Every sport has gray areas to be exploited. The athletes who exploit them are often described as engaging in the dark arts: not necessarily breaking the rules, but pushing them to their limits.

Every sport needs an avatar for this, whether it’s Sergio Busquets s—housing in soccer, the MLB Houston Astros sign-stealing scandal or Diana Taurasi in the WNBA. Tennis has had plenty of them down the years, and now one of them is in the Wimbledon quarterfinals, wearing the badge with pride.

Laura Siegemund faces tournament favorite Aryna Sabalenka, in what feels like the ultimate test of the world No. 1’s supposedly newfound serenity after her French Open final defeat to Coco Gauff last month.

Siegemund, who plays an awkward, slice-heavy game with changes in speed and plenty of drop shots, has also developed a reputation as one of the sport’s trickiest opponents.

In her fourth-round match against Argentina’s Solana Sierra, a 21-year-old lucky loser playing in her first last-16 match at a Grand Slam, Siegemund started the contest by letting her opponent’s nerves marinate that little bit more. She turned up for the match around five minutes late, leaving Sierra to stand around awkwardly and wait.

Once it started, Siegemund, who will be competing in a Wimbledon quarterfinal for the first time at age 37, showed why she is one of the slowest players on the tour, taking as much time as possible between points and pausing in her service motion for a couple of seconds each time. She also changed her racket frequently, even during games, which helped to disrupt her opponent’s rhythm.

“I think part of her game is to find out how to irritate the other person a little bit,” Naomi Osaka said of the German in 2018. And if Siegemund wins a key point Tuesday, Sabalenka will know about it — she is happy to get in her opponent’s face, figuratively speaking, at big moments.

She is an intriguing character, and perhaps most revealingly of all, the holder of a psychology degree. WTA insiders have long felt that this has helped her ability to read her opponents and know what will get under their skin.

Siegemund insists that this is not all part of her plan.

“I mean, these are some matches where, you know, things happen. I don’t necessarily like or seek to make trouble, that’s not my goal,” she said in a news conference Sunday. “I know that I have some very controversial habits. I don’t try to disturb anyone, although that might be interpreted like that.

“I have my weird stuff going on. I’ve been doing it all my life. I was always slow, talking about time violations and stuff. That’s nothing that just got invented now. I’m pretty consistent with my weirdness that I have. I do it for me and not against other ones, but it does lead to confrontation sometimes. Then I’m just, like, ‘Well, that’s how I am’.”

She added that she will not back down for anyone, including Sabalenka: “I don’t change my time or how I behave on the court depending on who I have on the other side.”

One person’s dark arts is another person’s not showing a top player too much respect, of course. The sport has arguably become too deferential, with players often appearing in awe of its legends, especially when they face them across the net.

Some players who had success against greats such as Rafael Nadal were willing to engage in the dark arts. Robin Söderling rattled the 22-time Grand Slam champion during a five-set defeat at Wimbledon in 2007, by mocking his slow play and habit of fiddling with his underwear.

Two years later, the Swede became the first man to ever beat Nadal at the French Open. “You have to unsettle these guys and stand up for yourself,” Söderling told this reporter in a subsequent interview. “Show your opponent that you believe in yourself and you’re there to win.”

Lukáš Rosol was similarly in Nadal’s face during a shock win at Wimbledon in 2012, and even knocked over the Spaniard’s meticulously organised water bottles during a changeover at the London tournament two years later. The Czech was known to employ other dark arts, once barging into Andy Murray at a match at the Munich Open and then being told by the Scotsman that “no one likes you on the tour. Everyone hates you.”

Those greats engage in them just as much. The service clock was introduced largely because of Nadal’s lengthy rituals between points; Novak Djokovic has long been a master of the rope-a-dope: sowing doubts in a player’s mind about form, condition and mental state even if, underneath the antics, all is quiet.

Greece’s Maria Sakkari expressed similar sentiments Murray’s regarding Rosol during a heated exchange with Yulia Putintseva of Kazakhstan, after their first-round match at the Bad Homburg Open in Germany last month.

