KUALA LUMPUR, July 2 — The Ministry of Health’s (MOH) drug procurement decisions of late have sucked pharmaceutical multinational corporations (MNCs) and local generics manufacturers into a maelstrom of issues.

Speaking to CodeBlue on condition of anonymity to relate sensitive discussions, eight sources, mostly from industry, highlighted multiple procurement problems at the MOH’s headquarters that have left pharmaceutical companies in a state of confusion, even anger.

One of the main problems is the delay in procurement of various medications or therapies at the national level, potentially leading to artificial drug “shortages” in upcoming months.

These aren’t shortages in the sense of suppliers failing to supply pharmaceutical products, but red tape in MOH Putrajaya that has befuddled the industry.

“There have been concerns that with a large number of pharmaceutical tenders ending or have already ended, the delay in procuring medicines through new contracts would translate to delays in essential drugs and treatment for patients. There is a real concern that this would result in a drug shortage for certain medications,” a source told CodeBlue.

One of the treatments affected by MOH Putrajaya’s delay in calling for new tenders relates to dialysis for kidney failure, forcing government hospitals to procure supplies through local purchase orders (LPO) as a national tender has yet to be opened.

LPOs can only cover a handful of patients due to limited hospital budgets; it’s also unusual for hospitals to have to rely on one-time local orders so early in the year.

“The hospitals have to be very innovative in their procurement,” another source told CodeBlue. Large centres with many dialysis patients, for example, are requesting smaller district hospitals with fewer patients to use their own budgets to help purchase dialysis products for them.

Nephrologists, pharmacists, and nurses are now dealing with extra paperwork, on top of regular clinical duties, to figure out which dialysis products to purchase, based on the patient’s needs and hospital budget, to ensure continuity of treatment.

“Health care professionals are really concerned because they do not want any casualties. If they don’t have stock, they may not be able to perform dialysis,” said the source. “These are existing patients. What happens when there are new patients?”

Drug Procurement Takes Six To Nine Months

A drug procurement process in the government takes at least half a year. Even if MOH Putrajaya were to open a tender for dialysis products today, it would take six months for the tender to be awarded, according to the source, adding that the supplier can deliver the dialysis product within 14 days following the award of the tender.

Other sources, however, said it would take much longer to import medicines in general, following six to nine months for a tender to be awarded.

“Orders may take several months to prepare as there will often be no ready stockpile available in-country. They will need to be delivered from other countries such as Europe, China, Egypt, or India,” a source told CodeBlue.

“Buying pallet loads of medicines is not like participating in a supermarket buying club, pushing a trolley down the aisle. There are agreements to be signed, orders to be made, and deliveries to execute. They take a lot of time.”

Besides delays in opening new drug tenders, MOH Putrajaya has also allegedly called for renewed tenders “very late”, such as close to a month to the end date of a previous tender.

“There’s a limitation in procurement when the tender lapses; hospital guys are complaining,” said another industry source.

The source noted that LPOs can only go so far as a hospital’s budget for this may be RM50,000 a year, for example, whereas a month’s worth of drugs can perhaps cost RM200,000.

LPOs may also be up to three times more expensive than procurement made at the national level, due to the much smaller volumes purchased.

MOH Procuring 100% To 200% Costlier Generics Than Branded Drugs

Another major procurement issue is the MOH’s decisions over the past six months to a year to purchase locally made generic medications that were two to three times more expensive than off-patent innovators.

CodeBlue understands that for at least three products – medicines used for atrial fibrillation, breast cancer, or post-surgery pain relief – the MOH procured the generic versions at 100 to 200 per cent higher prices than the branded drugs.

“We heeded the government’s call for lower prices. Since the drug was off-patent, we reduced prices, so why on earth did the government buy generics?” an industry source told CodeBlue.

Another industry source said: “There is no level playing field now. You say you want lower prices, but when we give you cheaper, you still don’t want it. So what’s your criteria? You’re not being transparent.”

The source questioned if the government was prioritising local pharmaceutical companies over people’s health, saying: “Local manufacturing is an economic priority, not a health care need. Is MOH prioritising the economy or health care?”

