In the corner of a stuffy courtroom in Stratford, east London, a distraught mother breaks down in tears as she tries to explain the behaviour of her teenage son — a “really good kid” who has never been in trouble before. Moments earlier, the 16-year-old boy pleaded guilty to having a 25cm-long Rambo knife stuffed down his trousers when stopped by police as he walked his girlfriend home one evening.

“I feel like I’ve failed,” his father despondently tells the court, after explaining the efforts he’d put into teaching his son about right and wrong.

It’s a scene heavy with sadness that is familiar to those working in youth justice: a rueful teenager, broken-hearted and exhausted parents, apologies and tears, punishment — but with the chance of redemption.

This teenager was caught with the knife in April this year as he walked through the streets of Newham, one of London’s worst boroughs for knife crime. The boy was standing just a few streets from Newham Hospital where stabbing victims are regularly treated. He spent a night in custody after his arrest, and three weeks later he made his first appearance at Stratford Youth Court to face the charge of possession of an offensive weapon in a public place.

When adults appear in the magistrates courts, cases are dealt with swiftly and appropriate punishment is reached. Sometimes the motives behind crimes emerge, but often they remain a mystery. In the youth courts, there is a greater emphasis on understanding why a teenager — especially one with no previous convictions — has ended up in trouble.

The teen with the Rambo knife has a particularly traumatic backstory, one which at least starts to explain the decision he made. His younger sister had fallen victim to an apparently random attack which left her older brother “traumatised” and believing he needed to carry a knife for protection.

Why carry the knife? ‘I wanted to scare them off, not use it — just to scare them’

Magistrate Aneeta Prem is the one tasked with exploring how he got to this precipice. “If you were confronted that day by a group of young guys, threatening you and your girlfriend, would you have used the knife?” she asks. “No,” says the teen. So why carry it? “I wanted to scare them off, not use it,” he says. “Just to scare them.”

Prem is an experienced magistrate who specialises in youth law, has an MBE for her pioneering work as founder of the Freedom charity, and in court she sometimes has to act like a headteacher admonishing an unruly pupil. She tells the young defendant that 262 people were killed with a knife in the past year. Her words are powerful and persuasive. But it is, no doubt, the same speech she has had to make many times.

“Looking at that knife, your mum is in tears,” she says. “The likelihood is if someone was threatening you, you would have taken the knife out and it may have been turned and used on you, which we see too often in this courtroom.

“If you carry a knife, that makes you the perpetrator. If you were an adult, we would be looking at you standing in the dock and sending you to prison.”

The teenager is told to apologise to his mother. Unlike adult courts, the parents are given space to address the room. “He’s a really good kid,” says his mother. “He has never been in trouble with the police before, so it’s a bit of a shock.”

His father, quietly furious, struggles to explain what has happened: “I’ve told him before the consequences of carrying a knife. He knows not to do it. I don’t understand where this is coming from.” When the words desert him, he looks down and says: “I feel like I’ve failed.”

The teenager is given an eight-month referral order as punishment, and Prem tells the boy on his way out: “It’s heartbreaking that your dad is blaming himself. You need to find a way of making it up to your parents.”

Bus killers already had knife crime convictions

It was January 7 this year when two teenage boys armed with machetes boarded the 472 bus in Woolwich Church Street. It was an ambush that had been carefully planned; they quickly rushed to the upper deck and brutally attacked 14-year-old Kelyan Bokassa, stabbing him 27 times.

In a matter of moments, they ended the life of Kelyan as he made his way home from school. And they shattered the lives of countless others, including their own.

Kelyan Bokassa was stabbed and killed as he made his way home from school

PA Media

In July, an Old Bailey judge will decide how many years the teens must serve of a life sentence before they get the chance of freedom, and full details of the horrific crime will be revealed. But it is already known that both boys had received referral orders in incidents before they turned into killers — one for mobile phone robbery, the other for possession of a knife.

Referral orders are commonly deployed by magistrates in the youth courts, to try to guide children away from crime while stopping short of sending them into custody. Convicted youths are told to sign a contract which will last between three and 12 months, in which they agree to attend learning and rehabilitation sessions with volunteers and a youth offending team worker.

Government statistics show that just over a quarter of juvenile defendants who are punished with a referral order go on to re-offend — down by nearly 10 per cent compared to a decade earlier.

