Shakespeare and Pembroke Castle (Creative Commons)

Shakespeare and Pembroke Castle (Creative Commons)

Dr Michael John Goodman

It was recently announced that the Winter Season at Shakespeare’s Globe is to include a bilingual production of Romeo and Juliet called Romeo a Juliet.

Produced by Theatr Cymru the play promises to be a production that ‘will weave together Welsh and English, exploring Welsh identity and offering a new perspective on Shakespeare’s timeless play’. Next year, Michael Sheen’s new Wales National Theatre, in a co-production with the Wales Millenium Centre, will produce a new play by Gary Owen called Owain and Henry which will examine, in blank verse, the rebellion Owain Glyndŵr, the last Welsh-born Prince of Wales, led against Henry IV in the fifteenth century.

It is a story detailed in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part I, and which, no doubt, Owain and Henry will reference, but, significantly, from a Welsh perspective.

Theatr Cymru’s bilingual production of William Shakespeare’s Romeo a Juliet, in association with Shakespeare’s Globe

Theatr Cymru’s bilingual production of William Shakespeare’s Romeo a Juliet, in association with Shakespeare’s Globe

Shakespeare and Wales is a frequently overlooked aspect to the plays. Wales and Welsh characters feature prominently throughout them, even more so than Scotland and Ireland. For Shakespeare, Wales is a land of mystery and imagination, and while the main characters from the plays who we associate as being Welsh are often broadly comic, Wales is also a place where Kings derive from.

The plays also demonstrate how important the Welsh were in the cultural mixing pot of the early modern period and in forming a sense of national unity. The boundaries between the two countries are porous, Welsh citizens happily integrate into English town life, while when the English venture into Wales they are changed in profound identity-shifting ways.

Wales is one of the central locations in Cymbeline, for example, where the country is described in a brief stage direction as ‘Wales: a mountainous country with a cave’. In the play, Wales serves much the same purpose as the forests in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It do, that is as a place where misunderstandings occur, and identities become transformed and destabilised.

Yet, Cymbeline, a mix of history play and romance, and written much later than those other two plays, presents the Welsh landscape as more primal and unforgiving than the forests of As You Like It and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It is a place where isolation is the norm and learning how to live off the land is the key to survival. It is here in this ‘mountainous country’, where King Cymbeline’s kidnapped infant sons, Guiderius and Arvirargus, were taken twenty years previously at the start of the play, and where these heirs to the throne of Britain will have learnt the skills to become effective Kings.

The Welsh port town of Milford Haven is also a significant location in Cymbeline (it is also here where Richard II lands after returning from Ireland). The town is where Innogen is told to run off to after her husband Posthumus becomes wrongly convinced she has been unfaithful.

The port did not exist in the historical time the play is set – Roman Britain – but the name would have been instantly recognisable to Shakespeare’s audience, because it was here where the exiled Henry Tudor (who was Welsh, having been born in Pembroke Castle) landed with his troops from France to fight Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485. After defeating Richard, Henry would claim the crown, become Henry VII and establish the Tudor dynasty. For Shakespeare then, in Cymbeline (a play concerned with how Britain came to be), Wales is very much a place of origins – it is a land where Kings come from.

Owain Glyndŵr

Owain Glyndŵr

Wales also features as a location in Henry IV Part I in one of the most remarkable scenes Shakespeare ever wrote. In Act III Scene I the rebels, Worcester, Mortimer, Hotspur and Owain Glendower (Glyndŵr’s name is anglicised), meet at Glendower’s castle in Wales to discuss the rebellion against Henry IV and who of the three leaders will get which parts of Britain when they are victorious. In this scene, which marks a sharp contrast to the scenes of Henry IV’s court, Wales is depicted as an ancient land of prophecies, imagination, romance, song and magic.