The MOH allegedly did not even invite pharmaceutical MNCs to bid for certain tenders that were opened instead only to local drug manufacturers; at least two MNCs were affected by these exclusions.

A third industry source questioned why certain local generics manufacturers were allowed to submit bids after tenders were closed.

The MOH’s double supplier mandate in pharmaceutical procurement has also come into question, as the source pointed out that tenders aren’t split equally between generics and innovators, despite the ministry’s purported aim of boosting medicine security through its requirement for at least two suppliers.

“Instead, generics to innovators are either 70:30 or 75:25 – what’s the basis for it?”

Some industry sources took issue with the Skim Anak Angkat (SAA) or Skim Panel Pembuat Bumiputera (SPPB) programmes in the pharmaceutical sector that aim to boost the capacity of Bumiputera manufacturers.

Certain companies under the Anak Angkat programme allegedly won drug tenders via direct negotiation as tenders were not advertised, affecting not just MNCs, but also local generics manufacturers.

“I don’t even have a chance to give you my price,” one source complained.

SAA/SPPB isn’t new, having existed under previous administrations. According to a 2021 public consultation paper by the Ministry of Finance (MOF) for the 2022 budget, items under the Approved Product Purchase List (APPL) – the government’s branded and generic drug and medicine supply – can be directly procured from companies in SAA or a few companies under SPPB.

MOF Stops Displaying Value Of Competing Bids In Drug Procurement

Another source of industry dissatisfaction is the MOH sometimes not fulfilling the quantity contracted in drug tenders, be it branded or generic medicines, with the ministry ending up buying less than what was initially agreed upon.

“It’s quite scary for us. We’ve already put in our orders, which we have to put in four to six months in advance. Suddenly, they don’t buy everything,” the source lamented.

“Some companies have very big business in government and have no capacity to sell to the private sector, so they’re stuck with the stock.”

Since the start of the year, the MOF reportedly stopped publishing, on the government’s ePerolehan portal, the value of competing tender bids submitted in medicine procurement, displaying just the winning company and its tender value.

“We’re all angry that we can’t see the pricing,” an industry source told CodeBlue.

“Previously, if say five companies bid on a tender, we would know if we were the most expensive or the cheapest.”

Another source said the lack of transparency in the government’s drug procurement has caused anxiety in the industry.

“Now everyone is jittery. The general environment is uncertain due to the opaqueness of the drug procurement process.”

Pharma MNCs Reluctant To Launch New Drugs In Malaysia

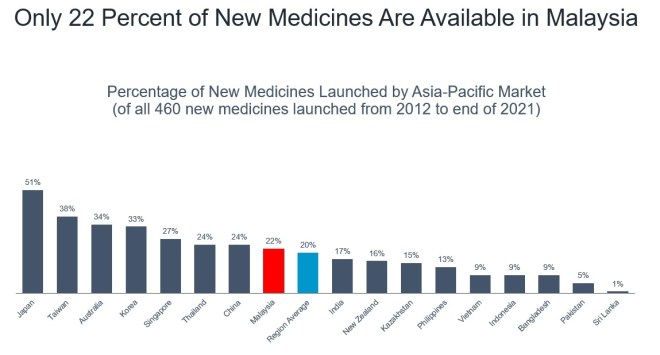

Percentage of new medicines launched by Asia-Pacific market (of all 460 new medicines launched from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

Percentage of new medicines launched by Asia-Pacific market (of all 460 new medicines launched from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

The MOH’s perceived procurement strategy in prioritising local over imported pharmaceutical products – even if imported (branded) medications are cheaper than locally made (generic) drugs – may disincentivise pharmaceutical MNCs from launching new products in Malaysia.

One drug maker, an industry source noted, only launched one product in Malaysia in the last five years, but 20 products in other countries. This particular pharmaceutical MNC is reportedly upset at the MOH over the “lack of transparency and fair practices in tender issues.”

“Companies are already saying they don’t want to launch new drugs in Malaysia for the next five years,” the source told CodeBlue.

“By squeezing MNCs, MOH is making the latest drugs unavailable in the country. You talk about accessibility and affordability, but you’re forgetting about availability.”

“The impression is that it’s getting increasingly hard to do business in Malaysia. As a small market compared to the rest of the world, we stand to lose from not getting new medicines in future.”

