The summer of 1976 was scorching. The West Indies cricket team had spent virtually the entire cricket season in England, facing them in several cities.

At the height of decolonisation, the confrontation was forecasted to be climactic. But the five-match Test series exceeded expectations.

An impulsive comment laced with racial undertones from the England captain. A West Indies side determined to dislodge West Indian cricket from a perceived frivolousness that had stuck, and the series’ tone was set.

The West Indian Team in Australia 1975-6

Clive Lloyd’s team encountered its first major test, facing the champions on their soil in 1975. Australia were feared for their excellent fast bowlers. They desecrated everyone, at home and abroad.

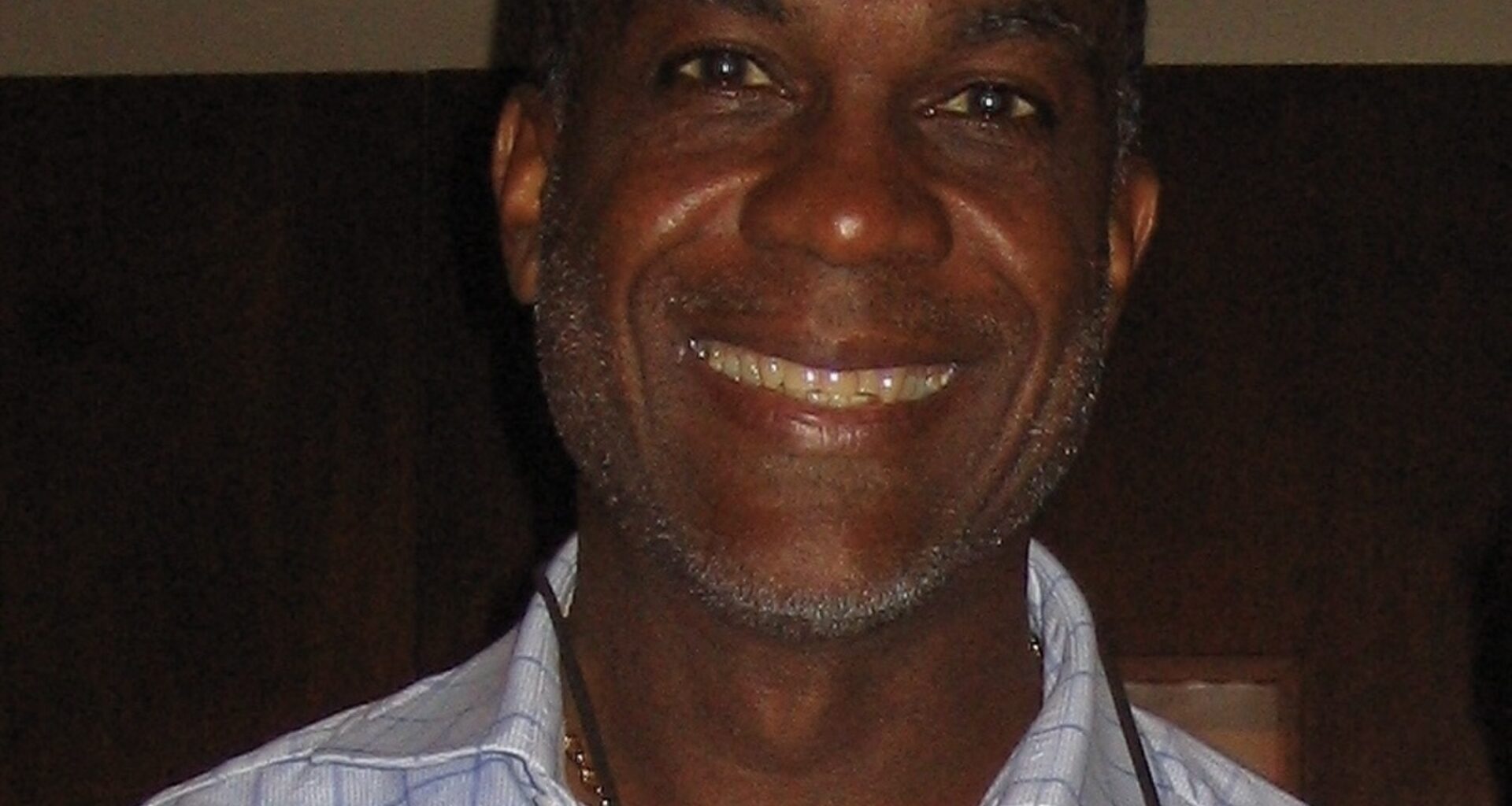

One of the greatest fast bowlers in cricket history, the West Indies’ Michael Holding, remembers the confrontation all too well.

In an exclusive interview with the Sports Gazette, he said: “The most important thing was to not get hurt. Those Australian pitchers were the quickest in the world at the time. I don’t think anything has surpassed them now, anyway.

“Jeff Thompson, in particular, was extremely fast. He was the one that was frightening. They had some outstanding fast bowlers, but Jeff Thompson was the one who was bowling at 100mph. He could hurt you, and he did hurt a few of the West Indies batsmen.”

The Australian players were menacing, but the crowd was relentless.

“When you’re playing in someone’s home town, you expect the crowd to be hostile. You expect that they’ll be cheering for their home team.

“What was a little bit surprising to me, in particular, was some of the abuse that I heard. Some of the things that I heard. People have said and did say at the time that some of it they don’t really mean it. But whatever it was, I just brushed it aside.”

Of six games against the Australians, the West Indies lost five.

The Transformation Of West Indies Cricket

The West Indies side returned home feeling the full weight of their defeat, but Clive Lloyd was no quitter. Determined to repair its reputation and to shed the frivolous label of “calypso cricketers,” Lloyd set about transforming his team.

No stranger to the success of Jeff Thompson and Dennis Lille, the West Indies team committed to the practice of fast bowling. Most teams had two, sometimes three, proficient fast bowlers. The West Indies had four.

