Europe is changing, and fast. For the world’s most persuasive normative superpower, the European Union (EU), the age of peace evangelism is now history. Europe is changing so fast that conversations in certain European capitals have become unrecognisable when compared to just four months ago, before US President Donald Trump’s second term began. Europe, of Metternich and Machiavelli, is going back to its realpolitik roots. Formally ushering in this change, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen unveiled an €800-billion project in early March: “We are in an era of rearmament.”

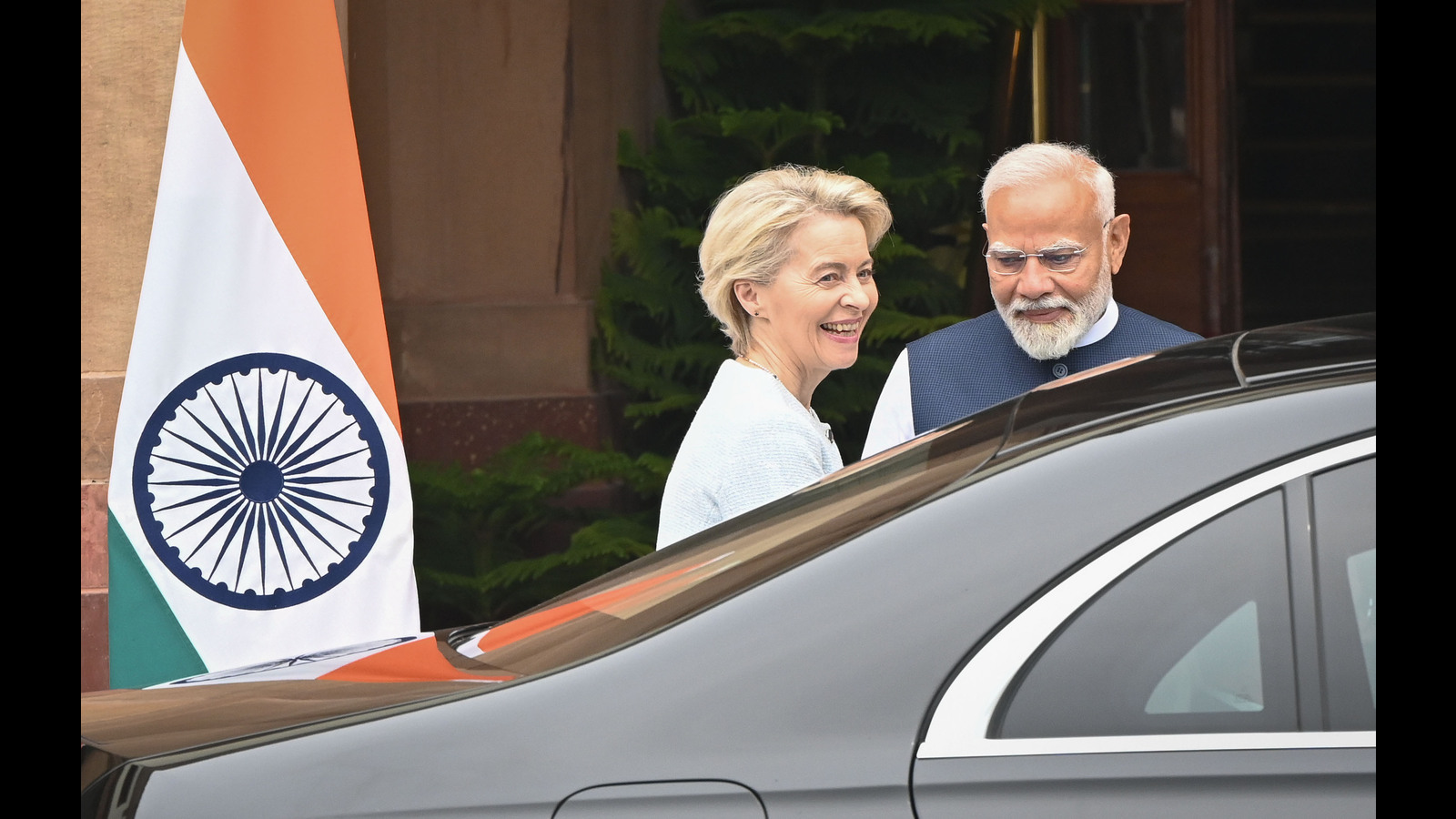

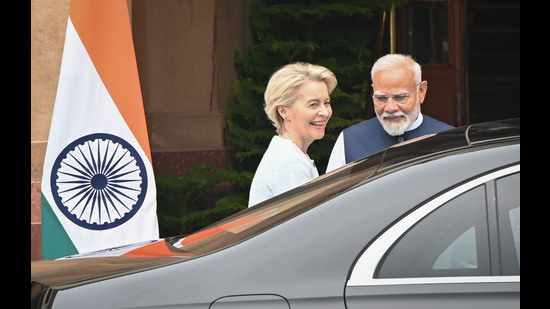

New Europe’s demographic challenges and rearmament requirements will need partners such as India for joint defence production, ammunition, and skilled, cheaper labour (Hindustan Times)