A former chair of the Youth Justice Board once called referral orders “the jewel in the crown of youth justice”, and the data shows they are more effective than other forms of punishment, such as fines and “detention and training orders” — essentially youth prison. But there are times when they do not work, with utterly tragic consequences.

One of Kelyan’s killers was sentenced for his involvement in a knifepoint robbery in February last year, when a teenager was threatened with a machete in east London’s Jubilee Park and ordered to hand over his mobile phone.

He was still serving his referral order at the time of Kelyan’s murder, and court records show he had breached the terms of the order several times, leading to a stern telling off from a magistrate, but nothing further. Sadly, these interventions did not work. But for some teenagers, sessions with youth workers can prove to be a vital turning point.

Knives carried for ‘protection’

In March, the Standard observed as three magistrates sitting in Highbury spent the morning dealing with the latest crop of teenage Londoners to run into trouble. Fifteen defendants to deal with over three hours, some to be sentenced, some adjourned for their trial, and others put off until another date for procedural reasons. The cases included mobile phone robberies, the theft of a £900 coat, car-jacking, assaults on police officers and possession of weapons.

To a 17-year-old boy, the lead magistrate spelled out just how referral orders work after the teen admitted carrying a knife in the street outside Westminster College in October last year. “You are going to end up with a criminal conviction which is unfortunate,” he said. “But you have got some help from the youth offending services, and the referral order gives you a way in to the services they can provide.

“You are going back to live with your mum — turn your life around, get the help you need, and hopefully we will never see you again. You will go to the referral panel with mum or dad, come up with a contract you have to agree to, and decide what are all the things you have to do.”

The magistrate added a final warning: “Do everything they ask you to do, and at the end of that six months it will all be done. If you don’t keep to the terms of the contract, you have to come back here again.” The court heard how the teenager’s problems stemmed from seeing a friend being fatally stabbed in front of him. He started smoking cannabis, and took the decision to carry a knife for “protection”. He “wouldn’t have used it to injure anyone, but would have taken it out to brandish”, the teenager insisted.

In youth courts, the defendants are always accompanied by at least one adult — parents, extended family, carers, or support workers — to help them through the legal process and offer extra information to the magistrates.

This boy was accompanied by his father, who has been encouraging his son to join him at work in order to find a potential professional career path. “We know he has witnessed something really horrific,” the father said of the trauma his son went through. “I’m pretty sure that’s affected him. We are just hoping things will improve from here onwards.”

The teen told the court his friend was murdered at a time when “everyone was getting stabbed left, right and centre”.

The magistrate expressed the hope he can get counselling through the referral order, and sent him away with a familiar warning. “Carrying knives puts you in loads of danger. People think they are doing the right thing, but they are putting themselves at more risk.

“When you look at cases, people say they are not going to use it but they end up in really dangerous situations. People are getting hurt and people are getting killed.”

Magistrates adopt different personas to try to best deliver the anti-knife message, but it is without doubt the horror and tragedy of real-world examples that show just how perilous it can be to carry a knife on London’s streets. In February 2022, Muhamoud Mohamed Mahdi confronted two teenagers in Burnt Oak, north-west London, over a petty turf dispute, and then went to fetch a knife that he had stashed in a nearby alleyway. But he was disarmed in the ensuing fight, before one of the teenagers, Christian Kuta-Dankwa, picked up the knife, chased Mahdi and stabbed him to death. Kuta-Dankwa, then 19, is now serving a life sentence for the killing.

.jpg)

Muhamoud Mohamed Mahdi was chased and stabbed to death after confronting two teenagers in Burnt Oak

Met Police

The Labour government has promised to reduce knife crime by 50 per cent within the next decade. But the sad reality is that, right now, if a teenager falls victim to a homicide in the UK, it’s overwhelmingly likely — 83 per cent — that they have been stabbed.

Lawyers and magistrates in youth courts spend much time attempting to convince teenagers caught with knives that the dangers are real, before they either end up locked up or dead.

Highbury Corner youth court handles cases involving defendants as young as 10, up to 17-year-olds, from across north London, sitting several times a week and usually with days packed with cases waiting to be heard.

Along the snaking corridor leading to the dedicated youth courtroom there is metal seating bolted to the ground, broken up into collections of two and three chairs, probably to discourage large groups of defendants gathering together.