With the introduction of a young, hungry Michael Holding into the folds and the presence of Andy Roberts, Vanburn Holder and Wayne Daniel, Lloyd reimagined the West Indian game to one rooted in pace, precision and power.

Intent on proving themselves capable opponents, the team debuted this new technique against India in 1976.

“It was important that we beat India at home because we were then heading to England. The three series were pretty close to each other, and we didn’t really want to be losing two series and heading up to England on the back of that.

“So, it was important that we won that series.”

The Windies won the series two to one after India opted to withdraw their final batsmen in protest of their opponent’s newfound bowling style. Lloyd’s team had little time to dwell on the outcome of the series. England was next.

Tony Greig Resolves to Make The West Indies “Grovel”

On the eve of the first test, England captain Tony Greig was interviewed for the BBC’s Sportsnight programme. Rattled by the coverage highlighting the strength of the West Indies, he responded that he intended to make his opposition “grovel.”

The comment was provocative for several reasons and, coming from a white South African during Apartheid, was latched onto for its racist implications.

“I remember watching it live and seeing the BBC cameras interview Tony Greig down at Sussex,” Holding said. “I’ll never forget the image of when he made that comment about these West Indians, and when they’re on top, they’re a great team, but then he said something about when we get on top of them…no he didn’t say we…I, with the help of Closey and a few others, intend to make them grovel.”

He ran back to inform the rest of the West Indies team of Greig’s promise.

“Immediately, everyone was there saying oh? Okay. Not out loud of course, but in your mind, in your head everyone is saying oh you’re going to make us grovel? Let’s see about that.

“And every time he came into the crease, the fast bowlers just found an extra little pace from somewhere to bowl a little bit quicker at him. We didn’t like the idea that he used that particular term. Tony Greig being a white South African born playing for England because South Africa had been banned for Apartheid, using that term just did not go down well with us.”