New Europe’s demographic challenges and rearmament requirements will need partners such as India for joint defence production, ammunition, and skilled, cheaper labour (Hindustan Times)

Later last month, von der Leyen further explained what European rearmament means: “The era of the peace dividend is long gone. The security architecture that we relied on can no longer be taken for granted. Europe is ready to step up. We must invest in defence, strengthen our capabilities, and take a proactive approach to security. We are taking decisive action, presenting a roadmap for ‘Readiness 2030’, with increased defence spending, important investments in European defence industrial capabilities.”

It appears that Europe’s post-national experiment was unsustainable in a world of nation-States vying for power. If it took Vladimir Putin to recall Europe from its geopolitical vacation, Trump’s America is getting Europe to work (read ReArm).

The EU’s quest to become a major security and defence player could help usher in a multipolar world order, quite inadvertently so. Consider this. What is missing from the current discussions on multipolarity is a European candidate (notwithstanding the French claim to be a pole). Caught between a revisionist Russia and an untrustworthy US, and stripped of its decades-old geopolitical comfort, Europe is re-arming itself. If it succeeds, the EU will be a top global power. Even if it falls short, Europe will still be a major geopolitical player. Either way, a militarily strong EU will be one of the most important poles in a multipolar world.

In fact, Europe’s rearmament could help create a multipolar world, countering the current trend towards an EU-China bipolar system. Even if the EU itself doesn’t become a pole in the classical sense, there might emerge militarily and economically strong States within the EU which might be considered as poles. EU’s military buildup could disrupt the US-China bipolar trend, potentially creating a multipolar world. New Delhi has reasons to be delighted. This is clearly something it would welcome given its own “pole ambitions” in a multipolar world.

Europe’s deep economic relationship with China has traditionally dictated its China policy; and its military weakness discouraged any confrontation even if it wanted to stand up to China. But now a militarily self-confident Europe could be less accommodating of China’s aggression on the world stage. While New Delhi shouldn’t hope to see friction between Brussels and Beijing, such a development would surely be welcome here.

What strikes you most about today’s Europe is that it is willing to have more honest conversations about the harsh realities of geopolitics around us, from Brussels to Berlin to Warsaw. But conversations apart, when a $20-trillion economy with 450 million people makes life choices, it is bound to have implications for the rest of the world.

A re-armed Europe will also fundamentally alter India’s view of the EU. Over the past two and a half decades, India’s relations with the US have transformed. But its relationships with Brussels or other major European capitals have continued to be challenging. In the past, India’s geopolitical initiatives were often frustrated by Europe’s normative hang-ups, and New Delhi’s desire to behave like a ‘normal’ state in the international system were moderated by Europeans. It may not be the case anymore. Going forward, trans-Atlantic tensions and Europe’s return to classical geopolitics will mean India will have more options on the table.

New Europe’s demographic challenges and rearmament requirements will need partners such as India for joint defence production, ammunition, and skilled, cheaper labour.

Both India and the EU place a great deal of importance on strategic autonomy, but they have both — the former more so than the latter — realised that over time that desire for strategic autonomy without military muscle is political grandstanding. Rearmament of Europe and its search for strategic autonomy from the US will be another important factor that could bring India and Europe together.

Then, there is the issue of trust. When contemporary Europe looks around, it sees very few nations it can trust for partnership: Russia is aggressive, the US disinterested, and Japan and South Korea worried about their own security considering the doubtful state of American security guarantees. This is where New Delhi comes in, as a defence partner, as a pivotal State in the Indo-Pacific, as a huge market, and a potential partner to create a new world order.

“Trust,” said EU ambassador to India Hervé Delphin at the Carnegie Global Tech Summit, “is now a critical raw material of geopolitics, with unprecedented value. This will define the dynamics of the emerging world. EU rearmament is enabling us to realign partnerships faster, especially with India.”

For India, there has never been a better time to do business with Europe — more forthcoming, less judgmental, wanting to talk about global governance, values and defence all at the same time.

Happymon Jacob teaches India’s foreign policy at JNU, and is editor, INDIA’S WORLD. The views expressed are personal