Pharmaceutical MNCs are also reluctant to build manufacturing facilities in Malaysia due to these perceptions: lack of talent, poor incentives, difficulty in getting early approvals, challenges for early access, too much bureaucracy, practices are “not transparent”, the government not understanding what businesses need to succeed, increasing inclination towards halal regulations, an inefficient economic development board compared to Singapore, and intellectual property (IP) protection not being a priority.

“I’m so fed up,” said the industry source.

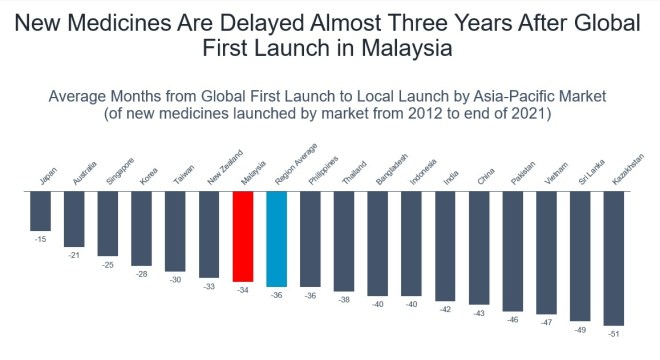

Average months from global first launch to local launch by Asia-Pacific market (of new medicines launched by market from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

Average months from global first launch to local launch by Asia-Pacific market (of new medicines launched by market from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

According to the most recent data from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), as sighted by CodeBlue, only 22 per cent of new medicines are available in Malaysia.

New medicines are delayed nearly three years in Malaysia after global first launch. Only 2 per cent of new medicines are launched in Malaysia within one year of global first launch.

Another source stressed the importance of predictability, reliability, and trust for building and growing businesses in any country.

“If countries are seen as risky and unpredictable markets for investment, for trade, and for business, they are less likely to see registrations and launches of new pharmaceutical products, to be locations for clinical trials, and places for research and development (R&D) for pharmaceutical innovation. They are all linked.”

Percentage of new medicines launched within one year of global first launch in Asia-Pacific by market (of all 460 new medicines launched from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

Percentage of new medicines launched within one year of global first launch in Asia-Pacific by market (of all 460 new medicines launched from 2012 to end of 2021). Graphic from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

Malaysian Generics Manufacturers Face Stiff Competition From China

Foreign drug makers aren’t the only ones frustrated with the government’s medicine procurement practices, but also some local generics manufacturers.

Two sources complained about the lack of government support for the local pharmaceutical industry, amid increasingly stiff competition from China.

One big concern is the APPL listing of medicines from China and India that undergo blistering in Malaysia with very small local companies. These products are sold to the government at very competitive prices.

“Local manufacturers find it very hard to match Chinese drugs,” the source told CodeBlue, describing generic medicines from China as being both very affordable and high quality.

“These Chinese products are winning MOH tenders.”

For the past few years, the government has been importing generic medicines from China that are “way cheaper” than locally made products. Malaysia’s pharmaceutical industry faces difficulty competing with such low prices enabled by China’s economies of scale and subsidies for local manufacturers.

“Our government should subsidise the local operations of generic manufacturers,” the source said.

“If we want health security, we need to create an ecosystem for it. Then we can create an export market, like how we export semiconductors. The pharmaceutical industry is health security.”

Bangladesh Pharmaceuticals Two Decades Ahead Of Malaysia

Another industry source described lower prices for off-patent innovative medicines as “predatory pricing” by foreign drug makers.

The source related how a local company invested RM40 million into R&D for the generic version of a targeted therapy and offered the cancer drug at nearly cost price, but the MOH ended up purchasing the MNC’s cheaper off-patent innovator a few years ago instead.

“For new drugs where generic players just finished spending money on development and new equipment, among others, they will not be able to compete with predatory pricing,” the source told CodeBlue.

“The government needs to decide – do you want this industry or not? If you don’t want this industry, then you can just buy imported generics from India and China. Just tell generic players in Malaysia, ‘the government will no longer support you’.”

Global pharmaceutical companies are able to subsidise their off-patent drugs from the profit of patented products, the source said, citing how the United States sales of Novo Nordisk’s blockbuster weight loss drug Ozempic alone exceed all generic medicines sold in that country.

