Supermarkets will be forced to incentivise customers to swap certain foods for healthier versions – but experts say it’s unclear if the plan will work

One day soon, when you are browsing the supermarket shelves, you may find yourself being “nudged” into buying something you didn’t intend to – something that’s better for you.

Large food stores will be given targets for making the average shopping basket that little bit healthier under the Government’s new plan for tackling the UK’s obesity crisis.

The goal is that people end up consuming slightly fewer daily calories, which, over time, would have a cumulative effect on weight, the Department of Health and Social Care said. “Cutting the calorie count of a daily diet by just 50 calories would lift 340,000 children and 2 million adults out of obesity.”

Officials have said the policy could mean people consume 80 calories fewer per day if fully implemented.

The UK certainly has a growing weight problem, in common with most other countries. But experts are divided on whether this approach will work.

Food swaps are more complicated than you think

Stores will be told to incentivise consumers to make ‘healthy swaps’, using tactics like reducing the price of healthier food, while avoiding price promotions on fattening options like biscuits, cakes and crisps.

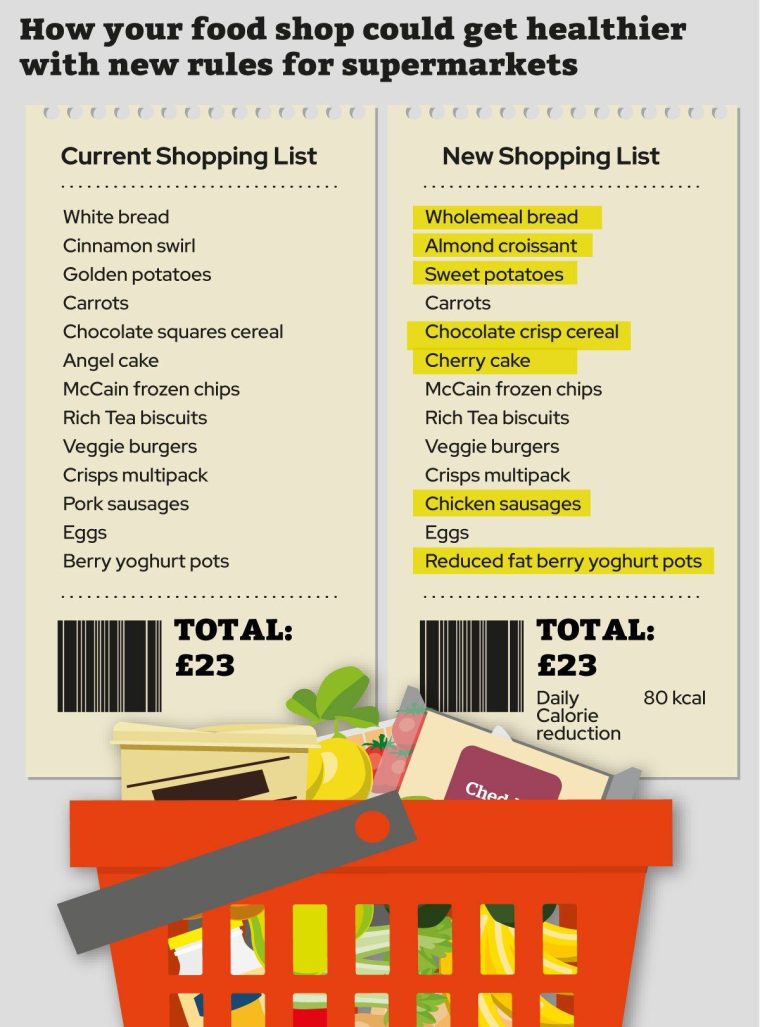

The Government has not yet given the details of which foods it wants promoted or discouraged. But Nesta, a UK health charity that is advising the Government, has given examples of the kind of swaps that would slightly cut our daily calories.

Example shopping lists taken from Nesta’s report

Example shopping lists taken from Nesta’s report

Some of its recommendations seem uncontroversial, like replacing pork sausages with chicken ones, as they are lower in fat.

But it is not always easy to define what makes a food healthy or unhealthy and there can be genuine debate about this among scientists.

For instance, according to Nesta, people should be nudged into buying low-fat yogurt. But the NHS Healthier Families site urges people to get low-sugar yogurts.

Low-fat yogurts are often higher in sugar while low-sugar yogurts can be high in fat – yogurt that is low in both sugar and fat often isn’t that tasty.

The different views on yogurt may seem a small matter, but it reflects a broader disagreement between food scientists about whether fat or sugar is the chief dietary evil.

Nesta also wants people to swap fizzy drinks for the diet versions, but some scientists – including the Government’s own advisory committee – say there is conflicting evidence on whether artificial sweeteners are safe. And the committee said young children shouldn’t have diet drinks.

Another swap Nesta recommends is buying wholemeal bread instead of white bread. Wholemeal bread has more fibre, which tends to reduce constipation, but the two products often have the same calories, gram for gram.

The Government will need to work out if its priority is calorie cutting or improving health more broadly, which is even more ambitious – and difficult to achieve.

The real impact of cutting 50 calories a day

A bigger question is whether someone who is nudged into making the lower-calorie swaps really would lose weight. The Government mentions cutting 50 calories a day while Nesta has also calculated that if people could be nudged into consuming 80 fewer calories a day, the rate of obesity would reduce by nearly a quarter.

Evidence from trials suggests they would not, because people’s bodies tend to adjust in response to a small calorie deficit to maintain a steady weight, said Professor Tom Sanders, a nutrition expert at King’s College London.

For instance, their metabolism may slow, they may expend less energy, or they could eat slightly more at their next meal. “In practice, individuals adapt to small reductions or increases in calorie intake,” said Professor Sanders.

People need to make an effort to be eating at least 300 calories a day fewer for it to affect their weight, he added.

Another problem is that if unhealthy foods like biscuits and cakes become more expensive at supermarkets, people could simply buy them from smaller shops. “A lot of less healthy food and drink is purchased from local convenience shops and takeaways,” said Sarah Woolnough, chief executive of health think-tank The King’s Fund, although she added that she welcomed the plan’s ambition.

If supermarket nudging won’t work, what else could the Government do? According to Woolnough, we need bolder measures, including cutting the number of fast food shops, clamping down on junk food advertising, and funding more weight-loss clinics.

Sanders wants wider-scale societal changes so we drive less and get more physically active.

Unfortunately, no Western country in the world has so far managed to reverse its obesity epidemic. Whatever the solution is, no one has found it yet.