Embodying these characteristics is Glendower himself. He is portrayed by Shakespeare as a bilingual nobleman of great intellect, but also as a warrior and mystic, highly attuned to prophecies and superstitions. Indeed, earlier in the play Henry IV describes him as ‘great magician, damned Glendower’ and the Welsh leader does much to encourage this interpretation of himself when he says: ‘At my nativity / The front of heaven was full of fiery shapes, / Of burning cressets, and at my birth / The frame and huge foundation of the Earth / Shaked like a coward.’

Glendower also claims he can summon spirits. Even though he is only in this one scene, Glendower makes such a memorable impact that it is easy to understand the attraction for playwrights like Gary Owen. And, indeed, Shakespeare, who arguably constructed so much of the modern myth around the Welsh leader in this play.

Playwright Gary Owen

Playwright Gary Owen

As the scene develops, we are introduced to Lady Mortimer, Glendower’s daughter and Mortimer’s wife. However, as Mortimer tells us, ‘My wife can speak no English, I no Welsh’. Shakespeare does not write any Welsh dialogue when Lady Mortimer speaks, he just writes the stage direction that she ‘speaks to him in Welsh’. This is then translated by Glendower, which just further adds to his power and mystique. When Lady Mortimer says she is going to sing a song near the end of the scene, Glendower conjures up the musicians from thin air.

Mortimer is enchanted by his wife, and the language barrier – the mysterious inaccessibility to her thoughts – makes her ever more attractive to him, even though Mortimer says it angers him (this anger perhaps is a recognition of the power she has over her husband). This construction of Wales by Shakespeare is one of romance, yes, but also danger: women have the power to control their men through not only song, but the Welsh language itself.

Indeed, Mortimer never joins the rebels in the battle, presumably staying in Wales with his wife. It is revealing that Glendower comments at the end of this extraordinary scene that, having completed their business, Mortimer is ‘as slow /As hot Lord Percy is on fire to go’. Mortimer replies, sadly, with the line that concludes the scene: ‘With all my heart’.

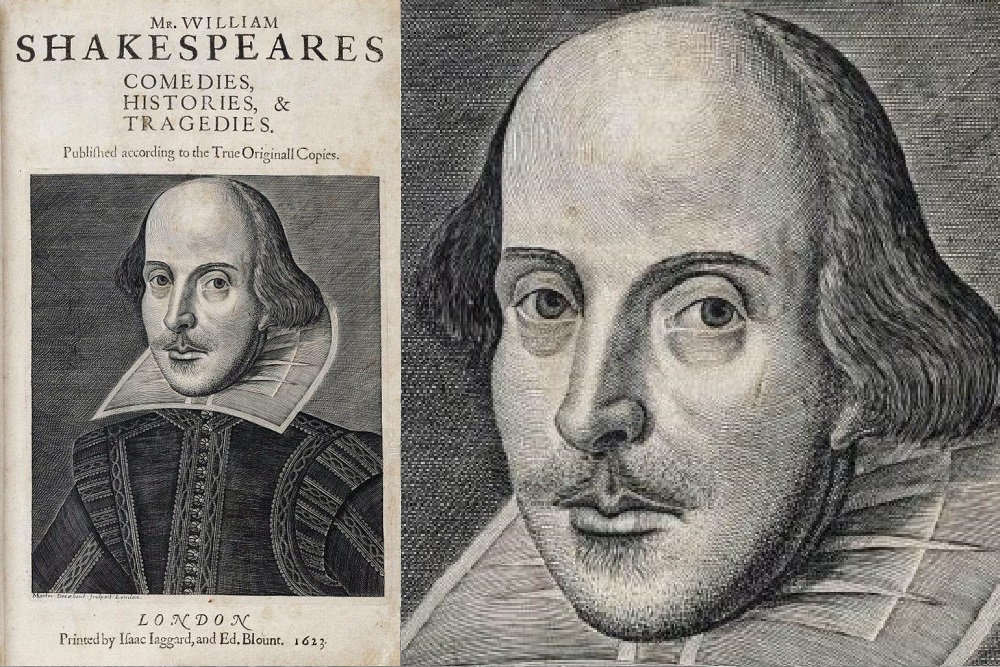

William Shakespeare – First Folio – 1623 (Public domain)