Typically, teenage boys sit looking glum alongside a despondent parent, hoping to be called in when court starts at 10am but knowing it could be hours before their turn comes. Inside the courtroom, defence solicitors whose cases are ready to go swarm around the list caller — the court official in charge of the day’s schedule — asking for an early slot.

Informal conversations break out across court before the session begins — Youth Offending Team workers discuss who might care for an accused teen if he’s granted bail, whether rehabilitation has been lined up, and how a boy who failed to meet the expectations of a referral order could be dealt with next.

Prosecution and defence lawyers also tussle over criminal cases to see whether they could be dropped, in exchange for an out-of-court disposal like a caution. “I want this dropped. I’m not happy,” complains a persistent lawyer, representing a boy who is believed to have been groomed into gang activity before he was caught with a knife. “He’s missing school, the parents are missing work.” Her petition ultimately fails, as the case was adjourned for more checks to be made.

Highbury Corner youth court handles cases involving defendants as young as 10, up to 17-year-olds

PA Archive

At Highbury, the courtroom is more spacious than the cramped surroundings in Stratford, but both have a similar layout — magistrates on a raised platform at the front, facing rows of plain wooden desks in a set-up similar to that of a typical school classroom.

Some of the young defendants appear in the secure dock on the right-hand side of the courtroom, listening to proceedings behind thick Perspex screens with custody officers for company. But most of the accused troop into court alongside their parents or carers and sit at the desks next to their solicitor.

Youth offending team workers are on hand to offer practical assistance on possible punishments, court officials work hard to ensure that hearings are called on back-to-back, and there is always a prosecutor stationed on the front row of the legal desks, to present the case against each young person.

Court officials and lawyers are careful to refer to the defendants by their first names, sparing them the dehumanising surname-only treatment of the adult courts. In the youth courts, defendants play an active role in hearings rather than being effectively sidelined as their lawyers do all the talking. The accused teenagers are cajoled into speaking, apologising, explaining why they did what they did, and the magistrates attempt to ensure that some of their words have sunk in.

The courts are brimming with lawyers and professionals who spend large parts of their lives on the frontline of youth justice, and everyone involved knows this is a tough environment to work in. They exist in under-funded institutions, battle bureaucracy on a daily basis, and have to tread a fine line between protecting the youths so they can be rehabilitated and punishment for those bringing crime to London’s streets.

