There are still remnants today of the city’s pre-war tram network The “Tramways Centre” in the 1930s(Image: Mirrorpix)

The “Tramways Centre” in the 1930s(Image: Mirrorpix)

An underground would cost too much, buses may never be a mass transit solution, and new stations will only see a few more trains a day. So the answer to Bristol’s decades-old demand for the kind of transport network visitors to Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh and Nottingham see every day, is increasingly being touted by those now in power in the city – trams.

The city council is gradually creating key transport routes that could, they say, one day accommodate trams. But trams are nothing new on the streets of Bristol. The city was one of the first in the country and indeed the world to install a tram network, and at its heyday it was the envy of many other cities.

The transport planners of the 2020s, and let’s be honest, probably the 2030s, are earmarking routes for what could end up being a tram system for Bristol’s future. They include Cumberland Road along the north side of the New Cut, the A4 through Brislington, and the A4108 out through Clifton and Westbury-on-Trym up to Cribbs Causeway.

But, as the previous Labour administration run by Mayor Marvin Rees pointed out, Bristol could struggle to put trams back on main roads where they used to be, like the A38 Gloucester Road through Horfield and Bishopston, the A420 Church Road to Kingswood through St George and Redfield, or the A38 through Bedminster, simply because there are hundreds and hundreds of times more vehicles on the roads now than there were at the turn of the 20th century.

Trams were the main means of getting around the city for Bristolians from the last decades of the 19th century and up to the eve of the Second World War.

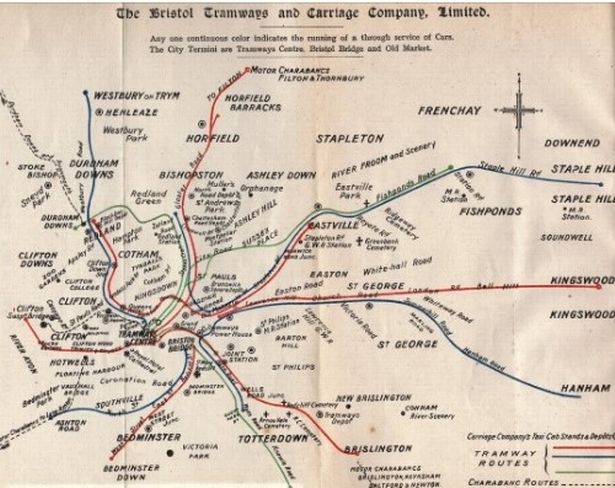

By 1910, the city was criss-crossed with routes coming from all quarters, with pretty much every main road into the city centre containing two-way tram lines. One of the longest routes started in Staple Hill, came down Fishponds Road, then Stapleton Road before swinging right at Broadmead and heading up Gloucester Road to terminate at Zetland Road and the Arches.

The 1910 map of Bristol’s tram network(Image: Visitors’ Guide to Bristol + Clifton, Bristol Tramways & Carriage Co. 1911)

The 1910 map of Bristol’s tram network(Image: Visitors’ Guide to Bristol + Clifton, Bristol Tramways & Carriage Co. 1911)

Another route from Eastville went through the city centre but then climbed the hill to Kingsdown and ended at the Downs. Fares were cheap, the trams were usually bustling, and provided Bristolians with a way to get around the city, commute into the city centre and also for leisure.

One route took Bristol City fans from the city centre to Ashton Road outside Ashton Gate football ground, while another went from the centre up Gloucester Road with a stop close to the Memorial Stadium for rugby fans. Three tram lines served Bristol Rovers’ Eastville stadium, including one that went west into St Werburghs and St Pauls.

Most routes terminated at the Tramways Centre, a vast open space over the recently covered River Frome and St Augustine’s Reach. It wasn’t the centre of the city as such – that was still the warren of shops, homes, businesses and churches on the west side of Bristol Bridge – but those streets were too narrow and crowded to put trams through. So, the lines from the south stopped at Bristol Bridge, and the ones from the north, west and east skirted around the old city, went through Broadmead and stopped at the Tramways Centre.

This is why, to this day, this area is still known as The Centre. The last tram ran on the morning of Good Friday, April 11, 1941, and even though that was now more than 84 years ago, there are still reminders of the city’s tram network if you know where to look – as well as the name of The Centre.

The Tramways Generator building, built in 1895 to power the Bristol Tramway network, it fell into disrepair but was restored into new offices in the early 2020s(Image: Google Maps)

The Tramways Generator building, built in 1895 to power the Bristol Tramway network, it fell into disrepair but was restored into new offices in the early 2020s(Image: Google Maps)

The biggest is to be found on the west bank of the Floating Harbour on the Redcliffe side of St Philips’ Bridge. The huge redbrick building, recently saved and converted into swanky offices, was built to power the trams when they switched from horse-drawn to electric in around 1895.

Known as the Tramways Power House, or the Generator building, it survived the war – just – and was built next to a huge brewery.