William Shakespeare – First Folio – 1623 (Public domain)

A character who does not speak Welsh in a play but is also bilingual, and whose Welsh accent causes Falstaff to claim ‘he makes fritters of English’, is schoolteacher and parson, Sir Hugh Evans, in The Merry Wives of Windsor. Sir Hugh, often thought to be based on a likely candidate for Shakespeare’s own Welsh schoolteacher, Thomas Jenkins, provides the citizens of Windsor (and us as audience members), with many moments of humour. His strong Welsh accent – his b’s are p’s, his v’s become f’s – causes all manner of various misunderstandings and allows for Shakespeare to satirise the education system he went through.

In the characteristic way Shakespeare always looks to complicate his comedies and play with language, in Act 4 scene I Sir Hugh gives the schoolboy William (surely a self-reference?) a Latin lesson. Even by the bawdy standards of some Shakespeare lines, the Latin lesson, as delivered through Sir Hugh’s Welsh accent is rude, lewd, and with Mistress Quickly listening in and increasingly misunderstanding, hilarious. ‘What is the focative case, William?’ Sir Hugh asks his student, and things quickly spiral from there.

A similar comedic Welsh character like Sir Hugh is the patriotic and devoted Captain Fluellen from Henry V. Fluellen (an anglicised version of the Welsh, Llewellyn), also has a very strong Welsh accent (b’s are replaced with p’s etc), and in one scene he compares Henry V to ‘Alexander the Pig’. The comedy here deriving both from Fluellen’s terrible attempt at flattery and getting the name of Alexander the Great wrong in the first place (sometimes Shakespeare’s jokes just do not land, admittedly). Yet, Fluellen is loyal and moral, as Henry V acknowledges: ‘Though it appear a little out of fashion / There is much care and valour in this Welshman’.

Fluellen is also responsible for one of the great images of Welsh pride on stage. When the English soldier Pistol mocks him for wearing a leek in his hat on St. David’s Day, Fluellen beats him and forces him to eat it: ‘If you can mock a leek, you can eat a leek’, he tells Pistol. Being Welsh, and expressing his Welsh identity is fundamental to Fluellen and his character.

It is Fluellen’s passion for his country that forces Henry V to acknowledge, and remind the audience, that he too is Welsh: ‘For I am Welsh, you know, good countryman’, Henry says, having been born in Monmouth Castle. This moment, coming in the final play of Shakespeare’s second group of history plays, reminds us that whilst on the surface these plays are concerned with English history, they are also, crucially, about Welsh history too. Furthermore, the line powerfully brings into focus and underscores how Welsh identity here is complex and fluid.

Daffodils, Red Dragon and Leeks (Credit: Creative Commons)

Daffodils, Red Dragon and Leeks (Credit: Creative Commons)

Outside of the plays, the relationship between Shakespeare and Wales is a living breathing one, which also has its own history, stories, people and places. We can think of all the numerous Welsh actors who have played roles in the plays, from Shakespeare’s own company to the present day, the fact that Alys Griffin, Shakespeare’s maternal grandmother, is thought to be Welsh, or that the dedicatees of the First Folio are William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, and Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery. There is even a location close to Crickhowell in South Wales, called the Clydach Gorge, where Shakespeare was apparently inspired to write A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But, as Parson Hugh Evans might say about that, ‘this is lunatics! this is mad as a mad dog!’

Dr Michael John Goodman is a freelance researcher and educator. He received his PHD in English Literature from Cardiff University and his work focuses on making Victorian illustration accessible and interesting to new audiences. He has published widely in academic journals and books, and his projects have featured in The Washington Post, The Guardian and the BBC. He is the creator of the open access resources, The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive and The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery, and has appeared on the Radio Wales Arts show discussing the relationship between Shakespeare and Wales

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.