NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

Share

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1031710/the-architecture-of-rewilding-designing-for-ecosystem-recovery

As climate instability reshapes design priorities, architecture is increasingly drawn into ecological debates not as a spectator but as a participant. Among the concepts gaining traction is rewilding, a practice rooted in the restoration of self-sustaining ecosystems through the reintroduction of biodiversity, the removal of barriers, and the rebalancing of human presence in the landscape. Though often associated with conservation biology, rewilding also opens up new spatial and architectural imaginaries — ones that challenge conventional notions of permanence, authorship, and use.

Traditionally, architecture has been seen as an agent of ecological disruption — constructing over wetlands, fragmenting habitats, and redirecting waterways. But a growing number of projects and practices are beginning to invert that logic. They ask: What if architecture could catalyze rewilding, rather than being an obstacle? What if built form could scaffold ecological regeneration, enabling the return of species, the healing of soil, or the resynchronization of hydrological cycles?

This shift implies designing not for stability but for transformation. It reframes architecture not as an imposition on the land but as a frame, a mediator, or even a temporary caretaker. As argued by Keller Easterling in Extrastatecraft, spatial systems can “tune” environments rather than “control” them. This tuning becomes critical when designing for ecosystems in flux.

Related Article Rewilding in Architecture: Concepts, Applications, and Examples Typologies for Rewilded Grounds Wildlife crossing, A1, Israel. Image © Hagai Agmon-Snir via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 4.0

Wildlife crossing, A1, Israel. Image © Hagai Agmon-Snir via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 4.0

In architectural discourse, rewilding refers not merely to the ecological act of restoring biodiversity or removing human intervention but to a broader design approach that challenges dominant paradigms of control, permanence, and linear development. It implies a reconfiguration of how we build toward strategies that are adaptive, reversible, and embedded in ecological processes. In this sense, it is less about creating new objects and more about negotiating presence, allowing landscapes to regenerate while enabling careful and temporary forms of access or inhabitation.

Banff National Park, Canada. Image © m01229 via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 2.0

Banff National Park, Canada. Image © m01229 via Wikipedia under CC BY-SA 2.0

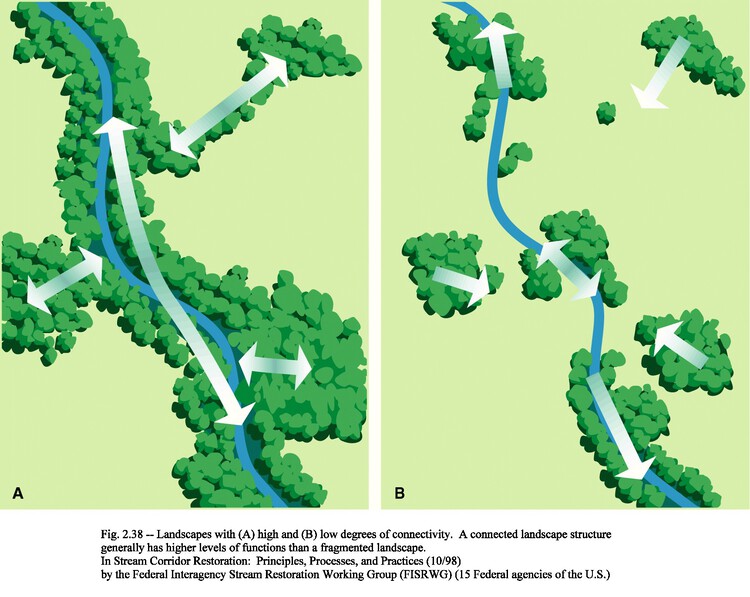

One of the most visible spatial expressions of this logic can be found in wildlife corridors — bridging infrastructures designed to reconnect fragmented ecosystems. These structures often serve to mitigate the damage caused by road networks, railways, and other barriers imposed by human mobility. In Canada’s Banff National Park, for example, a network of overpasses and underpasses has been developed in coordination with ecologists and wildlife biologists. But while these interventions are often celebrated for their ecological impact, it is crucial to recognize that they do not solve the problem of fragmentation — they merely attempt to repair a condition that human infrastructure has created in the first place.

Scape Landscape Architecture’s Living Breakwaters project off Staten Island explores the intersection between ecological resilience and infrastructural performance. Developed in response to Hurricane Sandy, the project installed a chain of submerged and semi-emergent breakwaters designed to reduce coastal erosion and wave energy while fostering marine biodiversity. The structures serve as substrates for oyster reef growth, water filtration, and fish habitat, turning coastal defense into a multi-layered ecological system. The intervention is not symbolic: monitoring studies have documented increased species richness and sediment stabilization. Here, architecture becomes a dynamic interface, mediating natural processes and urban vulnerability.

