Did the title, The Emperor of Gladness, lead the story or did it unlock while you were writing these characters?

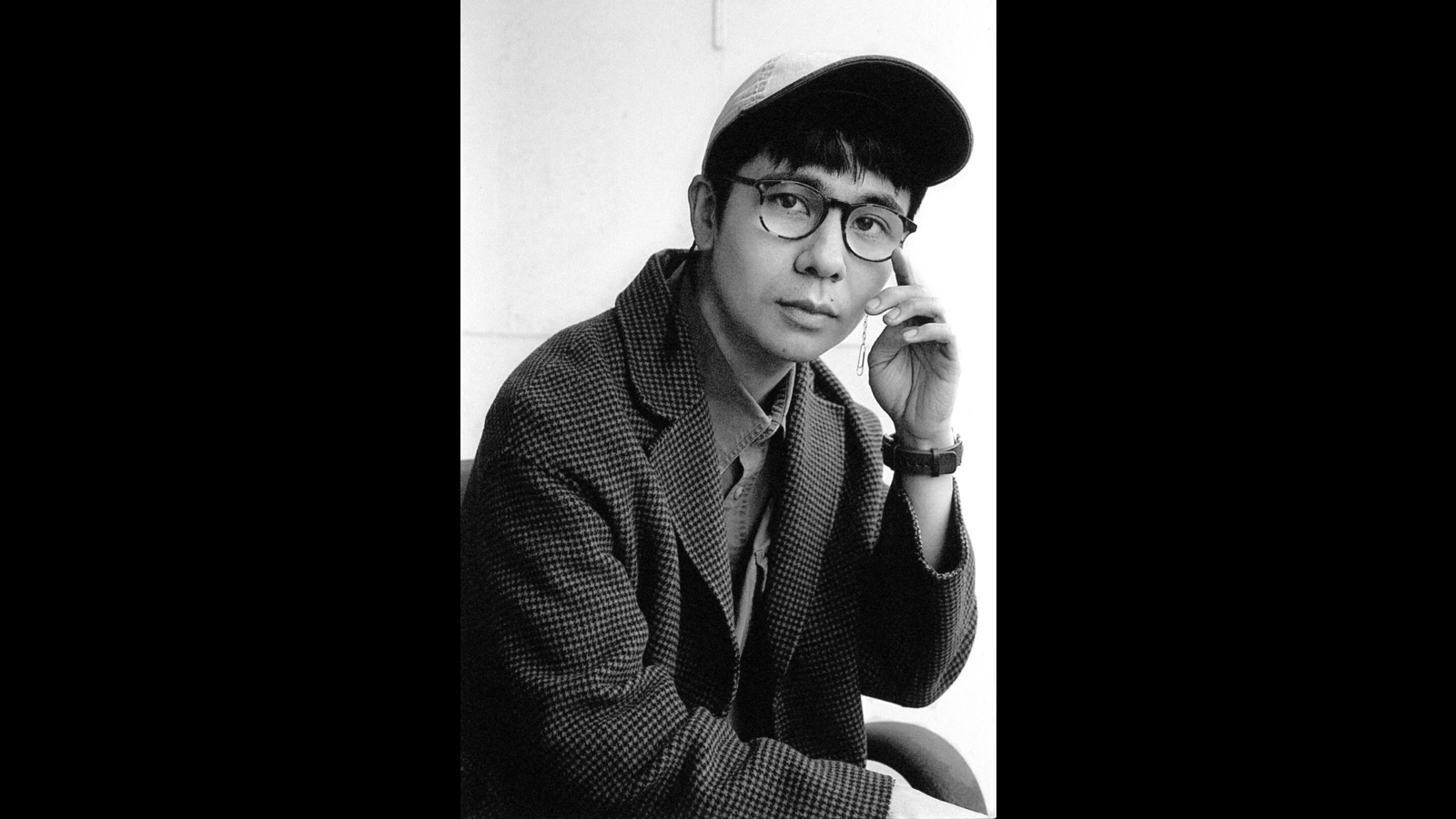

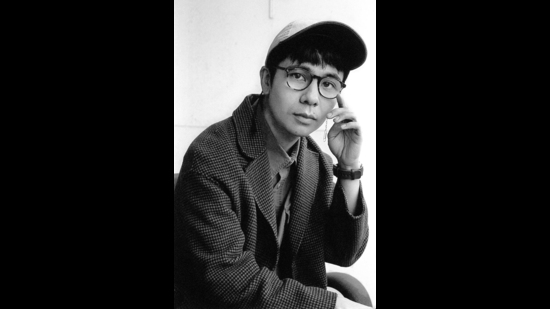

Author Ocean Vuong (Gioncarlo Valentine/Courtesy https://www.oceanvuong.com/)

