This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

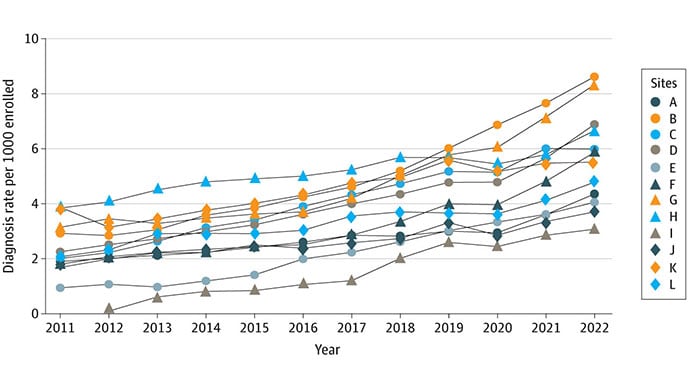

The issue I’m discussing this week is bound to be sensitive, so let me try to focus just on the facts. Yes, there are more diagnosed cases of autism now than there have been in the past.

The US Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, cites that fact and suggests that it implies the existence of an environmental cause of autism— as of yet unidentified — that, through careful research, can be identified, perhaps as early as September. The focus on an environmental explanation for the increase runs counter to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report suggesting that the increase is due to better and earlier identification. RFK Jr referred to that line of evidence as a “canard” — a useful excuse to protect entrenched interests that are actually the culprits. And although I think we know what entrenched interests he may be referring to, I’ll give him credit that his public statements keep an open mind about what environmental factors might be at play.

I thought, therefore, that it might be a good time to look at what we already know about environmental versus genetic triggers for autism to set expectations on what an HHS-sponsored investigation may be able to find. In other words, let’s look at the data. Autism: genes vs environment.

There’s a pretty interesting way to quantify how much of a disease may be due to things external to our genetic makeup vs inherent to that makeup: twin studies. And the cool thing is, these studies can tell us how much of a disease may be due to an environmental trigger even when we don’t know what that trigger might be.

To show you how this works, I’ll give two extreme examples.

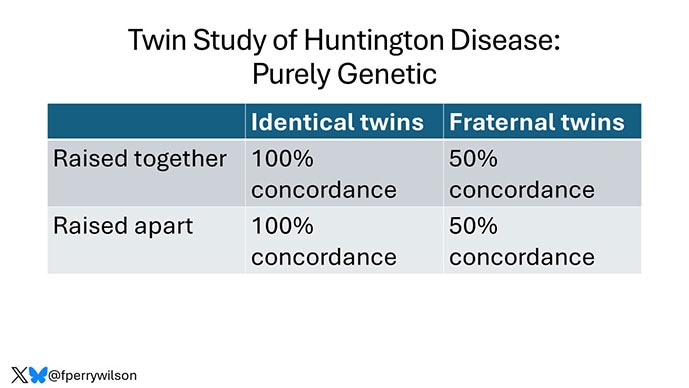

Let’s look at a condition that is basically purely genetic — Huntington disease — and examine how it should work among different types of twins.

Identical (monozygotic) twins share virtually 100% of their genetic code. Since Huntington disease is purely genetic, you’d expect perfect concordance among identical twins, regardless of whether they were raised in the same environment or not. There are actually a few case reports of identical twins raised apart — a rare occurrence — where both developed Huntington disease, as expected.

In contrast, fraternal (dizygotic) twins, share 50% of the same genetic information (just like nontwin siblings). As such, we’d expect some concordance between fraternal twins in terms of Huntington disease (since it’s a dominant gene, 50% of children of an affected parent are affected), but not perfect concordance. And, similarly, it shouldn’t matter whether these twins were raised in the same environment or not. I’m including the in utero environment here — basically, “environment” means anything not genetic.

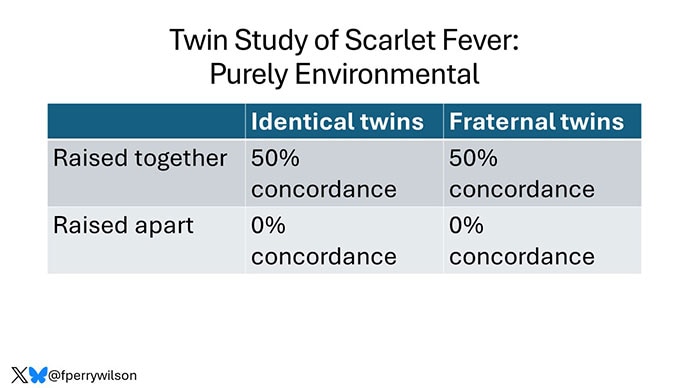

Almost no disease is purely environmental, because genetic variation might change the susceptibility to environmental toxins, but as an example of the other side, let’s take something like scarlet fever. This twin study examined concordance rates for scarlet fever between identical and fraternal twins and found them to be basically the same. In other words, susceptibility to scarlet fever is driven almost entirely by the environment kids are raised in, not by their genetic similarity.