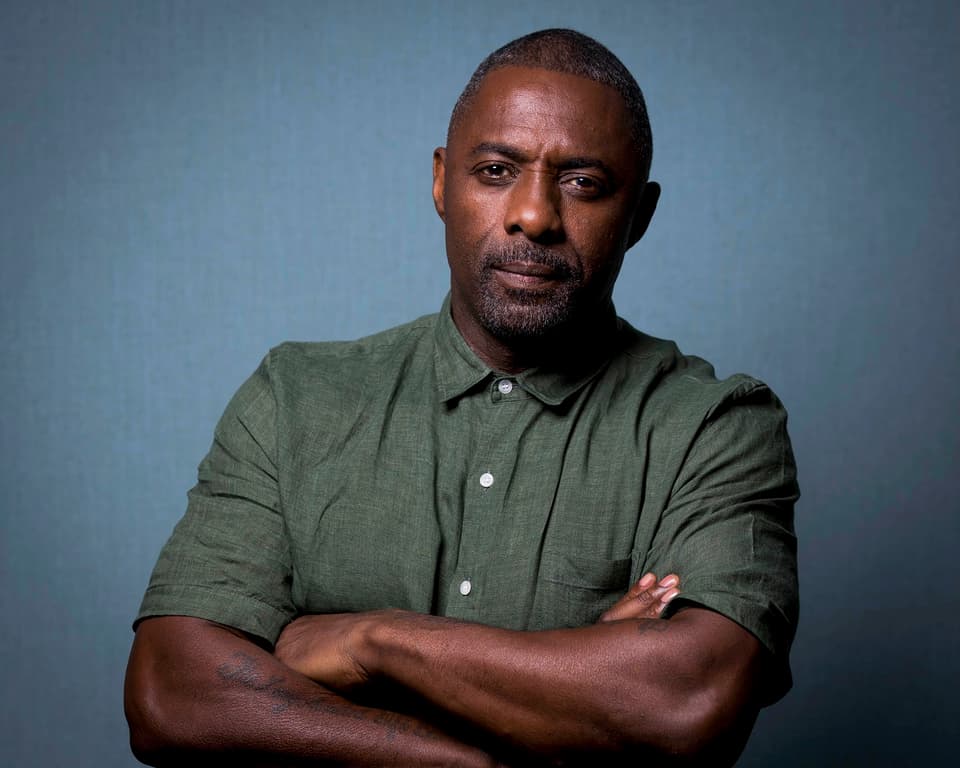

Actor and knife crime campaigner Idris Elba

Scott Garfitt/Invision/AP

In March this year, police raided the east London home of a 17-year-old boy and seized two machetes, after being called out by the teen’s grandmother. He already had a conviction, from 2023, for carrying a flick knife outside Westfield Stratford, so a spell in custody for a second offence appeared to be likely. But at court the two charges — of possessing offensive weapons in a private place — were dropped after prosecutors had to concede the machetes were not specifically banned weapons under the existing law when held inside a person’s own home.

In the Government’s Crime and Policing Bill, it plans to toughen sentences for some knife possession offences and strengthen police powers to seize weapons, even when they are held in private homes.

White, middle-class areas are also affected, perpetrators are getting younger, fear is spreading

Idris Elba

Actor Idris Elba is campaigning for an outright ban on the sale of machetes and zombie knives through his Don’t Stop Your Future initiative, and has built a coalition of support including from The Ben Kinsella Trust, Sir Keir Starmer and King Charles.

“So many people dismiss knife crime as something that doesn’t affect them, assuming it’s a black and brown, urban and gang-related problem — but this couldn’t be further from the truth,” he said.

“White, middle-class and rural areas are also affected, perpetrators are getting younger, and fear is spreading.” Elba has urged politicians to look beyond the courts and police stop-and-search to find the root causes of young people carrying knives.

Actor Idris Elba has called for a move to round-ended blades in his anti-knife crime campaigning

PA Archive

The Government has already pledged to expand the Young Futures programme, with a network of support hubs around the country — staffed by youth workers, mental health support workers and careers advisers — aiming to help young people access support services and divert them into positive activities.

For the past six years, the number of knife or offensive weapon offences committed by children has steadily decreased, but the rate of cases going through the criminal justice system is still 20 per cent higher than a decade ago. The Youth Justice Board of England and Wales called the figures “worrying”, and its chair Keith Fraser said reducing knife crime involves a deep understanding of the context in which it occurs.

“There is very weak evidence to support that ‘scared straight’ initiatives, weapons amnesties, increased stop-and-search or mandatory sentencing have any sustained impact on knife crime,” he said. “Initiatives that do work are social skills training, mentoring and tailored support with education, housing and employment.”

Owen Cooper as Jamie Miller and Stephen Graham as Eddie Miller in Adolescence

Courtesy of Netflix

In January, the award-winning Netflix drama series Adolescence successfully tackled important issues like knife crime, teenage violence, social media menaces and misogyny, bringing them to the top of the political agenda. Starmer reacted by suggesting the four-part show should be essential viewing in all UK schools.

The drama drew viewers into the immediate aftermath of a stabbing; the police station, searches, interviews and the anguish of the killer’s parents. Although we did not see the court case itself, we as viewers saw actress Erin Doherty giving a mesmerising performance as a clinical psychologist assessing the boy in custody, producing a report which would play a vital role in the justice process. And finally, we learned — through the devastated eyes of the boy’s father, played by Stephen Graham — that his son would be pleading guilty to murder.

The drama “lit a touch paper” under debate around the issues it featured, said the PM. “What happens in the drama could really happen anywhere, and almost happen to any child.”

The killer in Adolescence, just like Kelyan’s murderers, would have ended up being sentenced at a Crown Court due to the gravity of the offence. The teenage criminality that the public usually gets to see is of the most serious kind, rather than the work of the youth court that deals with less serious offences.

Erin Doherty giving a mesmerising performance in Adolescence as a clinical psychologist assessing a boy in custody

Courtesy of Ben Blackall/Netflix

Youth courts are designed to protect the defendants from the public glare that can come with being dragged through adult courts. Their identities cannot be revealed, and members of the public are explicitly banned from hearings unless they are accompanying a child defendant or appearing in a professional role. While journalists are allowed into hearings, reporting restrictions are in place for good reasons and what can be published is limited.

