life and self-esteem (1).¶¶¶ This study could not elicit data on whether adolescents were also receiving these recommended interventions. Public health and health care organizations might need to assess their capacity and readiness to provide these evidence-based interventions to the millions of U.S. children and families who need them.

Semaglutide indicated for persons aged ≥12 years with obesity (Wegovy) and phentermine or phentermine-topiramate were the most prescribed obesity medications in 2023. The oral administration, lower out-of-pocket costs, and more consistent availability of phentermine or phentermine-topiramate (compared with semaglutide, which is administered by weekly subcutaneous injections) might be factors in the increased use among adolescents in 2023 compared with previous years (6).

This study excluded medications that were not FDA approved for obesity treatment in adolescents but are often used off-label for this purpose (e.g., metformin, semaglutide [Ozempic], and liraglutide [Victoza], all indicated for persons with T2DM). A sensitivity analysis including semaglutide and liraglutide regardless of indication resulted in a slightly higher prescription prevalence (0.7% in 2023). Future analyses could focus on medications prescribed off-label for obesity or for other conditions that also help with weight management.

The findings in this report indicate that health care providers tended to prescribe obesity medications to adolescents with severe obesity. Approximately 83% of adolescents who received an obesity medication prescription had severe obesity (class 2 or 3), including 52% with class 3 obesity. Higher obesity class is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk, lower health-related quality of life, and declines in physical function (7,8), which might prompt providers to prescribe obesity medications to this population.

Prescribing of obesity medications also differed by sex, race, and U.S. Census Bureau region. Girls were more likely than boys to be prescribed obesity medications. In addition, although the prevalence of severe obesity among Black adolescents was 27% higher than among White adolescents, Black adolescents were 39% less likely than White adolescents to receive an obesity medication prescription. Factors that might explain differences in prescribing or low prescription rates include limited availability of the medications because of production shortages (9), high out-of-pocket costs (6), and insurance restrictions, such as lack of coverage or complex prior authorization processes.**** In addition, concerns among adolescents and health care providers about long-term use and safety, as well as health care provider knowledge and self-efficacy in prescribing obesity medications, could impact prescription rates (10).

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least five limitations. First, although this analysis included a geographically diverse sample of health care–seeking adolescents with measured height and weight, the sample was not representative of all U.S. adolescents; this analysis should be replicated with other datasets, particularly those that are population based. Second, although prescriptions documented in ambulatory EMR data were able to be tracked, some prescriptions might have been provided in outpatient visits that were not captured in this database. Third, although prescribing behaviors were tracked, information about whether the medications were dispensed or used was not available. Fourth, missing data on race and ethnicity limited the ability to examine differences in obesity medication prescribing. Finally, this analysis did not adjust for household income, insurance status, or other factors that might be associated with receiving an obesity medication prescription.

Implications for Public Health Practice

Despite the increasing proportion of adolescents with obesity who were prescribed an obesity medication from 2018 to 2023,