We are all familiar with the challenge of ‘hitting the ground running’. Imagine trying to hit the ground painting – while you are being jostled by crowds, keeping a frantic eye on the clock and, all the while, having that same nagging thought at the back of your mind: this had better be really good. Oh, and make sure you look smart, too.

Over 40 years, that has been the challenge facing some of our most talented – and most fortunate – artists. They are the ones who have been chosen to join King Charles III (in some cases as monarch, in others as Prince of Wales) on a royal tour as his official tour artist.

Between them all – there have been 43 of them – they have produced a richly varied collection of oils, watercolours and even sculptures chronicling the globetrotting of the most widely travelled monarch in British history. Now, to mark four decades of this accumulated high-speed artistic endeavour, some of the finest works have been put into a handsome and intriguing new book.

The Art Of Royal Travel: Journeys With The King is not just a visual treat. It is a cracking read, too, capturing the glamour, the mayhem, the hilarity, the glitches, the soft power, the heavy protocol and also the surprising informality of life on the road with our King. Full of delicious vignettes, it takes us far beyond the red carpet. We discover what happens when you are doing your job one minute only to be mistaken for a potential spy the next; the omnipresent fear of being separated from the royal entourage – and what you do when it actually happens; the perils of falling ill; an actual case of ‘the dog ate my homework’; and what happens if your royal patron decides to pick up his own brush and join you.

Then Prince of Wales and Duchess of Cornwall, Charles and Camilla visit the Grand Mosque on the first day of a royal tour of the United Arab Emirates in November 2016

What also emerges throughout is the ‘pinch me’ sense of appreciation all these artists feel after an experience that, in many cases, changed their lives and careers. Though all were professional artists already, many went on to greater things. Claudette Johnson, for example, was later nominated for the Turner Prize. It also left them with a fresh perspective on royal diplomacy. ‘What the prince did on this tour was an inspiration,’ says Tom Hallifax, looking back on the 1994 visit to Los Angeles and Hong Kong. ‘His presence alone made a difference – giving people attention is a very powerful thing to be able to do.’

The idea of travelling with an artist is not new. As the book’s editor, the Earl of Rosslyn (Lord Steward of The Household and Personal Secretary to The King and Queen), explains in his introduction, Queen Victoria liked to have a painter on hand to record her tours and would often paste the results into what she called ‘Souvenir Albums’. The late Duke of Edinburgh invited the distinguished artist Edward Seago to join him for some of his epic 1956-7 round-the-world voyage on the Royal Yacht, Britannia.

In the duke’s case, he also wanted to watch Seago at work and learn how to paint himself. The results were impressive and ended up on the walls of various royal residences, which may be why a young Prince Charles decided to start painting himself. Unlike his father, who painted in oils, his preferred medium would always be watercolours.

Ahead of the 1985 royal tour of Italy, the prince decided he wanted to bring an artist with him. After all, the Royal Yacht would be sailing into Venice, a city the prince had come to adore through Windsor Castle’s unrivalled collection of Canalettos. So he invited John Ward to join the party. A leading artist of his day, Ward was just the man. He had painted members of the Royal Family, as well as the 1981 wedding of the prince to Lady Diana Spencer, plus portraits of Princes William and Harry. He spent much of his time on the decks of Britannia capturing the essence of the tour, and whenever the prince was able to steal a few off-duty moments he would join Ward and do some painting too.

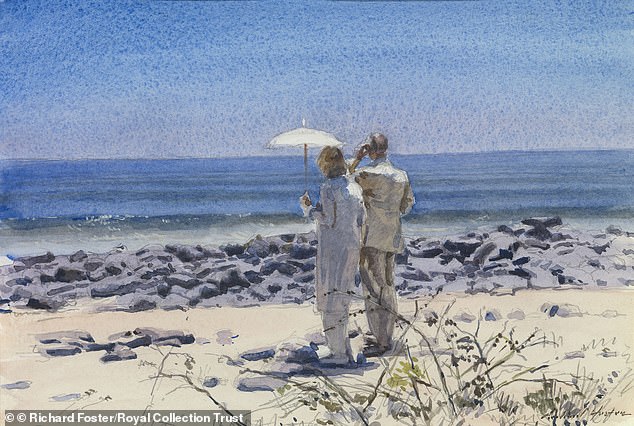

A miscommunication meant artist Richard Foster missed the boat for a royal excursion to the uninhabited North Seymour Island. Fortunately the coastguard got him there in time to paint this watercolour of Charles and Camilla