There are others too. Anyone walking up Bedminster Down Road away from the Miners Arms towards the second railway bridge might not have noticed some public toilets on the left hand side of the road, and an unusually wide junction with a side road, Trafalgar Terrace. This was the last stop on the route that went up the A38 into what was then the edge of the city, at the railway line.

READ MORE: The almost 70 year history of Bristol’s tram networkREAD MORE: Bristol could get a tram line as city centre road changes leave ‘unbroken’ path

Some track also survives to this day – patients at the Gloucester Road Medical Centre step over two lengths of track in the car park, and there’s also some bits of track on the wide ramp approach to Temple Meads station.

In St Mary Redcliffe Church, there is a monument which tells the story of the demise of the tram network. The Tramway Rail Monument is a piece of the tram rail that was left embedded in the churchyard ground at an angle after it was hit by a bomb on nearby Redcliff Hill.

The road and the tramway rails were blown to pieces, and one flew up and impaled itself into the ground.

A piece of the tramline landed within the churchyard at St Mary Redcliffe, on Good Friday in 1941, and has remained in place ever since.(Image: PAUL GILLIS / Reach PLC)

A piece of the tramline landed within the churchyard at St Mary Redcliffe, on Good Friday in 1941, and has remained in place ever since.(Image: PAUL GILLIS / Reach PLC)

With some degree of foresight, particularly because scrap metal was highly prized at the time for the war effort, and people were told to sacrifice their front garden fences and railings for the cause, people in Bristol were so impressed at the sight of the tramway rail being embedded in the ground, that it was left as a monument that survives to this day.

It is true that the Second World War killed off Bristol’s tram network, but that’s not the whole story. In truth, by the 1930s, buses began to be the preferred mode of transport for Bristolians. They were more flexible, and bus operators were creative in devising routes that took people where trams couldn’t.

In 1937, the private company that ran the trams passed over control to a civic organisation run by the Bristol Corporation, and in 1938, lines started to close. That closure programme was halted in 1939 because of the Second World War, but it was the Luftwaffe which continued it.

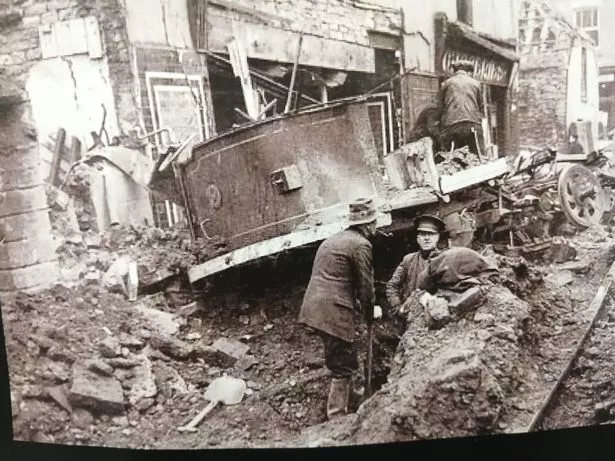

Nazi bombers targeted main road and rail networks in Bristol, as well as the city centre and the factories of Bedminster, St Philips and Brislington.

The aftermath of a Luftwaffe air raid on Bedminster, in which a bomb hit a tram travelling along West Street, outside the White Horse pub(Image: Bristol Archives)

The aftermath of a Luftwaffe air raid on Bedminster, in which a bomb hit a tram travelling along West Street, outside the White Horse pub(Image: Bristol Archives)

One bomb completely destroyed a tram as it passed along West Street in Bedminster, next to the White Horse pub. Another – as stated – destroyed the line in Redcliff Hill, but it was the bomb which destroyed St Philips Bridge on Counterslip in the city centre that stopped the trams completely.

That fell as part of the Good Friday Blitz, on April 11, 1941, which set the centre of Bristol, on the other side of the water, on fire. It severed the power supply from the Tramways Generator building and none of the trams that were out in the city at the time could move. The last one to make it back to the depot was the Old Market to Kingswood tram, which was pushed along the rail by passers-by and freewheeled into the depot.

“Although the generating station was not hit and still stands today, the Bridge was destroyed and had to be rebuilt,” the Evening Post reported at the time. “One tramcar was in Regent Street, Kingswood when the power failed.

The Bristol Tramways would operate for nearly 70 years from 1875 until 1941.(Image: BUP)

The Bristol Tramways would operate for nearly 70 years from 1875 until 1941.(Image: BUP)

“The lights dimmed and went out. The car was adjacent to the Clock Tower and there was nothing Motorman Webster could do to revive his tram. By chance the car was standing on the only section of track running out from Old Market Street to Kingswood that ran downhill to the Depot. Mr Arthur Britton and bystanders with the help of gravity pushed the car to the depot with driver Webster at the controls, free wheeling into the depot.”

The tram company continued as a bus operator, which became the Bristol Omnibus company, but the trams never ran again.

Is bringing back trams the solution to Bristol’s transport issues? Let us know in the comments section below