© Brittney Le Blanc, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

© Brittney Le Blanc, via Flickr under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The vocabulary of rewilding often draws on vernacular typologies reimagined for new ecological roles. But instead of monumental gestures, we encounter discreet, often fragmentary structures that facilitate observation, immersion, and cohabitation without asserting dominance. These typologies echo familiar forms but are reconfigured to accommodate new modes of ecological negotiation. Their aim is not to occupy space, but to frame it, offering minimal, often reversible interventions that seek to make ecological processes legible rather than controlled.

TIRPITZ / BIG. Image © Mike Bink

TIRPITZ / BIG. Image © Mike Bink TIRPITZ / BIG. Image © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

TIRPITZ / BIG. Image © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

In the Tirpitz Museum from BIG, the architectural gesture is one of subtraction. The museum is not constructed on the terrain but within it, carefully hollowed into the sand to preserve the continuity of the ecosystem. Circulation paths are traced with surgical precision, and the building is rendered almost invisible from a distance. This apparent lightness, however, invites scrutiny: to what extent does the disappearance of architecture equate to its ecological responsibility? While the project minimizes visual impact, it still requires excavation, stabilization, and material interventions within a fragile coastal environment. The value lies not in its invisibility per se, but in its attempt to recalibrate the relationship between building and ground, from assertion to accommodation.

EarthSea Pavilion / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

EarthSea Pavilion / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

This gesture of negotiation becomes more open and participatory in the work of Studio Ossidiana, a practice whose architectural language invites encounters between humans and other species. In the Earthsea Pavilion, installed in the courtyard of Hof Bladelin during the 2024 Bruges Triennial, architecture is conceived as a living organism — a contemporary chimera composed of minerals, plants, animals, organic matter, fungi, and bacteria. The pavilion consists of a six-meter-wide cylindrical structure made of layered materials — earth, peat, shells, and leaves — stacked like geological strata. It changes over time, integrating seeds that sprout, decomposing into fertile soil, and becoming a sanctuary for birds, bees, and walkers. More than a pavilion, it is a soil-making machine — a porous, multispecies shelter that filters water, absorbs weather, and grows through succession.

The Seeds’Garden / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana

The Seeds’Garden / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana The Seeds’Garden / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana

The Seeds’Garden / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana

This approach resonates with The Seeds Garden, a circular installation presented at the Shenzhen Architecture Biennale, where compressed soils, seeds, and minerals formed a walkable landscape that gradually transformed over time. Designed as an evolving surface, the garden blurred the lines between architecture and ecology, becoming both a space for public interaction and a fertile ground for botanical imagination.

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

At the NDSM Lusthof, the studio revisits the historical typology of the ‘lusthof’— a sensory garden once reserved for the elite — and reimagines it as a partially enclosed, multispecies observatory in the heart of a former shipyard. The project combines a circular architectural fence with peepholes, cast concrete platforms, and medicinal planting inspired by Ottoman gardens. It questions who has access to green space in contemporary cities and how gardens can act as inclusive infrastructures for public gathering, ecological experimentation, and cultural memory. Even their Platform for Humans and Birds, a floating architectural element, demonstrates how gentle spatial devices can facilitate shared use. The platforms function as a garden, rest, or stage — blurring categories and resisting typological definition.

Are these devices truly facilitating ecological regeneration, or are they merely aestheticizing our guilt? How can we ensure that such interventions are not designed to ease our conscience, but to meaningfully reorient how we inhabit the land? The challenge is not to build less, but to build critically, to design as if architecture were part of a living system, rather than a gesture imposed upon it.

Together, these projects articulate a voice within rewilding architecture — one that remains lightly present and open to other species. They raise a crucial question: Are these devices truly facilitating regeneration, or aestheticizing our guilt? The challenge is not to build less, but to build critically — to design as if architecture were part of a living system.

From Form to Process Puentes de rai╠üces vivientes – Pueblo Khasis (India). Image © Peter Oxford

Puentes de rai╠üces vivientes – Pueblo Khasis (India). Image © Peter Oxford

The architecture of rewilding does not begin with the pursuit of form, but with the recognition of ecological process. It favors tools over icons, conditions over compositions, and interventions that are open-ended, reversible, and adaptive. Rather than enclosures or monuments, it privileges devices — spatial supports that make ecosystems perceptible without seeking to stabilize them.

