When David Richards was left with severe facial injuries after being knocked off his bike by a drunk driver, he faced a long road to recovery. The journey has now been made just a little easier by a pioneering NHS centre that prints replacement body parts.

Richards, 75, from Devon, was cycling in Meare, Somerset, with two friends in July 2021 when they were hit from behind. His friends suffered broken bones and he lost his nose and an eye.

“The driver was on his phone,” he said. “I was trapped underneath the vehicle and got severe burns down one side of my body and face.”

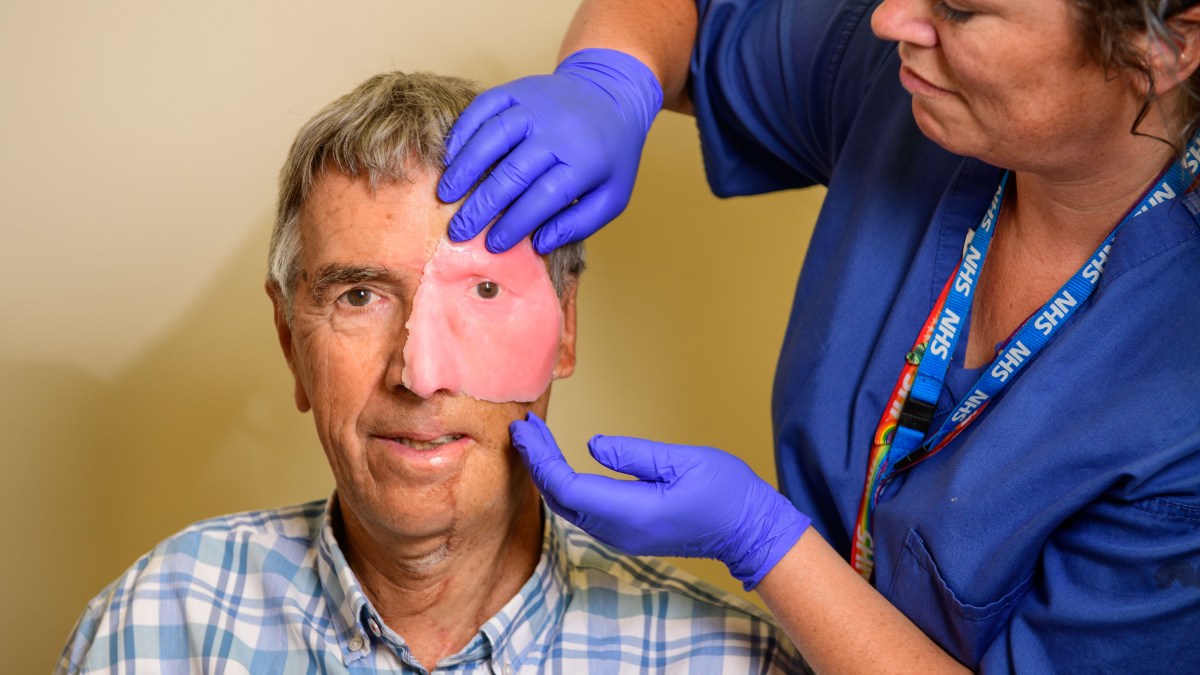

After a series of reconstruction operations he is one of the first patients at the Bristol 3D Medical Centre — the first in the NHS where 3D scanning, design and printing have been brought together on one site to produce bespoke medical devices and prostheses.

Amy Davey is the senior reconstructive scientist at the centre, which is part of the North Bristol NHS Trust. “We provide small facial and body prostheses — noses, ears, eyes, fingers, toes, even nipples,” she said.

“As a profession, we’ve long known that 3D printing would transform what we do. We’re a very small team — there are three of us, and we work very hard. And the motivation, really, is that there are so many people that we can help.”

For Richards, the process began with his face being photographed from several angles. The images were used to create a highly-accurate 3D digital replica of his head. This model was then used as the foundation to design a facial prosthesis.

In his case, a mould was 3D-printed and used to craft a prosthesis from silicone; for other patients, the parts of the prosthesis or a prosthetic implant could be printed from plastic or titanium.

Richards had previously experienced the traditional process, which involved making a plaster cast of his face and was time-consuming and messy.

“Now, they just take a few photographs from different angles, and the software meshes it all together. It’s incredible,” he said.

As well as being less intrusive, the new techniques can produce prostheses that are more accurate. “It’s those small margins that matter,” he added. “You look in the mirror and think, ‘Okay, I look a bit better today.’”

The prostheses are 3D printed to the exact measurements of the patient

ADRIAN SHERRATT FOR THE TIMES

Other patients at the centre include people who have had operations to remove cancers and babies with plagiocephaly and brachycephaly, conditions that affect the shape of their skull.

Previously, these infants would have needed a general anaesthetic to stop them from wriggling while a mould of their skull was produced to make a special helmet to help reshape their head. “With our 3D surface scanning, the baby can move around freely and happily, and a 3D-printed helmet subsequently produced from that scan,” Davey said.

By scanning patients while they move, her team can also make prostheses that deal better with the shifting contours of, for example, a face.

Her team is developing techniques and finding new applications for existing ones. 3D models, for instance, can be printed to help surgeons prepare for surgery. A model of a damaged kidney can, for instance, show not only the area to be removed but also highlight nerves and blood vessels to help plan the operation.

Most of the equipment within the centre is funded by donations to the Southmead Hospital Charity, the official charity of North Bristol NHS Trust.

What counts as a successful outcome, Davey explained, depends on the patient. For some, it could be a facial prosthesis that helps them feel comfortable enough to answer the door. For others, it might be a 3D-printed splint that helps shape scar tissue, or the use of 3D scans taken over time to monitor their healing.

“It’s not about making someone ‘complete’,” she said. “It’s about supporting their rehabilitation, whatever that looks like for them.”

Richards has been rebuilding his confidence since the incident

NORTH BRISTOL NHS TRUST

Richards is waiting for his latest prosthesis. A future version could be attached to his face using magnets, with metal studs embedded into the bone around his eye socket.

“You’d just put it on and it would click into place like a jigsaw piece,” he said. “But I want to try one [attached using an adhesive] first, to see if I’m happy with it before I go putting studs into my head.”

The real difference, though, may not be how it fits, but how it makes him feel. “Children can be quite blunt,” he said. “They’ll come up and say, ‘Mr, what’s happened to your face? Where’s your eye?’ That doesn’t bother me too much now, but maybe with a really good prosthesis, they wouldn’t notice.

“In the early days I would avoid crowds completely. I had to really push myself to be more sociable. I’d have to tell myself: ‘I’m going to go to my local yacht club and see how I get on,’ and I’d monitor my progress. Having a prosthesis that makes me look a bit better certainly helps my confidence and my ability to mix.

“The new prosthesis won’t solve all my issues. It won’t undo the accident. But it might just give me a bit more confidence. And sometimes, that’s what you need.”