The most that can be said with honesty about this hefty book by Orhan Pamuk is that it contains pretty illustrations and is beautifully produced. Between the years 2009 and 2022, we are told, Pamuk journaled his daily life, observations, and thoughts in visual and verbal modes. These were recorded in notebooks: written notes together with vivid illustrations that were largely focussed on the landscape of the place in which he happened to be staying.

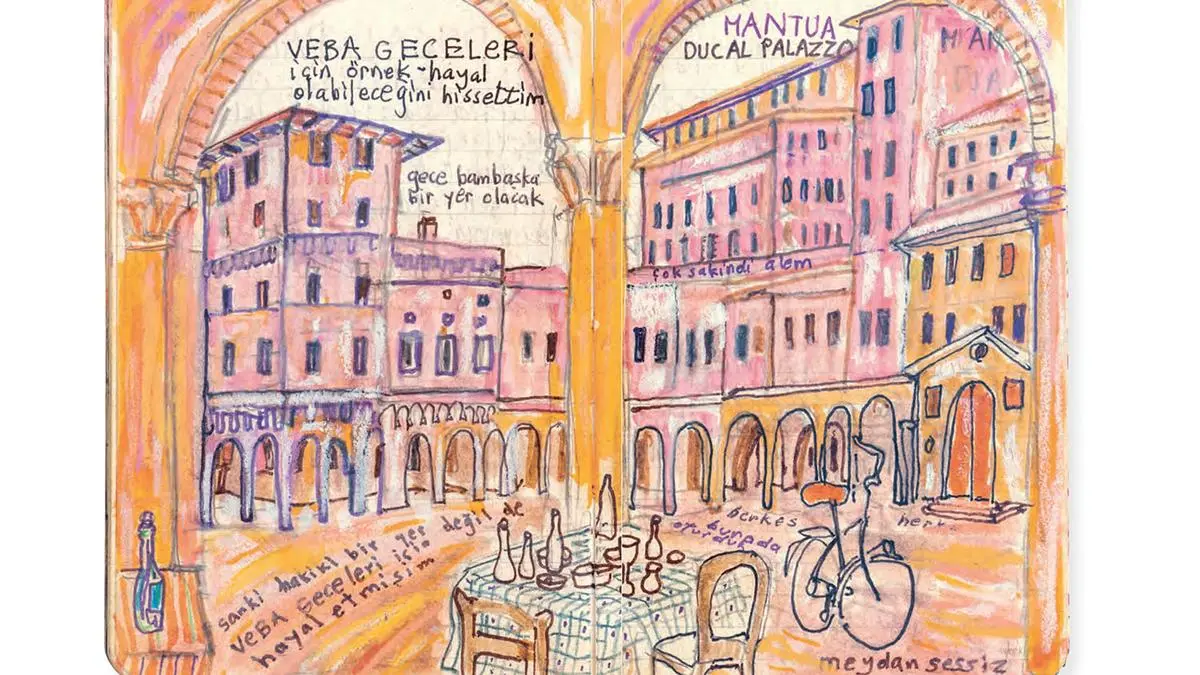

As a writer, Pamuk is hugely in demand and appears to lead a peripatetic life around the globe. The notebooks, he tells us, accompany him everywhere and are an integral part of his creative self. The present book is a non-linear compilation of selections from these records. Written into the margins of the paintings that occupy the centre spread are the internal monologues on his day, his travels, his family, the food he ate/cooked/served, the frustrations over the logistics of the museum he worked on for a long time, his short ruminations on the novel currently in progress, or the writer’s block he often struggles with, and of course, his vexed relationship with his homeland, Türkiye, that also finds expression in a number of novels, as readers of Pamuk’s fiction will know.

Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks, 2009-2022

By Orhan Pamuk, translated by Ekin Oklap

Hamish Hamilton PenguinPages: 378Price: Rs.1,299

What is the purpose of publishing yet another personal document by Pamuk, whose published works already include the autobiography Istanbul: Memories and the City? We are told that he always dreamt of becoming a painter:

“Between the ages of 7 and 22, I thought I was going to be a painter. At 22, I killed the painter inside of me and began writing novels. In 2008, I walked into a stationery shop, bought two big bags of pencils, paints, and brushes, and began joyfully and timidly filling little sketchbooks with drawings and colours. The painter inside of me hadn’t died after all. But he was full of fears and terribly shy. I made all my drawings inside notebooks so that nobody would see them. I even felt a little guilty; surely this must mean I secretly deemed words insufficient. So why did I bother to write? None of these inhibitions slowed me down. I was eager to keep drawing, and drew wherever I could.”

Also Read | Queen’s gambit

Perhaps it was the urge to show the drawings to the world, despite the initial shyness; perhaps it was the remarks of random people who praised the paintings that acted as the inducements. Whatever trigger led to the publishing of this book, it certainly could not have been the writing, such as it is. Mere jottings of the highlights of the lived day, these entries are likely to strike the reader as dull and brief, opaque and repetitive.

Vanity project

Shorn of animated investment, each day as recorded in the book proceeds much like the one before or the one after. Jean-Paul Sartre would agree that banality marks existence, and Pamuk’s jottings reproduce the banal substratum, the dregs of lived time. The absence of a narrative and, for those who do not know much about Pamuk the person, the lack of courtesy in not introducing the reader to the various people he meets, lives with, or bumps into turn these monotonous notes into so much undigested information.

The little notes on his own writings and of others he meets or whose works he teaches (of Joseph Conrad, for instance) are either nondescript and non-committal, or incomplete assertions that are never substantiated. The jottings on the cultural/literary festivals he travels to as an invited speaker, such as the Jaipur Literature Festival in India, read like a list of who’s who in the literary field. We get bland, one-line descriptions of the stars that speak of a colossal authorial indifference.

Memories of Distant Mountains seems like the self-indulgence of a privileged male writer at the height of his fame.

| Photo Credit:

By special arrangement

The inexplicable decision to organise the selected miniatures in a non-linear, “Emotional” (as Pamuk puts it), order adds to the reader’s confusion. The frustratingly non-chronological jumble is bound to bewilder the reader who may, not unreasonably, expect reproduced diary entries to follow the order in which they were first recorded. If it is memory that forms the basis of the re-ordering, the writing and/or the illustrations need to necessarily encode an emotional structure, map the coordinates of the creative process, as it were, to guide the tenor and mood of the organisation.

Neither the vapid writing nor the pretty pastel miniatures allow a peek into the writer’s mind. In an early entry, Pamuk records: “Before I die—I would like to write a book called distant mountains. A book about painting and imagining distant realms and misty mountain scapes.” This book faithfully executes that early wish: title, painting, distant mountainscapes, all boxes tidily ticked. Memories of a Distant Mountains seems more like a vanity project, the self-indulgence of a rather privileged male writer at the height of his fame and literary reputation.

Also Read | Izmirli: A novel on the psychology of love

An internationally well-regarded daily has called out the work as a testament to the writer’s oversized ego; another wonders whether this is “the most embarrassing book published in modern times by a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature”.

Readers will have to balance such views and their own response to the memoir against a vast majority of reviews that happen to be, not surprisingly, eulogistic.

Rohini Mokashi-Punekar teaches literature at the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati. Her latest book is The Third Eye and Other Works: Mahatma Phule’s Writings on Education (2023).