In a study published May 28 in the journal npj Digital Medicine, University of Michigan researchers found that individuals with stronger seasonal sensitivity, which determines how a person’s body responds to changes in light, experience more lasting disruptions to their circadian rhythms. The study, titled “Seasonal timing and interindividual differences in shiftwork adaptation”, aimed to study how quickly people adjust their circadian rhythms, or internal body clocks, based on genetic polymorphisms, or variations in DNA among individuals. Several authors, including Ruby Kim, postdoctoral research fellow at Michigan Medicine, as well as Yu Fang, Michigan Neuroscience Institute statistician staff specialist, contributed to data collection and maintenance.

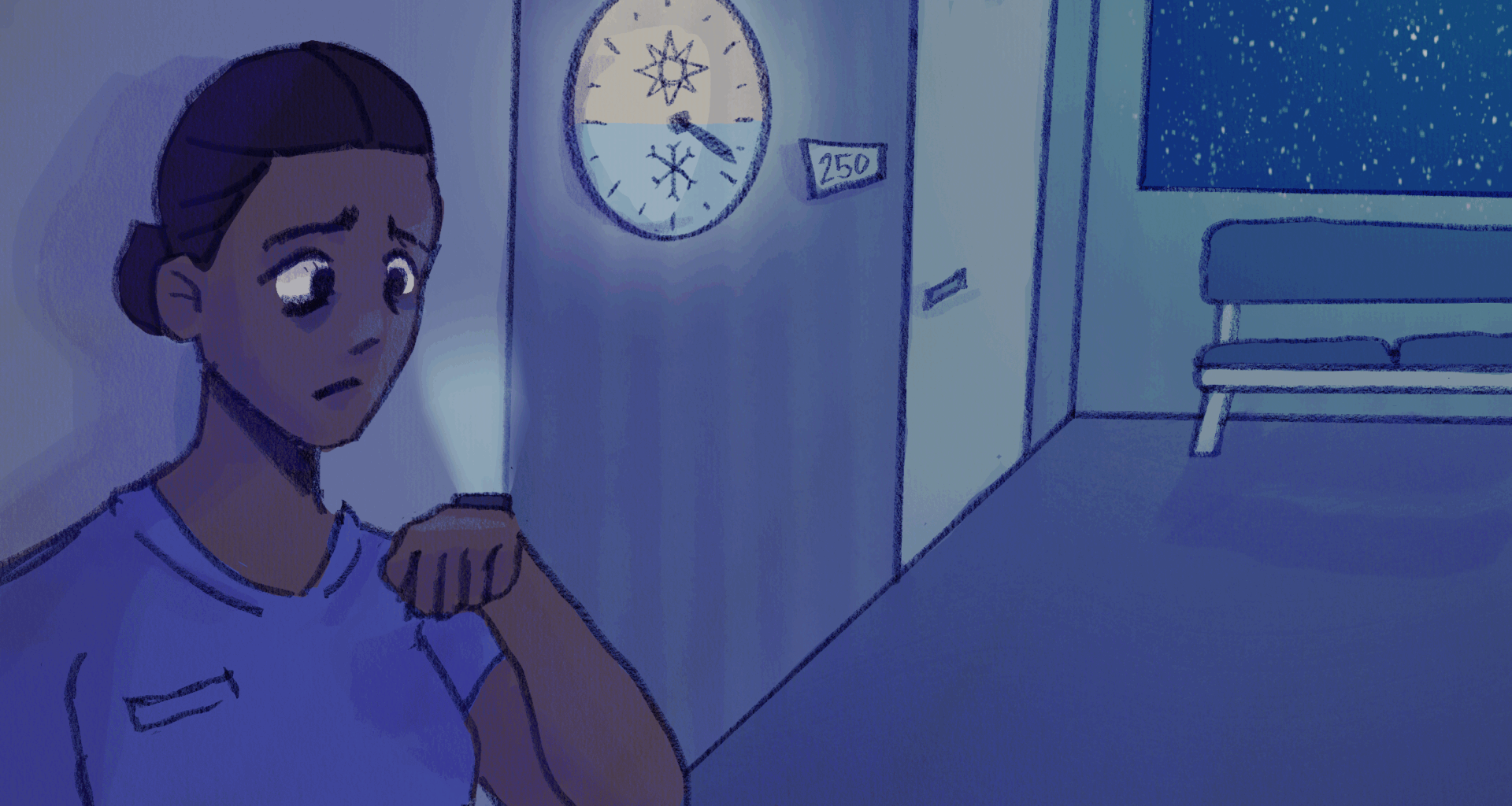

The University’s Intern Health Study evaluates stress and mood in 1500 to 3000 medical interns per year across the U.S. and China. U.S. participants provide step count, sleep and heart rate measurements via Fitbit fitness trackers. The 2025 study utilized data from the 2017, 2018 and 2019 cohorts of the Intern Health Study, during both day and night shifts. It found that while most interns quickly recovered from occasional night shifts, some individuals experienced greater circadian misalignments.

The study examines the dual oscillator model, which suggests the circadian rhythm consists of a morning oscillator that regulates morning activity and an evening oscillator for evening activity. Because nighttime lasts for a different amount of time depending on the season, this system may explain differences in circadian rhythm regulation across seasons. The study found that intern time spent awake varied by season, with longer periods spent awake in summer than in winter or spring. In an email to The Michigan Daily, Kim wrote the study provides evidence for the dual oscillator model being present in humans.

“The dual oscillator model tracking morning and evening is widely accepted in animals and evolutionarily conserved,” Kim wrote. “There’s lots of evidence of this mechanism in humans as well, but it’s often overlooked because we spend a lot of time indoors and with artificial lighting. Our study shows seasonal timing is still relevant and important.”

Because Fitbit devices can collect human activity data on a large scale, they are commonly used for mathematical modeling. Kim wrote this technique was beneficial to study the behavior of the 3,000 study participants without the need for lab simulation.