Royal tours, though, are neither for pleasure nor leisure. They are a hectic exercise in diplomacy and flying the flag, yet as a painter himself, the prince longed to see them through an artist’s eye. As he later reflected, ‘You discover much more than pointing a camera.’ So, he decided that, whenever possible, he would bring an artist with him. And that is what he has been doing ever since, always with the same conditions: it is entirely up to the artist where, what and how they paint, the King will cover all their expenses from his own pocket, and don’t be late for the royal plane or convoy. Because it will not wait. In return, the King likes to choose a single piece of work from whatever emerges for his collection. The artist can keep or sell the rest as they wish (if the King wants any further pieces, he will pay for them).

No one applies to be a royal tour artist. They are usually recommended by one of the King’s many contacts in the art world or else he will have spotted their work. In recent years, Queen Camilla has played a part in choosing them, too. They usually receive a call or email that many instantly think is a prank. ‘I thought it was a wind-up from one of my friends, as something like this was not likely to happen to someone living in Kalamunda,’ recalled Godfrey Blow, a British painter based in the Australian town. He ignored several further emails until he received a request for a meeting with officials from the Palace. It was no joke. He really was being asked to paint the Western Australian section of the 2015 royal tour Down Under.

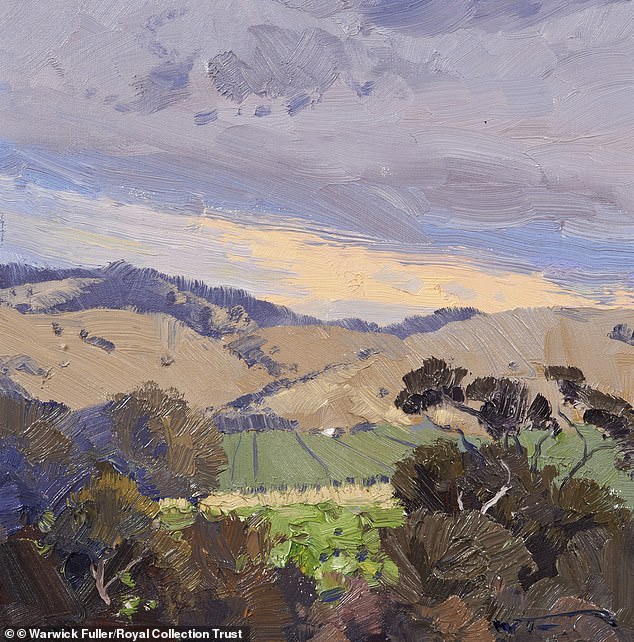

Warwick Fuller was in the Barossa Valley, Australia in 2012 with the royal couple

Fuller’s painting of the Barossa Valley vineyards three years later

Kiwi Ben Woollcombe very nearly ruined his own chances of joining the New Zealand leg of the same tour. When the call came through to his mobile phone, he saw it was a London number and blocked it to avoid a hefty international call charge. Fortunately, the prince’s team were persistent.

Having accepted an invitation, the next issue is what to wear? All artists need to look reasonably smart. Alexander Creswell asked a tailor friend to make him a suit before the 1998 tour of the Balkans. New Zealand’s Sue Wild sewed herself a ‘splendid mobile sketcher’s pinny with pockets for small palette, brushes, pens, pencils, camera and even water’.

Martin Yeoman, one of the earliest members of this exalted club, remembers going to a charity shop to buy himself a 1950s suit ahead of the prince’s 1986 tour of the Middle East. Even then, it didn’t convince everyone on the journey through Oman and Qatar to Saudi Arabia. Sitting outside a police station sketching a man with a wheelbarrow, he was arrested for being a spy. ‘When the press arrived with their huge cameras, no one batted an eyelid,’ he recalls. ‘People were more suspicious of me sitting quietly with my pencil.’

Susannah Fiennes painted the Prince of Wales sitting with his watercolours

Their royal patron would always go out of his way to stress that, as artists, they had total freedom. He was well aware of the pressures of the travelling circus on an old pro like himself, let alone a newcomer. William Rogers, an accomplished watercolourist from Nova Scotia, was touched when, in the middle of a busy day on the 2014 tour of Canada, Prince Charles took him aside ‘to tell me that I should paint whatever I wanted – there were no expectations for any subject or style’.