Author Ocean Vuong (Gioncarlo Valentine/Courtesy https://www.oceanvuong.com/)

It haunted the story. It comes from Hamlet. “Your worm is your only emperor… We fat all creatures else to fat us and we fat ourselves for maggots.” No one gets to heaven without going through the maggot. And for me, that was a big treatise about how I think about work and life. And also, Wallace Stevens – “the only emperor is the emperor of ice cream”. That poem is about a funeral. I love these paradoxes. The title feels very triumphant, regal. But as you read, you realise that the book is trying to redefine what an emperor is. An Emperor Hog is named after who will eat it. It doesn’t rule anything. And Gladness is a town that doesn’t exist. And so, to be The Emperor of Gladness is to be the emperor of nothing.

You’ve said before that the sound and rhythm of words, at times, matter even more than the story itself. How do you let sound guide you when you write prose?

Gosh, I don’t really know. When I grew up, I learned about sonnets and the iambic pentameter. And I really resisted that rhythm. Da da da da da. I was like, there’s got to be another way to gallop, to dance. English poets have used this rhythm for hundreds of years. But to me, it’s just too stagnant. Maybe it’s informed by Vietnamese, maybe an internal rhythm, but I try to look for a different echo when I’m writing. A sentence is almost like a musical score and it’s always different for every work.

When you first published On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, it instantly became a phenomenon. Did that success affect the way you approached the second book?

Well, it’ll be disingenuous to say absolutely not. Although it’s not conscious to me. Being a Buddhist, I’ve learned that ‘you make something and it’s not you’. And so, I don’t really have a close relationship to ideas of fame, or notoriety, or success. I acknowledge it. I know it’s there. But I was very surprised that [On Earth] did so well.

Little Dog from On Earth and Hai from The Emperor of Gladness feel like they’re versions of each other. You’ve even described The Emperor of Gladness as a reincarnation of On Earth. What made you want to give that same voice a new body and a new life?

Thank you for saying that. On one hand, it’s modelled after the spiritual idea of reincarnation. But on the other hand, we are often asked as authors, musicians and artists to reinvent, rebrand ourselves, do something new. Even in the grocery aisles – “now better tasting!”, “now with a brand new look!” – there’s always this anxiety of newness. And I never felt that to be true with the questions I was asking: colonialism, violence, memory, family, migration, queerness, loneliness. How can any one book extinguish all these questions? Our questions could be a lifetime’s work and they still might not be done. I wanted to show that I can go back and that the ideas are not exhaustive. And again, in a world that values progress and growth, to deliberately stay in one place is kind of an ultimate taboo.

I was especially moved by the way you tackled the long-term effects of war, not just on those who are in the thick of it, but also across generations. How has war shaped your world view and writing?

I think war is the most common and steadfast reality of our species. If you think of the first works, I mean, The Mahabharata is about war. Gilgamesh, The Iliad, The Odyssey – all about wars. In the publishing world, which is largely made up of people from the upper middle class, most of life in literary fiction is about living in suburbia, having relationships and affairs! But you realise that that’s an exotic, rare thing; that most of our human life is about geopolitical violence and war. Most of what is considered as highbrow literature is about static, safe, suburban or city life. And then when you read fantasy, it’s all about war. I think it’s interesting that those books are more honest to our human condition, even though they’re about non-reality. So, to me, it was really important to centre how war haunts so much of our life, history and our material production, including novels.

The story pays attention to people who are forgotten, especially those who lose themselves to addiction. What drew you to focus on this part of American life?

Well, this is the most common part of American life and I just didn’t see it [reflected in literature]. When I did see it, most of it felt like “poverty porn”. These subjects and communities are used as symbolic pawns by someone outside of that community, who benefits monetarily from their lives, and then this material will be read by someone outside of that community too. If you drive through USA, you’ll realise that very, very few places look like New York City or the Hamptons. Most places are down-and-out trailer parks, broken down infrastructure, and dirt roads. I don’t believe that my work is corrective but it’s just adding something new and expanding what the novel can perform.