Putintseva has irritated players by doing things like taking medical timeouts (MTOs) at, they have argued, deliberately inopportune moments. She also has other ways to get under players’ skin. In a third-round match against Iga Świątek at Wimbledon last year, she repeatedly asked the umpire what was going on while Świątek took a lengthy bathroom break at the end of the second set.

The crowd then booed Świątek when she returned to the court — and she went on to lose the match.

More recently, two-time Grand Slam champion Victoria Azarenka accused five-time Grand Slam champion Świątek of slow play during a match at that same Bad Homburg Open. After Świątek threw the ball up but didn’t serve, instead bouncing it a few more times, Azarenka stopped play to talk to the umpire. “Every time, it’s the same story,” she said. “As soon as she’s down in the game, she’s taking her time. Like, over the time. And you’re not checking. Every time.”

Świątek fans later posted evidence of Azarenka doing the same thing, in the same match, on social media. The internet — and tennis players — never forgets.

Siegemund herself knows what it’s like to have fans turn because of perceived gamesmanship.

In a 2023 U.S. Open match against Gauff, she drew the wrath of the home crowd for her slow play, with her opponent also complaining to the umpire about it.

“I am very, very disappointed of the way people treated me today … they had no respect for me,” Siegemund said in her news conference, after a match in which the umpire gave her a point penalty for persistently taking too long between points. In one sequence in the third set, Gauff appeared to hit an ace on a first serve, but Siegemund threw up her hands, saying that she wasn’t ready. Gauff was forced to serve again and voiced her displeasure over that decision to the umpire.

“She was going over the time since the first set, and I never said anything,” Gauff said. “Obviously, the crowd started to notice that she was taking long, so you would hear people in the crowd yelling ‘Time’ or doing the ‘watch’ motion.”