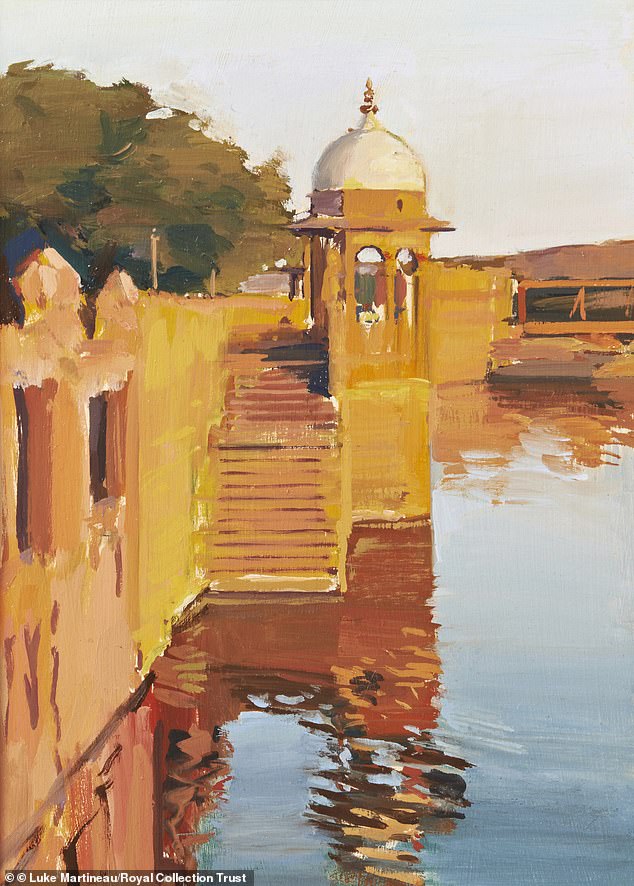

However, that did not stop the royal patron from making occasional suggestions, as Luke Martineau discovered when he was the artist on the 2010 tour of India. He was hard at work at the Bal Samand Palace near Jodhpur when a member of the royal team ran up to tell him that the prince was very keen that he should see the sun setting over the lake. ‘I breathed a huge sigh of relief,’ says Martineau, ‘that I was already painting that very thing.’

In India in 2010, the Prince of Wales sent an aide to urge artist Luke Martineau to catch the sunset at Bal Samand Palace. Martineau said: ‘I breathed a huge sigh of relief that I was painting that very thing.’

Prince Charles and the Duchess of Cornwall with Punjab state public relations minister Sewa Sekh ahead of the opening ceremony of New Delhi’s Commonwealth Games in 2010

Emma Sergeant was on the last leg of Prince Charles’s exotic and historic 1996 tour of Ukraine and Central Asia, the first time a senior royal had set foot in these places. The prince was visiting a tea house in Uzbekistan, a place where weary travellers would rest on the Silk Road trade route. ‘In the tea house, there were lots of elderly men sitting around in their brightly coloured chapan robes with long sleeves,’ Sergeant recalls. ‘The prince said to me, “Don’t miss the one in purple,” so I stayed behind and did a quick drawing in about five minutes, with the cars outside revving their engines, ready to rush us to the airport.’

She was lucky that they didn’t set off without her. It had nearly happened the previous year when she had been asked to capture the prince’s tour of Morocco and found herself entranced by a market scene in a souk. ‘Suddenly I looked up, and the party had moved on. There were lots of narrow streets converging, and I didn’t know which way to go. Luckily, because I was smartly dressed, everyone pointed me in the direction of the royal party and I ran and finally caught up with them.’

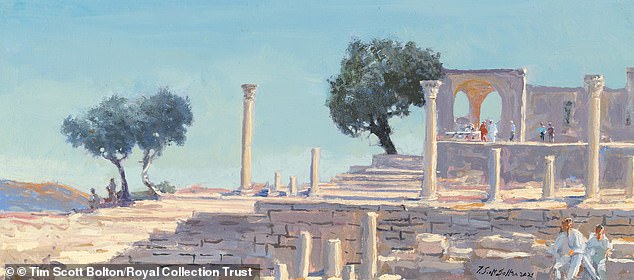

Poor Tim Scott Bolton was less fortunate during the 2021 tour of Egypt. Having arrived at Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque, he spent so long working out the composition for his painting that he took his eye off the clock and the royal convoy set off for the pyramids of Giza without him. The problem with losing the entourage is not only that you then have to catch up without the benefit of outriders and blue flashing lights. It can also be nigh on impossible to break through the security cordon and get back inside the royal bubble.