The source explained that generics manufacturers in Malaysia cannot make much money exporting to other countries, unlike countries like Bangladesh that is a major generics exporter, including to highly regulated markets like the European Union and Australia.

“Bangladesh pharmaceuticals are 20 years ahead of our pharmaceuticals,” said the source.

“In Bangladesh, the government knows how to support the industry. In Malaysia, they say in front of players that they support generic, but behind closed doors, we know they’re best friends with the MNCs.”

Although Malaysia’s total global export value of pharmaceutical products at US$680 million in 2024 exceeds Bangladesh’s US$177.4 million in pharmaceutical exports (between July 2024 and April 2025), the source described Bangladesh’s pharmaceutical sector as more strategically advanced than Malaysia despite a lower absolute export value.

“Bangladesh created a homegrown pharma ecosystem, backed by government, financing, and local ownership, whereas Malaysia has no equivalent long-term pharma industrial policy and most of the market is dominated by foreign multinationals and imported drugs,” said the source, adding that Bangladesh is even self-sufficient in its medicine needs, unlike Malaysia.

The industry source suggested that under the government’s off-take policy, the local generics industry should divvy up drugs that will soon go off patent so that each company can focus on developing one product. Then MOH can procure the generics for a certain period, say five years, at a price agreed on beforehand.

“Local players will then be able to calculate their R&D cost and plan accordingly,” said the source.

“If not, everyone will be fighting over one or all products, spend RM5 million on R&D for each product, fight in the market, and then the MNC does predatory pricing.”

The source cited China that may have at least 20 factories manufacturing the same amount of metformin (a medicine used to treat type 2 diabetes) in a day that is produced by Malaysia in a year.

“Our market is too small; liberalisation never helps the small players. At the end of the day, it’s about volume. Pricing is always about volume.”

A third source observed insufficient interest or investment in local manufacturers to produce drugs needed for conditions, such as rare diseases, that would involve low volume but high cost to produce.

“Local manufacturing also does not necessarily mean that it prioritises local supply. The huge RM2 billion insulin manufacturing facility in Johor, for example, is more focused on export over local supply.”

The source stressed that Malaysia cannot locally produce every single generic or biosimilar drug needed. “We will need patent and off-patent medicines for all the different diseases that we encounter and treat.”

Be Transparent About Trade-Offs In Pharmaceutical Procurement

Governments can decide on what trade-offs to make in medicine procurement, but they should be transparent in their decision-making, an industry source told CodeBlue, in response to the reported purchase of far more expensive locally produced generics than off-patent innovators.

“What the government is really procuring is not a product then; what the government is procuring is security. Therefore, it’s putting a value and a premium. So then they should say it. And that’s okay.

“Then everybody who’s competing knows that they’re not competing for a product necessarily; they’re competing for security,” said the source.

The source, however, stressed that what might give the government security today might not be the right thing for public health in the long term. For example, a pharmaceutical company builds a factory in Malaysia to make a certain medicine for a certain disease, but a more effective therapy emerges in the next three years.

“Should I then win the contract purely because I have built a factory even though it’s no longer the most clinically effective thing? So the question is – what is security? Is it security of supply today or is it security of consistent supply of the best possible science for the next 10 years?

“That’s a policy choice. There’s no right, there’s no wrong – there’s just a choice. As you make that choice, people should be comfortable with that choice.”

The industry source defended “well-intentioned” policymakers who have the difficult task of balancing various trade-offs in budget and clinical decisions.

“How do we continue to create a healthy environment where all of these conversations can happen openly, transparently, and robustly, so that the whole country continues to move forward?”

The industry source also praised Malaysia’s pharmaceutical ecosystem.

“I think MOH and government officials are trying very hard. Public health is not easy. Managing the health of the public is not easy. I think Malaysian clinicians are good and doing well.

“I think hospital leaders and administrators have a very difficult task and I think they’re doing really well. And I think the budgetary community and Ministry of Finance are also doing well.”

When contacted about the various drug procurement issues, the MOH’s corporate communications unit simply told CodeBlue that the ministry was unable to comment because “policy on procurement is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance.”