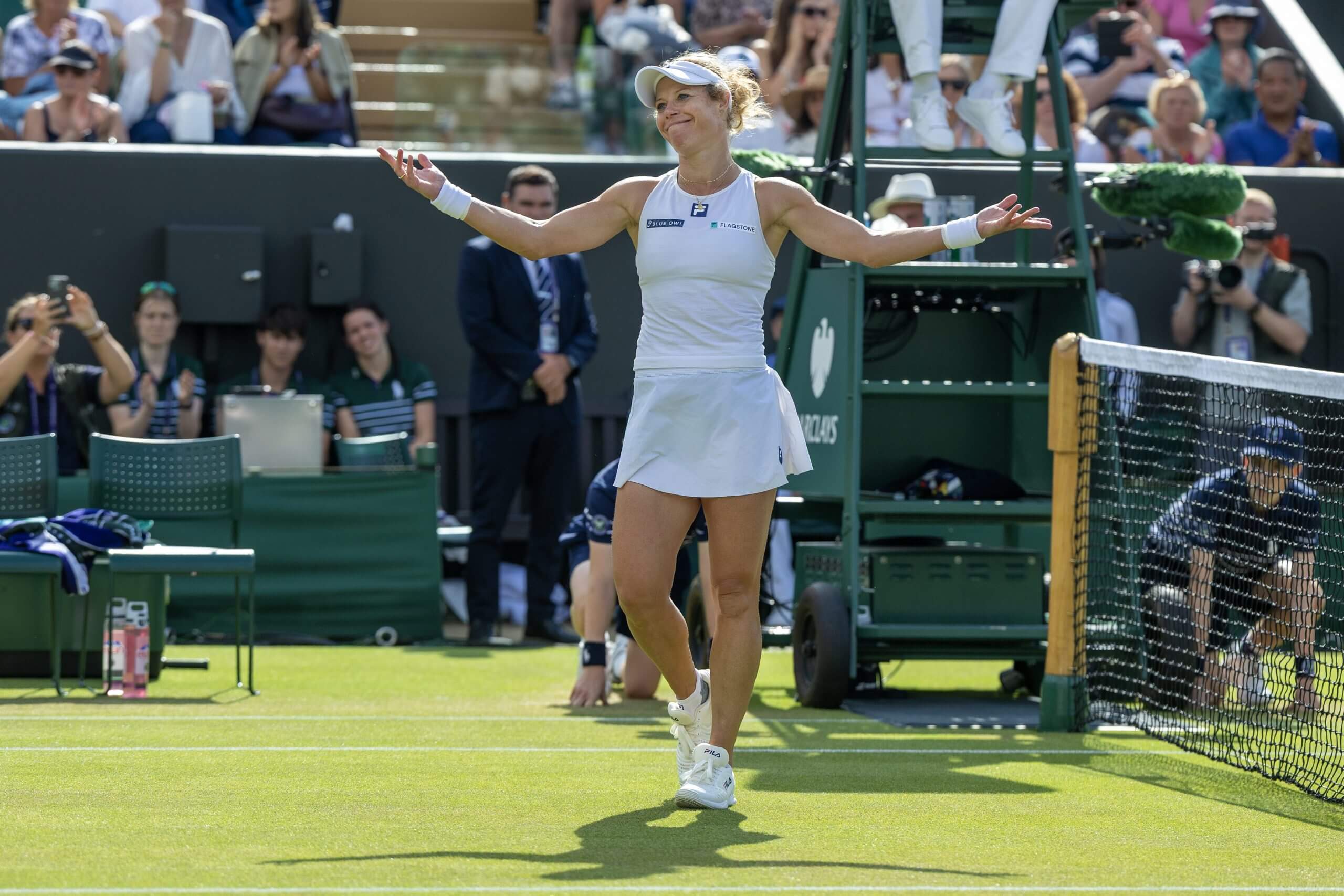

Laura Siegemund celebrates after setting up her Wimbledon quarterfinal against Aryna Sabalenka. (Tim Clayton / Getty Images)

Siegemund could be seen as the heir to Mary Pierce, France’s two-time Grand Slam champion who would take an age between points, almost always using the maximum allotted. During her U.S. Open semifinal against Elena Dementieva of Russia in 2005, as she fiddled with her hair between points, a fan shouted out: “Mary, your hair looks great. Come on!”

In the same match, Pierce called for consecutive MTOs after losing the first set, which took 12 minutes in total, before racing through the next two against her increasingly rattled opponent.

MTOs and bathroom breaks are two of the ripest and most controversial arenas for dark arts in tennis. They are there for good reasons, so players can receive treatment and go off court if required, but they are also available as disruptors to an opponent’s rhythm for the sport’s canniest operators.

Players are not allowed to take MTOs for cramp or for “loss of conditioning” — being tired, in essence — but small injuries and less visible problems that require interventions at tense moments in matches can also unnerve the opponents of those who are suffering from them.

Siegemund has previous on the MTO front with Sabalenka’s good friend Paula Badosa, most notably at a Miami Open match two years ago. On that occasion, Siegemund left the court for an 11-minute bathroom break at the end of the first set, and then had an MTO that lasted 14 minutes in the third. Both were within the rules, but during the latter, the Spaniard hit with a ball-kid to stay warm. She also started celebrating more passionately than usual to match Siegemund’s big cheers, and pointed out her opponent’s slow play to the umpire.

At the same tournament this year, Mirra Andreeva of Russia was furious when America’s Amanda Anisimova took a timeout in the middle of one of her service games. Anisimova later posted evidence of her blistered hand on Instagram.

Britain’s Emma Raducanu was also on the receiving end of some alleged inventive gamesmanship from Zheng Qinwen of China at the HSBC Championships in London last month. Raducanu was serving at break-point down when Zheng stopped play to change shoes, as she had done in her previous match.

It’s generally considered poor practice to do this sort of thing in an opponent’s serving game unless it’s absolutely essential, because of the way it affects their rhythm and concentration. “The fact it happened three times on my serve, I feel like maybe something could have been done, but I’m not going to get into it,” Raducanu said in her news conference.

Players calling each other out for allegedly bogus MTOs has been a part of tennis throughout the 21st century.