Tim Scott Bolton’s painting of the Roman site of Umm Qals in Jordan

Charles and Camilla visited the site, near the Sea of Galilee, in 2021

That was Scott Bolton’s fate when he finally reached Giza. Rather than panic, he found a crowded café with a rooftop view of the Sphinx and started making up for lost time. ‘When I was packing up,’ he remembers, ‘I put my painting down on the floor momentarily, and someone promptly stood on it! So that painting still has a very clear footprint across it.’

He has happier memories of joining the prince in 2017 for the royal tour of Italy. Not only did it coincide with his 70th birthday but he accompanied the prince to meet Pope Francis. ‘It must be one of the highlights of anyone’s life to meet the Pope, but I am still haunted by the thought of whether I got it wrong. When I was introduced as the tour artist, the Pope turned to the prince and said, “I thought you were the artist,” to which the prince replied, “He paints better.” I immediately responded, “I disagree,” before being overcome with embarrassment that I should have dared to contradict the Prince of Wales in the presence of the Pope.’ The fact that Scott Bolton was asked back twice more would suggest that no one was bothered.

The most prolific of all the tour artists is Peter Kuhfeld. Having previously been commissioned to paint the prince’s sons, he went on his first tour, to Africa, in 1990 and was still being asked back 33 years later to paint the 2023 state visit to France. This involved two added challenges. First, he had forgotten his braces and arrived at the black tie banquet at Versailles holding his painting kit in one hand and holding his trousers up with the other. Next, his painting position turned out to be in the flightpath of all the waiters.

None of this was as challenging as his trip into the desert with the Prince of Wales in 2004. Entranced by the blueness of the sky in the heat, he neglected to cover up and went down with sunstroke. The royal doctor sent him to bed to sweat it out beneath layers of blankets. The next day, he awoke to find a very smart trunk outside his tent with the Saudi royal crest. Inside was a beautiful farwa (coat), lined with lambswool and made extra-long to be worn in the desert.

Weather has always been an issue. Devouring this book, I particularly liked Warwick Fuller’s powerful paintings from Australia and Samoa with minutes to go before serious storms burst over him. As he reflects, ‘I painted it fast and furious, as the rolling clouds were goading me.’

Stories like these accompany each set of paintings in a series of engaging pen portraits by the book’s authors, Theresa-Mary Morton and Helen Rosslyn. Some are hilarious, like Mary Anne Aytoun Ellis’s memory of the 2001 tour of Canada. Aytoun Ellis liked to paint in tempera, which involves mixing pigment with egg yolk. She had been keen to divert from the royal itinerary for a few hours to capture a dramatic ‘buffalo jump’ – a cliff over which indigenous hunters used to drive the animals to their deaths – and had secured half a dozen eggs from the royal chef. Having been led to the perfect spot by her guide, she suddenly heard a loud crunch. They both turned round to find that the guide’s labrador had eaten the eggs. She had also brought some watercolours but the dog had knocked over the water, too. ‘In the end, I had to use lager,’ she says.