One of my favourite lines in the book is, “being okay is better than being happy.” Where does this philosophy come from, and how does it shape your writing?

Well, I think it’s a response to the fetishization of happiness. There’s a really painful thing that parents say to their children, “I just want you to be happy.” It seems very innocuous, but I was like, do you know how hard it is to be happy? There’s no procedure or a map for it. Happiness is often so random and subjective. And in this culture, it’s been captured by commerce. You want to be happy? Take this pill, get this car, go on another retreat. The goalpost of happiness keeps being moved, so that we can keep funneling money into the system. So, I thought, what would happen if we reframe the obsession with happiness with a goal for contentment, fulfilment, “okayness”? Also “okayness” being dull is such a Western/American privilege! Because there are people in the world right now who would give everything to be “okay”.

This novel is based on your time caring for someone with dementia, and that person takes the form of Grazina in the book. How did that period of your life contribute to your understanding of memory, of presence? And did it in any way influence the way you approach storytelling?

Gosh, no one has ever asked me that, that’s a really wonderful question. I think it influenced me more than I know. I was 19, maybe 20, and [Grazina] was 84. And when you go through that as a young person, you put your blinders on and go through the day. I think the main thing I learned was that there is no true reality. There’s just a reality that the majority of people confirm, and then there’s the reality a small minority confirms. And people with dementia or mental illnesses make up this minority. They see something the majority of people don’t see. You know, a fly has compound eyes, it sees hundreds of images. And we see one image. So, it bodes the question – Whose truth is true? But both are real. I think it taught me that, in fiction, all points of view are valid; that there is no ultimate, central truth to what I’m doing. That helped me write different characters.

The book is surprisingly funny. There’s an abundance of sharp jokes and there are tender moments of laughter as well. Was that range of humour always a part of the story, or was it a conscious choice?

Well, humour is a part of my life. My friends always say, “You’re so silly, but your books are so sad.” In the first book, I really did not want to be funny. I had jokes, but I didn’t put them in because I wasn’t writing about my history. I was writing about my elders’ history and I had to handle that with care and reverence. I knew that most of my readers would be non-Vietnamese people, and I did not want to invite non-Vietnamese people to laugh at my elders. The line between laughing with you and laughing at you is very, very thin. And I didn’t want to forsake the material and betray my elders’ by making [the book] into a joke.

You wrote the first draft for this book by hand. Does writing by hand affect the way you write?

Writing by hand is more exploratory. When you write by hand, something happens in the middle of the sentence. You realise, “Oh, this is not what the sentence is about. It’s about something underneath.” And then you start to dig underneath the sentence. If that happens on every sentence, or every other sentence throughout the span of the novel, the novel suddenly starts to rise up. Writing by hand allows you deep, deep depth.

If you were to make an “Ocean-Vuong Reading List”, what books would be on it?

There’s so many. I mean, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. There’s a really great book by Agota Kristof called The Notebook. It’s a trilogy. She was a Hungarian refugee in World War II who then learned a very rudimentary French and then wrote in that rudimentary French. The sentences are so simple and short, but it’s so, so beautiful. Ways of Seeing by John Berger. Clarice Lispector is another one. The Hour of The Star is really beautiful. That’s just prose. In poetry – Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Bhanu Kapil’s Humanimal is really, really beautiful.

I read that you have plans to publish just one more piece of work. You spoke about the double-edged sword of finding success, and how authors afterwards just publish whatever. As a fan, I have to ask, surely this is a case of never say never! I hope to get more than one more piece of work from you.

I said that somewhere, yes. But I said one more collection of poems. In total, I hope to write eight works, modeled after the Eightfold Path. So, I’m halfway there. So much of our world, particularly as a successful author, is about endless production. And I also discovered that there’s a double standard for meritocracy. When I was a struggling poet, a lot of magazines, journals, publishers were saying, “Oh, you need to be better. This is a meritocracy. But now that I make everybody money, they want anything – they want a grocery list. That’s not meritocracy, that’s capitalism! So, I think it’s important for me to find a way to stop.

Rutvik Bhandari is an independent writer. He lives in Pune. He is a reader and a content creator. You can find him talking about books on Instagram and YouTube (@themindlessmess).