Taylor Swift recently made headlines when she purchased back her musical catalogue, after re-recording masters that shot to the top of the Billboard charts. Swifties collectively understand that ownership equals control, and that to be in a position of not having control over your work is somehow sad, and merits economic allyship.

These headlines about the popstar coincided with anxieties about “ownership” north of the border, too, as U.S. President Donald Trump began threatening annexation with his “51st state” comments. “Canada is not for sale” declared Prime Minister Mark Carney during a visit to the White House.

Canadian book buyers who happily hem and haw over labels at the grocery store seem blissfully unaware of the elephant in the room— that 95 per cent of the Canadian book market is already controlled by foreign-owned multinational publishers.

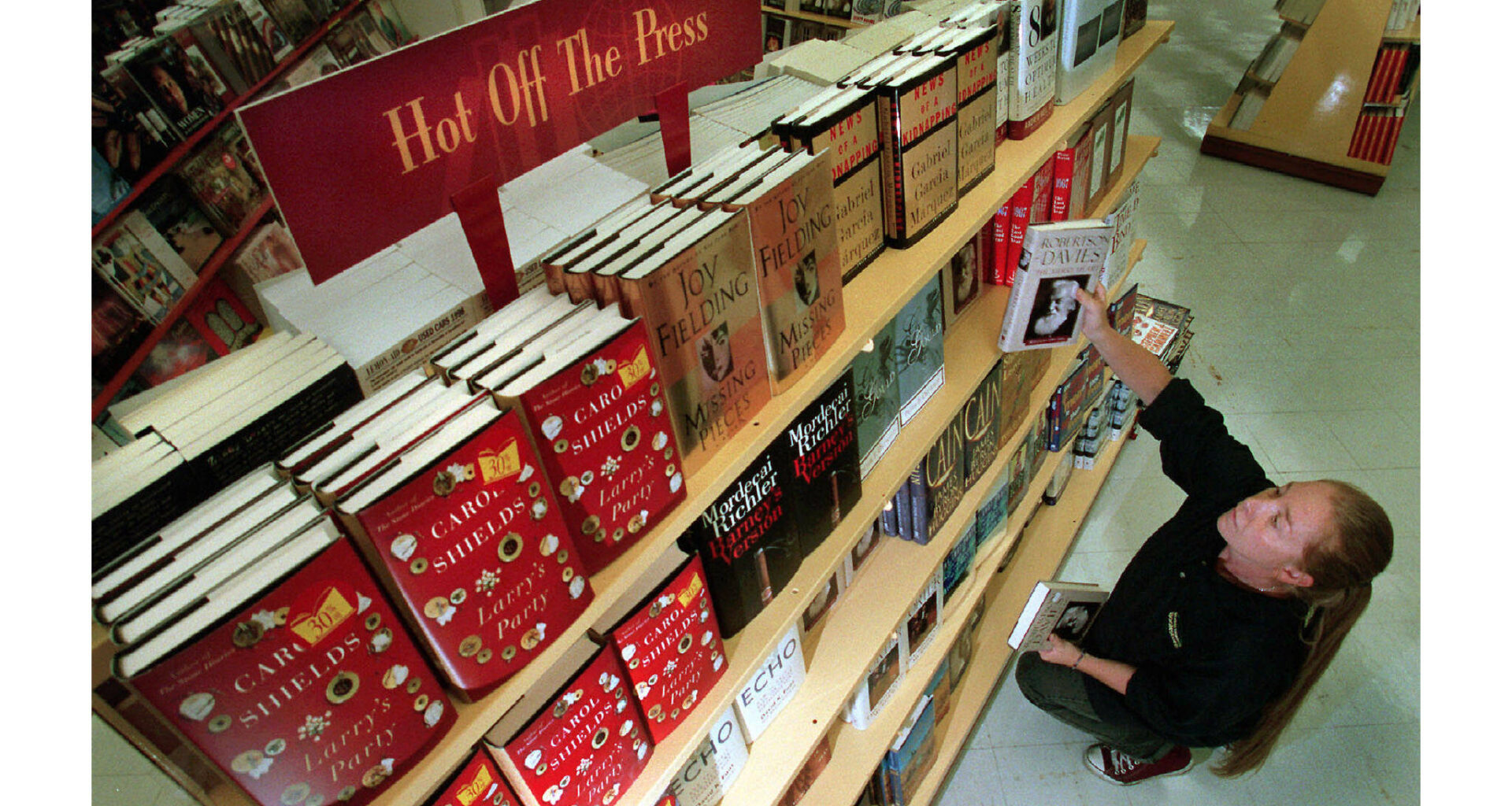

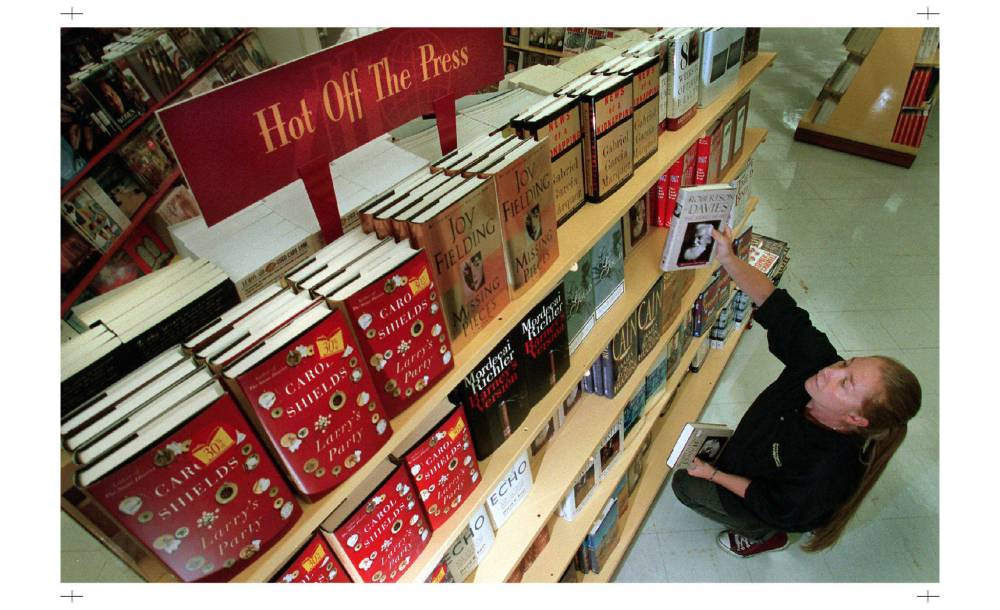

Trying to keep from buying American products? Consider who is publishing the books you’re reading. (The Canadian Press Files)

Mark Carney’s “Values” was published by the Canadian branch of Penguin Random House (headquartered in New York City, themselves a holding of German-owned Bertelsmann), so was Wab Kinew’s memoir, “The Reason You Walk.” I don’t blame the authors.

Multinational publishing houses offer them a megaphone that amplifies their work a thousandfold. For the biggest names, the most Book-Tok-worthy titles, and the lucky few who are published by the branch plants, their advances (money offered upon signing a contract, before a book is published) far exceed what Canadian independent publishers can offer. Books published by The Big Five (Penguin Random House, Harper Collins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette and Macmillan) are regular fixtures on awards and bestseller lists, so my quarrel isn’t with the books themselves, or with their authors, or even with the people who work on those books in the glass towers of Toronto offices. It’s with those Five’s complete and utter dominance of the publishing industry.

Roughly 115 independent English-language publishers operate in Canada. According to the BookNet report “The State of Publishing in Canada 2023,” Canadian companies published an average of 35 books in 2023, while multinationals published an average of 752 books — a few token Canadian-authored titles, and a veritable firehose of books authored elsewhere, distributed into Canada, and marketed with budgets that far exceed those of their Canadian-owned and operated “competitors.”