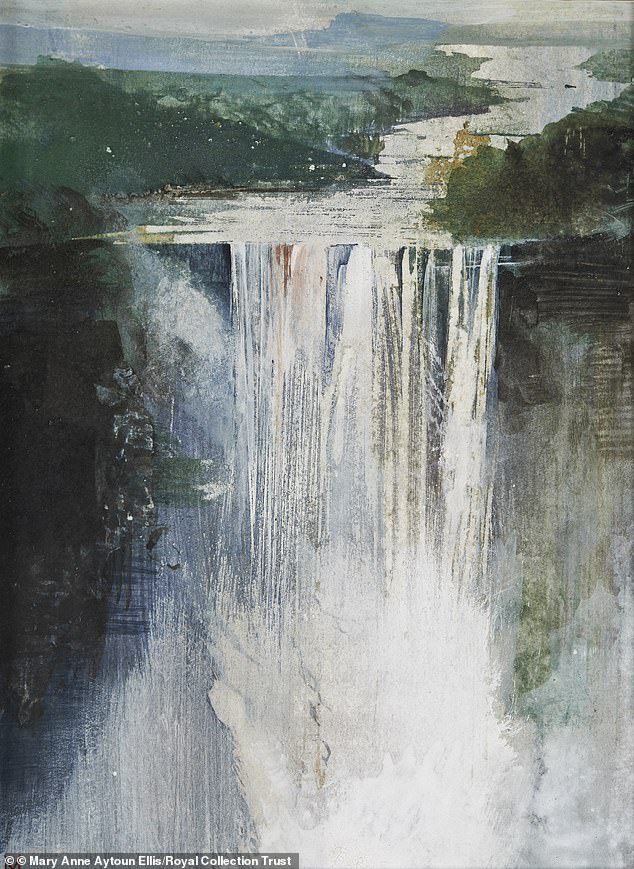

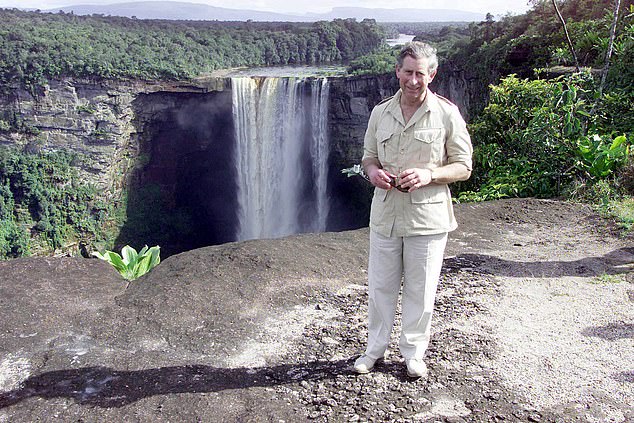

Mary Anne Aytoun Ellis painted the Kaieteur Falls in Guyana

Prince Charles visited the spectacular spot in 2000. Kaieteur Falls is the highest continuous single drop waterfall in the world

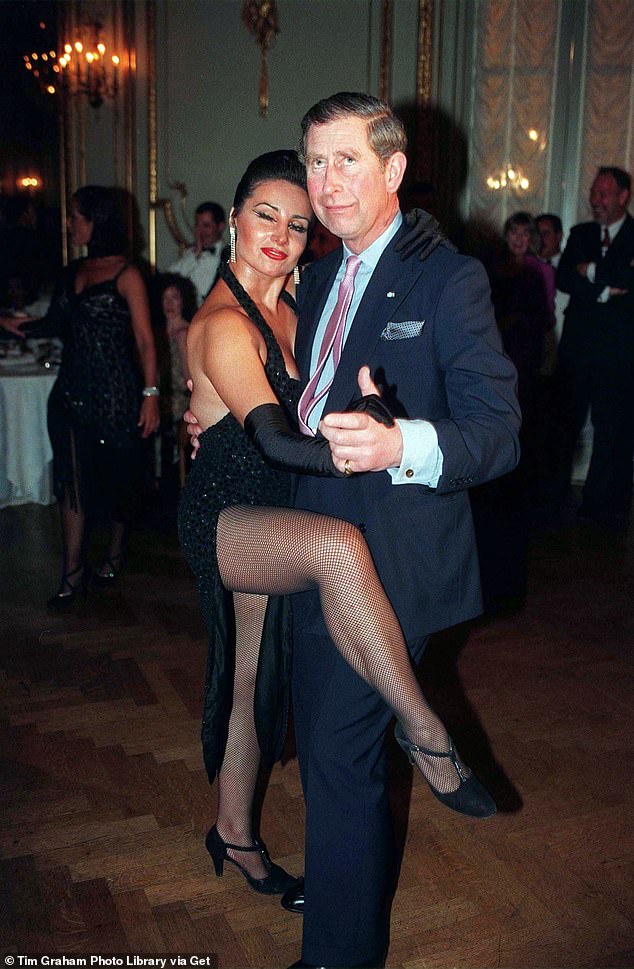

What I find so captivating about this book is that, on many of these tours, I was there too working as a royal correspondent. And just one look at, say, Susannah Fiennes’s watercolour of the Royal Yacht against the Hong Kong skyline ahead of the 1997 handover, or her sensuous oil of tango dancers during the 1999 tour of Argentina brings it all back in an instant. Looking at Toby Ward’s painting of the Prince of Wales being interviewed on a Saudi sand dune in 1993, I recognise this straight away as a scene from his famous 1994 ITV documentary.

Susanna Fiennes painted this atmospheric portrait of the Prince of Wales dancing

The painting was inspired by the prince’s tango with professional Argentine dancer Adriana Vasile at the president’s dinner in Buenos Aires in 1999

Susannah Fiennes has worked extensively with the King as a royal tour artist

We in the press pack would often look at the official artist and wonder how on earth anyone could craft anything on canvas out of the happy chaos that characterises the average tour. Yes, you get to see the best of everything but it is normally for about 30 minutes before it’s a dash back to the convoy and on to the next thing.