Newbern Town Hall, Auburn University / Rural Studio. Image © Timothy Hursley

Newbern Town Hall, Auburn University / Rural Studio. Image © Timothy Hursley

This is often accompanied by a material ethic grounded in low-impact construction. Projects tend to use local, regenerative, or biodegradable materials and employ dry joints or demountable systems that allow for dismantling, reuse, or decomposition. The work of Rural Studio exemplifies this logic. Originally framed around social housing and education, the studio’s design embraces circularity, constructing with salvaged or locally available materials, often in ways that allow buildings to weather and adapt in situ.

Represas de pesca – Pueblo Enawenê-nawê de Mato Grosso (Brasil). Image © Deep Forest Foundation

Represas de pesca – Pueblo Enawenê-nawê de Mato Grosso (Brasil). Image © Deep Forest Foundation

At a conceptual level, Gilles Clément’s idea of the Third Landscape offers a critical framework for rethinking where and how we build. Described as “the sum of the spaces left over by man to landscape evolution”, the Third Landscape includes abandoned lots, road verges, and post-industrial edges. Designing in these contexts means adopting a logic of humility: understanding that architecture may be tolerated by the ecosystem, but is rarely necessary. The challenge is to resist the compulsion to define, and instead design to accommodate what is already becoming.

Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0 Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

Knepp Estate Rewilding, West Sussex. Image © Mark Wordy via Flickr under CC BY 2.0

This ethic is present in the Knepp Estate, one of the most well-known rewilding initiatives in Europe. While not designed by architects, the estate’s sparse visitor infrastructure — elevated walkways, compost toilets, timber platforms — illustrates how built form can support ecological recovery without imposing upon it. They are designed to retreat into the background, degrade naturally, or be removed entirely as the landscape evolves. In this way, they exemplify an architecture that does not seek permanence, but relevance across different temporal scales.

Designing from form to process implies a fundamental displacement of the architect’s centrality, aligning architecture with ecological processes that grow beyond the building itself.

Ecology, Obsolescence, and Succession Riparian Buffers as Wildlife Corridors. Image © placeuvm via Flickr under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Riparian Buffers as Wildlife Corridors. Image © placeuvm via Flickr under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While most buildings are conceived within a framework of design, delivery, and occupation, ecological recovery follows slower, more unpredictable rhythms — measured not in weeks or years, but in cycles of succession, decay, and return. In these contexts, architecture must be reconceived not as a fixed endpoint, but as a participant in ongoing ecological processes, subject to weathering, transformation, and obsolescence.

Islas flotantes de AI-Tahla – Pueblo Ma’dan (Irak). Image © Jassim Alasadi

Islas flotantes de AI-Tahla – Pueblo Ma’dan (Irak). Image © Jassim Alasadi

This requires a shift in how we think about authorship and permanence. As Keller Easterling proposes, spatial systems should be valued not for what they are, but for their disposition — their capacity to shape behaviors, accommodate change, and activate conditions for something else to emerge. A boardwalk that gradually becomes a habitat, or a pavilion overtaken by moss and insects, may be more successful than one that remains unchanged. The success lies not in its durability, but in its capacity to disappear with purpose.

Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher

Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher

Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher

This is reflected, albeit subtly, in the Life House by John Pawson. Though not a rewilding project in the strict sense, the building embraces temporal awareness in its most essential form: silence, stillness, and retreat. In its refusal to dominate the landscape or define a fixed use, it fosters not only the regeneration of place, but of perception — a quiet alignment with the temporalities of the non-human world.

Wooden Chapel / John Pawson. Image © Felix Friedmann

Wooden Chapel / John Pawson. Image © Felix Friedmann

Designing for rewilding necessitates transcending disciplinary boundaries to collaborate with ecologists, hydrologists, soil scientists, indigenous custodians, and local communities. These actors carry forms of knowledge that often fall outside architectural training but are crucial for understanding the complexity of regenerating land.