‘I’m sick of coming to this court’

It’s now well-known that delays in the justice system are endemic, and the youth courts are not immune from that problem. The average time from an offence to the end of the court process is 225 days, the longest timeframe on record.

At Highbury, a teenager arrived hoping to be sentenced for taking a claw-shaped knife to Kilburn High Road. It was just the kind of incident that scares Londoners — an armed youth threatening to attack the public, who was willing to resort to actual violence when arrested by police.

He pleaded guilty in October last year and turned 18 in the months he waited to be sentenced, and now there was a problem as youth offending and adult probation services had not done the necessary collaboration on reports for his sentencing hearing. The teenager flew into a rage at the news of a further delay, the like of which are commonplace in Britain’s ailing criminal justice system.

“Why, why, why, every week, adjournment,” he shouted, throwing down the crutch he was using. “I’m sick of seeing these people, I’m sick of coming to this court.”

Amid the chaos, a probation worker suggested there were concerns about gang links which needed further investigation, and the magistrate conceded another adjournment. But the teenager was adamant he wanted to be sentenced that day, not grasping that the reports were aimed at finding a way — possibly by rehabilitation, a curfew, electronic tag — to keep him out of prison.

“I’m not coming back to this court,” he yelled, while his lawyer chipped in that he has mental health struggles. “It’s stressing myself out. I want to be sentenced today and gone.”

Ultimately he was ejected from the courtroom by security guards, and then after a scuffle in the corridor he was ordered out of the courthouse entirely. It was an unpleasant display of the possible impacts from delays in the justice system.

‘Don’t mess up your life’

London is plagued by the scourge of knifepoint muggings, and a third of all robberies carried out by culprits aged under 18 happen in the capital. Over at Stratford, four teenage boys stood together in court to all plead guilty to a mobile phone robbery where the young victim had been forced to hand over his possessions or be stabbed.

Magistrate Prem agreed to grant them bail ahead of a sentencing hearing when detention and training orders — a period of youth imprisonment combined with supervised training and supervision sessions in the community — is possible.

All four boys, aged 16 and 17, are banned from associating with each other under the terms of their bail, but two failed the test immediately while still in the courtroom. “Stop talking,” the magistrate scolded. “You are not allowed to do that.”

But sometimes the words simply do not sink in. Two of the teenagers left the hearing deep in conversation, soon joined by a third, discussing their afternoon plans. Their lawyers attempted to ram home the consequences of the court orders, but sometimes it is a battle that cannot be won.

Young suspects being arrested in south London for alleged possession of dangerous weapons

Getty Images

Labour’s stated aim to halve knife crime in a decade will be judged by the statistics in years to come. The effectiveness of the courts can be assessed by rising or falling re-offending rates. But only the actual details of the crimes, gleaned from court hearings themselves, offer up the reality of London’s knife crime problem, going deeper than simplistic headlines about bad teenagers in a lawless society.

Age of violent crime suspects getting lower

According to a new report using figures from the Met Police, child violent crime suspects are getting younger, as an increasing proportion of children aged between 10 and 14 years old are suspected of committing violent crime in London, in comparison to other young people

A 14-year-old boy was stopped by police at Euston station on his way home one evening in February, and in his pocket was a five-inch dagger. He spent the night in police cells before being taken to court in Highbury, as his mother desperately arranged emergency care for her other children so that she could be at the hearing.

He stood alongside his strung-out mother and, softly-spoken, pleaded guilty to possessing a weapon in public, gaining a criminal conviction that will hang over his adult life.

The boy went missing from home a few months earlier, and there are concerns he was being exploited by a gang. But he told the court he’s keen to get back on track, and is enjoying the routine of school studies again. “It gives me something to do during the day,” he said.

The teenager said he was told to carry the knife after travelling to Watford to watch a friend make a music video.

“After the music video, one of the other boys called me over. He said, ‘Take this’. I said no, I’m not going to do this.” But ultimately he succumbed to peer pressure, he said.

The teen was sentenced to a six-month referral order, and sent away with a warning from the magistrate that a second knife offence will mean an automatic six-month spell in custody and many more “uncomfortable” nights in the cells.

“Don’t mess up your life,” he added. “We don’t want to see you through that door again, unless you come back as a lawyer or a magistrate.”