It was even harder for Marcus Cornish, who was on the 2000 tour of Switzerland and Slovakia. He was not a painter but a sculptor. He gamely brought some clay on the trip, heaving it around in a cabinet. ‘It was quite large, so I fitted a strap to carry it like a rucksack – a mad idea really. I must have looked very odd in a suit with a wooden box on my back. I put a bit of clay in each of the drawers, and my plan was to whip one out and quickly mould a head as we went from place to place.’

After a few attempts it became impossible, so he decided to sketch on the hoof and sculpt later. Yet looking at Cornish’s deft sketch and bust of a proud old Slovakian war veteran, I can instantly recall that old people’s home in Bratislava.

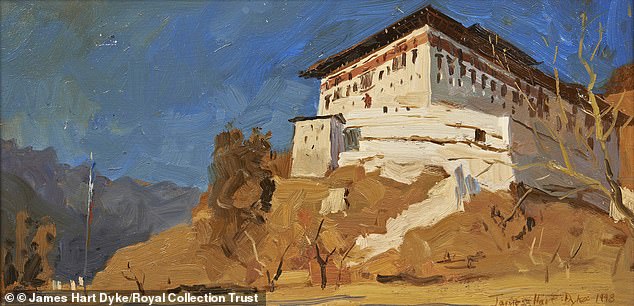

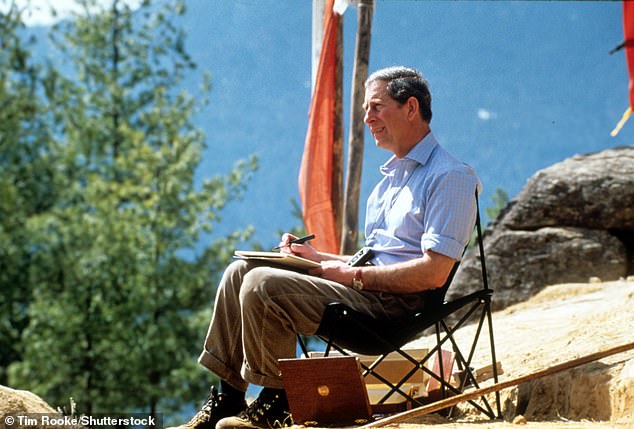

On more exotic tours, the prince would still try to find a little time to paint with some of his artists, like James Hart Dyke, whose breathtaking panoramas of Bhutan (1998) and the mountains of Saudi Arabia (1999) are all the more impressive with the revelation the artist was actually suffering from altitude sickness at the time. He also did some wonderful portraits of his royal patrons and their hosts (my favourite is not even in this book; it is a Hart Dyke pencil and watercolour sketch of a journalist scribbling away during the 1998 tour and it still hangs above my desk, as that scribbler is me).

Artist James Hart Dyke’s oil painting of Paro Dzong Buddhist monastery in the Himalayas

Charles was keen to capture the monastery in watercolour when he visited in 1998

Oil portraits of Charles and Camilla taken from sketches and photos in Kuwait

In rounding up so many talents over so many years, the King has done a great service to British art. There are no pickled sharks or avant garde tat in this book because he has always sought to promote traditional artistic fundamentals like draughtsmanship, drawing, colour and perspective. Some tour artists, such as Tom Hallifax, would return the favour by going on to give lessons at the Royal Drawing School (and Belmarsh Prison, too).

And they all retain a lifelong memory of their trip. Michael J Austin will never forget being joined by the prince, sketchbook in hand, during a trip to a remote corner of Oman. ‘We had sandwiches, rolled our trousers up and waded across the stream. It’s funny, but these memories are so wonderful and warm that I didn’t really want to talk about them afterwards.’

The Art Of Royal Travel: Journeys With The King is published to coincide with the opening of the exhibition The King’s Tour Artists at Buckingham Palace, 10 July, www.rct.uk. All artwork photographs are © Royal Collection Trust.

It is why this book – like the accompanying exhibition which will be the centrepiece of this year’s summer opening of Buckingham Palace – is very much more than an elegant collection of pictures spanning 69 tours and 95 countries across four decades. It is a spectacular, sumptuous portrait of the world – from an utterly unique vantage point.

- The Art Of Royal Travel: Journeys With The King is published to coincide with the opening of the exhibition The King’s Tour Artists at Buckingham Palace, 10 July, www.rct.uk. All artwork photographs are © Royal Collection Trust.