So why, when branch plants exist, are indies important at all? Indies push the envelope. As an industry, we have a collective track record of recognizing cultural and historic value before multinationals recognize the commercial potential of the same authors/topics.

Debut authors are risky, while those with an existing platform represent a surer return on investment. University of Manitoba Press published John Milloy’s A National Crime in 1999 — years before truth and reconciliation became part of the national discourse. Even working at a small university press, I’ve seen agents and editors browsing our digital review copies and buying from our website. I met a Big Five editor recently who came to our booth at a conference book fair, no doubt scoping out the university presses to see if any titles held trade-crossover appeal.

I don’t doubt the intentions of the editors and publishers working for the branch plants. They’re doing good work. But at some point, the further up the chain you go, somebody’s (likely New York-based) boss cares more about shareholders than readers. In the book business, which teeters on razor-thin margins, and in a country where the total population is roughly the size of a single U.S. state (California) — that’s a dangerous problem. To be a branch is to be vulnerable. As any arborist will tell you, you don’t make cuts from the trunk.

To be sure, fears over foreign ownership are long-lived and perhaps easy to dismiss as nationalistic pearl clutching, but I question whether the C-suite has any sort of genuine concern for the cultural value of stories from Canada. Valuations are more central to their philosophies.

The Big Five all have far-right imprints under their domain, suggesting that the corporate powers-that-be are equal opportunists when it comes to ideology. Just look at the websites of imprints Forum, Signal, or Broadside Books: their author lists read like a veritable who’s-who of American conservatism. If book buyers seek out a Canadian-authored book published by a branch plant — in the same spirit of “sticking it to the man,” that one might select a Canadian alternative to Cheez-Its — I’m afraid they are putting their loonies far closer to the regime most of us are trying to resist than if they had indulged their cravings at the grocery store.

I spent much of my 20s working in the Toronto office of an American-owned multinational education publisher. During my years of service, I watched that company shrink as subsequent restructurings designed to “optimize” and “introduce efficiency” shuttered first the warehouse, then the trade division, then accounting, then the Higher Ed Division’s Canadian editorial department, and eventually closed the office, leaving a handful of sales reps scattered across the coun-

try, whose job is now mostly to sell American textbooks to Canadian students.

Talk to anyone at a multinational publisher — education or otherwise — you’d be hard pressed to find a branch plant that hasn’t been restructured in the last decade.

The once venerable bastion of Canadian literature, McClelland and Stewart — copyright holders of the works of Margaret Atwood, Leonard Cohen, Michael Ondaatje and Mordecai Richler (to name but a few) is now an imprint of Penguin Random House. They continue their rich tradition of publishing great Canadian writers, but they’re doing so in much smaller numbers than they once did.

Where once they published a list of more than 100 books per year and were leaders in publishing new Canadian voices, their Fall catalogue boasts 17 currently announced Canadian-authored titles — nine of which are by Margaret Atwood. For the C-suite, valuations proceed values — and they always will. That imprint recently announced an exciting forthcoming title, a “Elbows Up,” ostensibly a collection of reflections about Canadian sovereignty from a collection of well-known Canadians (including Margaret Atwood — so make that 10/17.) The irony of a multinational publisher issuing this work was lost on all who excitedly commented on the social media announcement, pledging their Canadian pride and promising to order a copy.

Canadians do not own the bulk of their cultural output. Our stories are not our own.

To be sure, the Big Five are unlikely to exit the Canadian marketplace any time soon. Their books (Canadian-authored and otherwise) will continue to dominate Indigo shelves, media coverage and bestseller lists. Indie publishers will continue to do the important work of lifting debut and midlist authors, and doing so in a marketplace that does them no favours.

But if mention of the 51st state churns your stomach enough that you make choices at the grocery or liquor store, consider adding an independently published book to your summer reading list.

» Stephanie Paddey is the sales and marketing supervisor at University of Manitoba Press.