One of the most memorable examples came when Russia’s Maria Sharapova questioned the legitimacy of a mid-game one from Ana Ivanovic of Serbia during a Cincinnati Open semifinal in 2014. “Check her blood pressure,” shouted Sharapova, a comment dripping with sarcasm, later on in the set.

With bathroom breaks, the most infamous incident of a player being accused of gamesmanship was Murray and Stefanos Tsitsipas of Greece clashing at the 2021 U.S. Open.

After Tsitsipas took an eight-minute trip to the toilet, Murray said he “lost respect” for his opponent, and during the match even accused him of “cheating”. “It’s not so much leaving the court. It’s the amount of time,” Murray said afterward. “It’s nonsense and he knows it.” Tsitsipas, who did not break any rules, also left court to go to the bathroom at the end of the second set and had a medical time-out for treatment on a foot injury before the fourth.

“Every single time it was before my serve, as well,” Murray said. “Also in the fourth set, when I had 0-30, he chose to go and I think he changed his racket. It can’t be coincidence that it’s happening at those moments.”

Murray also tweeted: “Fact of the day. It takes Stefanos Tsitsipas twice as long to go to the bathroom as it takes Jeff Bazos (sic) to fly into space. Interesting.”

He even referenced the incident in a live theatre show in 2025, underlining how much of a mark these sorts of things can leave on a player.

Some of Tsitsipas’ fellow players defended him, pointing out an underlying principle of tennis’ dark arts: any perceived infringements often demonstrate issues with the rules, rather than with players.

The year after the Tsitsipas-Murray incident, the ATP introduced a new rule limiting players to one bathroom break per match, of a maximum of three minutes, and only to be taken at the end of a set. Players can take an extra one at the slams, where matches are best-of-five sets not three, providing the second one is after the third set.