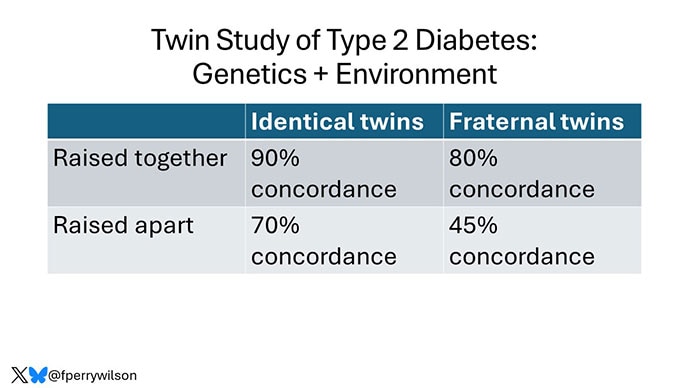

Then consider something like type 2 diabetes, which has both strong genetic and environmental components. Twin studies show a higher degree of concordance among identical twins than fraternal twins, but data from twins raised apart suggest a substantial environmental component. Studies vary, but most end up attributing about 60% of the risk to genetic and 40% to environmental exposures. And, to be clear, when I write “environment” here, I don’t mean toxins in the air or something — I mean the environment we have created, which is replete with calorie-dense, ultra-processed foods.

So, what about autism? If it is caused by some environmental exposure — a vaccine or vaccine ingredient, a pollutant, energy beams from space, whatever — we should see similar concordance between identical and fraternal twins, provided they were raised together. What do we actually see? Concordance rates among identical twins range from 60%-90% and, for fraternal twins, from about 3% to 30%. That’s a strong genetic signal.

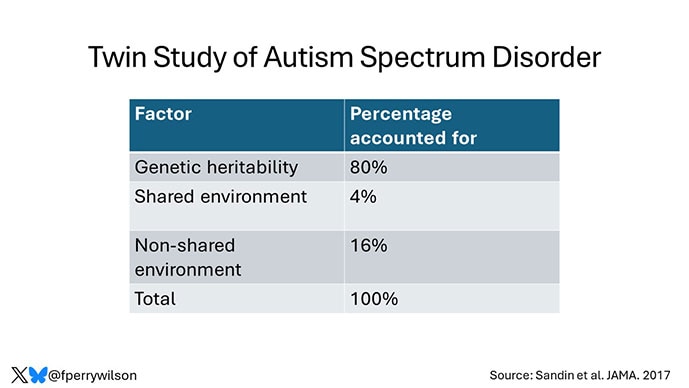

There are quite a few studies out there that dig in even deeper, but this one in JAMA is pretty solid since it comes from Sweden where, as I have mentioned multiple times before, healthcare is universal and so are electronic medical records. For what it’s worth, the estimates from this study are pretty similar to those from other studies.

Researchers examined about 40,000 twin pairs, as well as 2.5 million sibling pairs and about a million half-sibling pairs. The data suggested that 83% of autism diagnoses could be attributed to genetics, based on a high degree of concordance between identical twins vs fraternal twins. About 4% could be attributed to what are called “shared environmental factors” — these are things that siblings are both exposed to — for fraternal twins that includes everything from the womb on up until they leave the nest.

In that study, 16% of the diagnoses could be explained by non-shared environmental factors. This is interesting; it reflects a concordance in relatives after accounting for shared genetics even if they weren’t raised in the same environment. This could reflect some interesting epigenetic causes of autism or exposures (like certain illnesses) that aren’t highly shared between siblings.

I think there is something for everyone in these data. It’s fairly clear that the majority of cases of autism can be attributed to genetic factors, even if we don’t yet know entirely what those factors are. That does support the hypothesis that the observed increase in cases is due to more or better diagnosis — we just missed these kids in the past, or diagnosed them with something else.

But autism spectrum disorder is not Huntington disease. There clearly are environmental factors at play as well; not every pair of identical twins is concordant for autism, even if 90% are. And, even if there is concordance, the severity may differ between identical twins, indicating some gene-environment interactions.

So, is something in the environment the major factor leading to the observed increase in cases of autism spectrum disorder? Probably not, but it should not be ignored just because it isn’t the sole explanation. We should try to figure out what these other factors are.

Which means that now, the real work begins, because “environmental factors” is a big tent that includes essentially everything that isn’t genetic: mom and dad’s medical history, toxins and pollutants, infections, medications, and so on. Twin studies are not the way to figure out which of these is the culprit — more dedicated, cause-specific research is. I for one am happy to see some funding go in this area, but I will be quite surprised, and honestly skeptical, if we get an answer by September.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He posts at @fperrywilsonand his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.