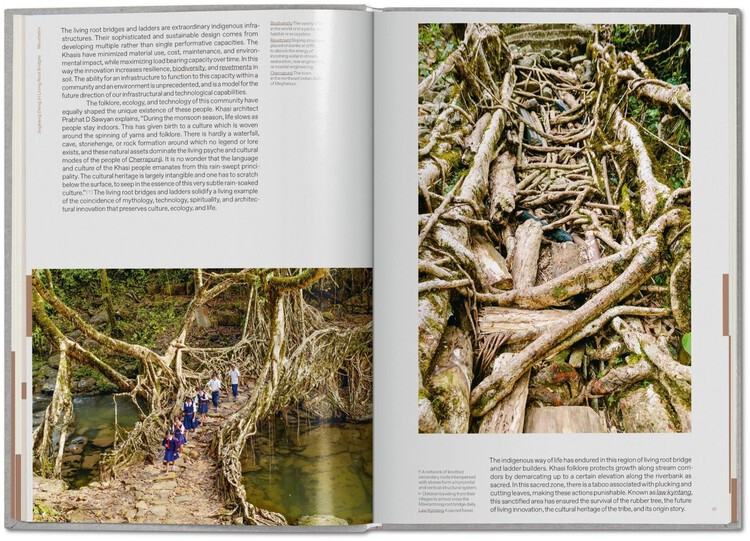

Puentes de raíces vivientes – Pueblo Khasis (India). Image Courtesy of Julia Watson

Puentes de raíces vivientes – Pueblo Khasis (India). Image Courtesy of Julia Watson

As Julia Watson argues in Lo–TEK: Design by Radical Indigenism, traditional ecological knowledge offers long-tested models for coexisting with ecosystems through adaptive, cyclical, and place-specific practices. These systems negotiate with nature through seasonal rhythms, constructed wetlands, and spiritual relationships to territory. Watson’s work advocates for design that is not representational or extractive, but co-evolutionary: shifting from control to care, and from monumentality to relational infrastructure.

Islas flotantes de AI-Tahla – Pueblo Ma’dan (Irak). Image © Agata Skowronek

Islas flotantes de AI-Tahla – Pueblo Ma’dan (Irak). Image © Agata Skowronek

This relational stance carries clear spatial consequences. It implies architectural practices that are less about form-making and more about facilitating ecological and social processes. It requires protocols that respect the histories and meanings of land, particularly in post-extractive, colonized, or marginalized rural territories. In some cases, this involves participatory cartographies and co-design processes that integrate local knowledge. In others, it means recognizing the legitimacy of land back movements or community-led stewardship, where the architect’s role is not to design for, but to enable designing with.

Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher

Life House / John Pawson. Image © Gilbert McCarragher

Academic institutions are also beginning to respond to these shifts. At the Oslo School of Architecture and Design, research into design by subtraction explores how removing infrastructure can be an act of design in itself. Meanwhile, the Landscape Architecture Department at ETH Zurich is developing predictive tools for ecosystem behavior, integrating models of plant succession, water cycles, and climate scenarios into early design phases. Both methods challenge the architect to think in time and not only about form.

This temporal and collaborative sensitivity resonates with Anna Tsing’s idea of the “arts of noticing” — a practice of attending to what is already happening on the ground, even in degraded or overlooked landscapes. Design becomes less about proposing new futures and more about amplifying latent potentials already present.

Architecture After the Anthropocentric Project

The architecture of rewilding emerges not as a stylistic response but as a disciplinary repositioning of the ecological and ethical challenges of the Anthropocene. In a time marked by planetary instability, habitat fragmentation, and irreversible loss, rewilding reframes design as a form of environmental responsibility rather than expression. It questions the very foundations on which modern architecture has been built: extraction, control, growth, permanence.

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

NDSM Lusthof / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

In this context, architecture is asked not to represent nature, but to participate in its recovery. This involves designing for processes that exceed human timescales, anticipating succession, decomposition, and return. It demands frameworks that allow life to adapt, thrive, and reconfigure space over time. Rather than foregrounding form or authorship, the architecture of rewilding invites a practice rooted in care, impermanence, and situated knowledge. It is less concerned with building objects than with enabling conditions — supporting soils to regenerate, water to circulate, species to return.

To build within the Anthropocene is to accept that architecture alone cannot solve ecological collapse, but it can choose to stop contributing to it. It can align itself with the logic of recovery, positioning itself not as an endpoint but as an opening. In doing so, rewilding expands the discipline’s remit: from shaping buildings to shaping the possibility of life beyond them.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Regenerative Design & Rural Ecologies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.

‘Living Breakwaters’ by SCAPE Landscape Architecture Wins the 2023 Obel Award. Image Courtesy of SCAPE

‘Living Breakwaters’ by SCAPE Landscape Architecture Wins the 2023 Obel Award. Image Courtesy of SCAPE Platform for Humans and Birds / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi

Platform for Humans and Birds / Studio Ossidiana. Image Courtesy of Studio Ossidiana, Riccardo de Vecchi