Despite its racial implications, pre-series braggadocio was not unheard of. Greig apologised after it became clear that the Caribbean population had not appreciated his comments. But the damage was done. All left was for the England captain to honour his words on the pitch.

The Final Test: Holding Meets Grieg at the Oval

Despite draws at Lord’s and Trent Bridge, the West Indies began dominating the series, and England’s hopes dwindled.

When the final test at The Oval came around, England had launched a recovery. But Michael Holding had other plans. As Grieg came out to bat on Saturday evening, all it took was a couple of cover drives off the West Indies fast bowler, and the England captain was bowled off his pads.

The crowd were jubilant. At once, several hundred spectators, many of West Indian descent, ran onto the pitch and beelined for Greig, taunting him.

Holding did not share the same feeling of euphoria at bowling out Greig as some of the fans.

“It was a satisfying test match, yes,” he said. “But the entire series was satisfying because we pretty much beat England comprehensively. To bowl Tony Greig out, yes, but if you look at that Test match, nothing was bouncing above the stumps, the pitch was so flat that you either got batsmen out bowled or LBW [Leg Before Wicket]. Very few were caught behind because the ball wasn’t carrying that far.

“[Bowling] Tony Greig out that Test was just standard for that particular game.”

Who’s Grovelling Now?

On Monday, Greig strolled towards the open stands situated on the Harleyford Road side of the ground. Defeated, he fell to his knees, grovelling to the crowd who roared in appreciation.

Grovel. Who’s grovelling now?

The following morning, Holding’s 6 for 57 in the second innings earned him 14 wickets in the match.

On the record, Holding is modest in his achievement: “I was 22 years old. I just kept running in and bowling fast and kept on taking wickets. As I’ve said to so many people, yes, 14 wickets is not something that you do every day, I never repeated it, of course, and not too many bowlers get 14 wickets in a test match. But I will never be able to walk around and boast.

“I was just young, quick and whether, in my opinion, was fantastic. Everybody was saying it was hot, if you go back and look at the pictures, you wouldn’t see any sweat on my sweater, so it wasn’t hot for me coming from the Caribbean.

“It was just a fantastic time for me. I was running, everything was clicking, and I just kept on taking wickets. I just kept on bowling.”

West Indies Cricket Refuses To Grovel

The West Indies won the Test series 3-0.

What began as slaves bowling at the leisure of the sons of slave owners became a formidable West Indian team that had come to the motherland and beaten the English at the game they had taken to them. Cricket had become a site that emboldened Black Caribbean people.

“For me personally, it was just a victory,” Holding added, “but for the West Indian cricketers who played cricket in England and for the West Indian fans who lived in England, it meant a great deal more than what it meant to me.

“1976 was my first tour to England. I wasn’t aware of how important it was for the West Indian team to beat England for West Indians living in England. Later on, I got to understand what it meant to them and why they wanted us to win that much.”

After emerging victorious against England, the sport had come to represent all West Indians. Whether in Britain, affected by the racial tensions that defined the mid to late 1900s, liberated from colonial rule or still tied to it. West Indian cricket represented the West Indies’ social resistance and all that came with it.

The Future of West Indian Cricket

Financial restraints, the decline in interest from younger generations, and the growing attachment Caribbeans born overseas have to their national identity have all been proposed as the answer. But perhaps the true answer lies in a truth many hesitate to entertain.

The West Indies cricket team, triumphant in an era defined by social upheaval, was everything it needed to be at that moment.

At present, Caribbeans are scattered across the globe, adapting to a new culture while many of their home nations have been freed from the shackles of colonial rule. As such, the desire to band together against a common enemy in both strength and unity has depleted, and with it, as has their hunger.

Still, this does not detract from the greatness of West Indian cricket. Instead of cowering in the face of their former masters at their own game, the Windies towered over the rest.

In the face of racial and colonial adversity, West Indian cricket had refused to grovel.