“The mathematical models enable us to extract information about real-world behavior, with thousands of participants going about their daily lives,” Kim wrote. “Shift work across such a large population would be difficult to reproduce in a lab.”

In an email to The Daily, Fang wrote managing large-scale wearable data was complex, as a collaborative effort was required to organize data that differed greatly by participant.

“Developing and maintaining a steady system collecting, storing, processing and analyzing large-scale data is a challenge,” Fang wrote. “Over time, we have put together an interdisciplinary team to ensure the quality, accuracy, integrity and security of the data. We follow established protocols to download, preprocess and quality-check the data needed for each project. We hope other UM groups who want to use large-scale wearables in their research can build on the infrastructure from our study.”

Kim wrote wearable devices offer accessible insights into biological timing using crucial signals such as one’s heart rate and sleep-wake cycle.

“There are multiple circadian rhythms throughout the body, including in heart rate and the sleep-wake cycle,” Kim wrote. “These two signals from the wearable data are useful because they could be measured quickly and noninvasively, and their relationship gives us some insight into internal circadian misalignment.”

In an interview with The Daily, Praneet Voleti, LSA rising senior and member of the University’s Biology Student Alliance, said a deeper understanding of circadian rhythms can improve knowledge of sleep-related disorders.

“Circadian rhythms are so related to sleep, and especially (in) recent studies, we see the importance of sleep and how it can improve our well being,” Voleti said. “It improves our focus the next day … So understanding more about circadian rhythms can allow us to advance our understanding about insomnia and other sleep-related disorders, and how we can better combat that.”

The study noted that misalignment between heart rate and sleep-wake cycle is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Voleti said similar studies on biological clocks could explore broader health outcomes.

“In terms of public health, it might be interesting to see the link between biological clocks and the spread of different diseases,” Voleti said. “If we maintain a proper schedule of our biological clocks, our bodies can be more healthy to combat different immune diseases. Especially with different epidemics, I think if we try to optimize our biological clocks, we can be more equipped to combat those epidemics and be healthier and be able to fight off those foreign bodies.”

Daily Staff Reporter Kayla Lugo can be reached at klugo@umich.edu.

Related articles