Brexit undoubtedly delivered meaningful wins for animals, enabling policy changes that were previously impossible. We were able, for example, to ban the cruel live export of animals for slaughter and, even more far-reaching, we could change the way we subsidised farming to incentivise higher animal welfare and environmental stewardship.

Neither of these changes could have happened without Brexit, which is one of the reasons I supported our EU exit in 2016.

And although, of course, I wish we had done more, the last Conservative government did deliver a wide range of animal welfare measures – from an expanded ivory ban and banning glue traps, to much bigger sentences for animal cruelty and recognising sentience in law. Now in Opposition, the party is calling for among other things raising zoo standards.

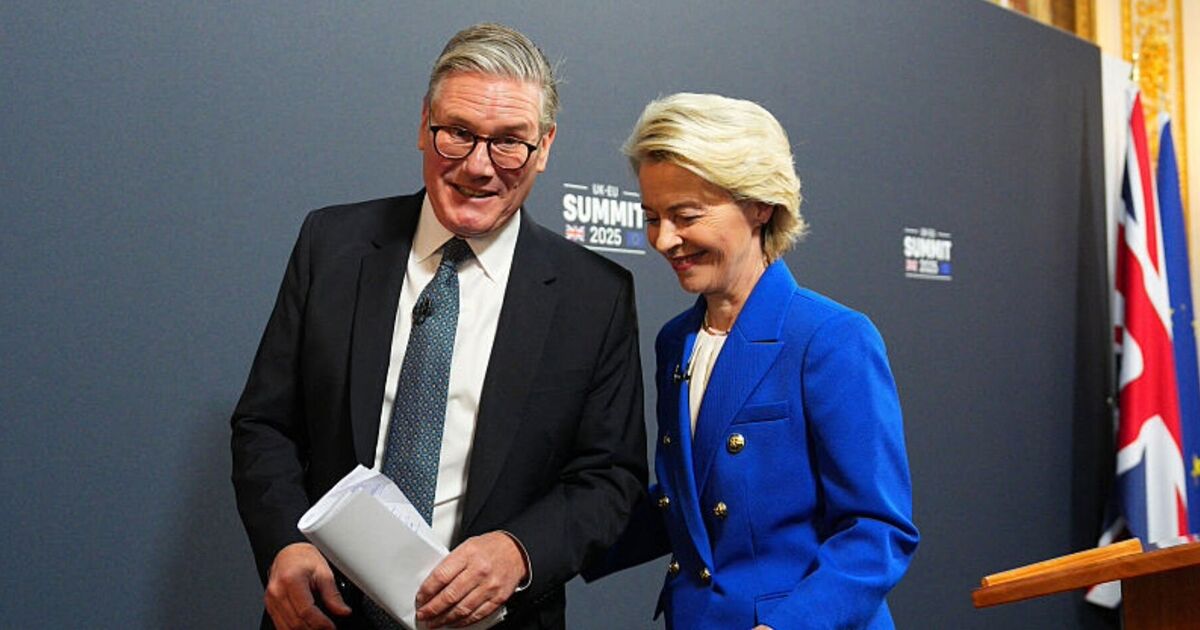

Last month’s UK-EU Summit produced a “Common Understanding” agreement, which has been hailed by the Prime Minister as a significant step towards mending post-Brexit relations, generating economic benefits and streamlining trade. However, buried in the details lies a troubling commitment: any UK deviation from EU food standards must not “negatively affect European Union animals and goods being placed on the market in the United Kingdom”.

This seemingly technical clause has profound implications for animal welfare and our ability to raise our own standards, something we fought so hard to achieve with Brexit. Among other things, it likely means the UK cannot restrict imports of animal products that fail to meet our welfare standards – even when we’ve banned those same practices domestically.

Consider the immediate threats. Around 50% of UK pork imports come from EU countries still using sow stalls – narrow metal cages we banned in the 90s because they were considered to be cruel. The last Labour government prohibited fur farming in the UK, yet we continue importing it from the EU. Under the new agreement, banning such imports may be impossible, despite the stated wishes of the Government to deliver the biggest boost to animal welfare in a generation.

The agreement links UK standards to EU animal welfare rules, with opt-outs limited to public health and biosecurity assessed on a case-by-case basis. So while we might still be able to ban puppy imports, as these present a public health risk, the agreement could block us from banning EU fur or even foie gras on welfare grounds alone.

This not only undermines domestic animal welfare standards but also places British farmers, who adhere to stricter regulations, at a competitive disadvantage.

The problem is more acute with EU imports, our largest trading partner for food imports, not just the usual suspects like the USA or Australia.

Brexit gave us the chance to lead the world on animal welfare – to show that an independent Britain could set gold standards that others would follow. This is also about democratic sovereignty. British voters consistently support higher animal welfare standards, with 84% backing restrictions on low-welfare imports.

There’s still time to put this right, but it will require Government to clarify that animal welfare measures fall outside the SPS Agreement’s scope, or to negotiate explicit exceptions for welfare-based restrictions.

While its proponents say the UK-EU reset agreement offers economic and diplomatic benefits, it’s imperative that animal welfare remains a priority. By addressing these concerns proactively, the UK can position itself as a global leader in animal welfare and ensure that progress is not achieved at the expense of the most vulnerable and the voiceless.