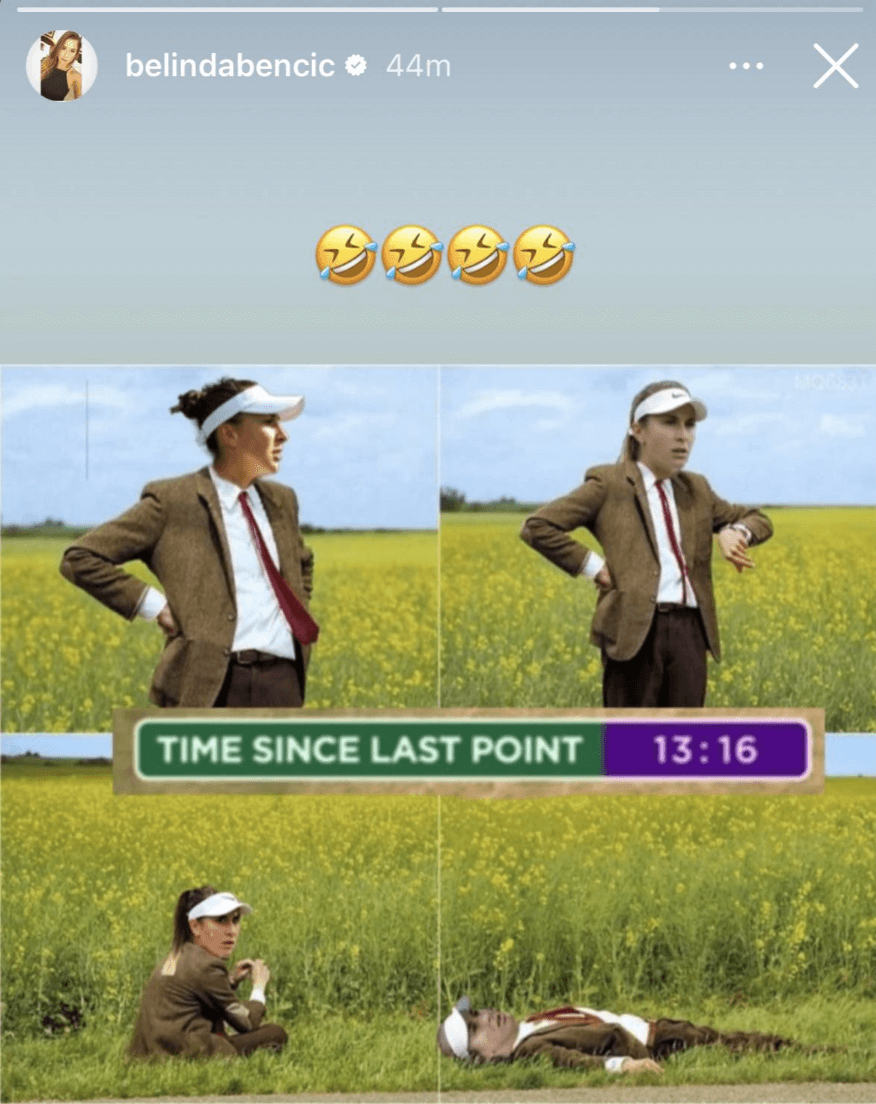

A recent University of Manchester study suggested that bathroom breaks led to a big uplift in sets won by players who had taken them. At this year’s Wimbledon, Belinda Bencic of Switzerland made fun of French opponent Elsa Jacquemot’s 13-minute trip to the toilets after losing the second set of their second-round match with a post on Instagram.

This year’s tournament in south-west London has seen other uses of the supposedly dark arts.

The match Sunday between Britain’s Cameron Norrie and Nicolás Jarry turned into a deliciously passive-aggressive battle, as the Chilean grew increasingly annoyed with how long his opponent was bouncing the ball for between serves.

“Is there a rule? Do you have to intervene or do I have to suck it up?” Jarry said to umpire Eva Asderaki, after Norrie had taken a two-set lead.

“He can stop doing it,” Jarry added. “It’s not a nervous tic, it is something he can control.”

Asderaki replied that she could only intervene if she felt it was a case of deliberate gamesmanship. Jarry replied: “It affects me, so if the rule says you have to do something if it affects me, then do it.”

Norrie bounced the ball 25 times between first and second serves at one point during the second set’s tie-break. Clearly making a point, Jarry bounced it 23 times and kept resetting his stance before serving in the third-set tie-break. A couple of points later, Norrie bounced the ball 23 times. Jarry then took an age between a first and second serve, before Norrie again followed suit.

In this instance, a clear flaw in the rules was being exploited, because while a shot clock was introduced a few years ago to speed up play between points, there’s no clock between first and second serves.

That match also saw a few examples of “tubing”: tennis speak for smacking a ball at an opponent from close range.

Ben Shelton of the United States was accused of this in a doubles match by Andrea Vavassori at the Monte Carlo Masters in April, and responded dismissively, calling the Italian “soft”.

Back at Wimbledon, Russia’s Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova said Sunday that she’d been irritated in her third-round match by Japanese opponent Osaka “always clapping her leg and screaming, ‘C’mon’, before my second serve. That was a little bit disturbing.”

Earlier in the tournament, Jay Clarke complained vociferously to the umpire about fellow Brit Dan Evans taking too long between points by walking one way and then back the other. Evans responded with a knowing look up to his team in the stand that brought back memories of Cristiano Ronaldo’s wink to the Portugal bench after his winding up of Wayne Rooney in the 2006 World Cup quarterfinals had provoked the England forward into getting himself sent off.

Players look for any edge they can find, and there are countless individuals and countless methods, too many to fully enumerate here.

Moving from side to side when a player has an easy shot to distract them; repeatedly catching serve tosses; rope-a-doping players by exaggerating physical issues or grunting for longer than normal to put your opponent off their stride — Sabalenka, Siegemund’s opponent Tuesday, has been criticized for the volume and extended nature of some of her grunts. Players can be penalised for making a mid-point noise that’s deemed to be a hindrance, but again, it’s a tough thing to enforce definitively.

Siegemund, though she may not see it this way, will employ every trick she knows against Sabalenka today as she tries to bridge a rankings gap of 103 places.

(Illustration: Kelsea Petersen)