The 1980s was fearful point in our history when it came to nuclear conflict Rishworth Moor, Saddleworth, Oldham. A communications tower built in case of nuclear attack has stood above the M62 motorway for nearly 60 years(Image: Phil Taylor)

Rishworth Moor, Saddleworth, Oldham. A communications tower built in case of nuclear attack has stood above the M62 motorway for nearly 60 years(Image: Phil Taylor)

War in Ukraine and Israeli and US attacks on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure has seen global tensions skyrocket as the world feels like a more volatile place than ever.

Fears Vladimir Putin’s military campaign in Ukraine could spread to other European nations has seen the UK and other NATO members commit to spending more on defence in preparation for a possible attack in the near future.

Earlier this month, Keir Starmer warned the UK faces a “moment of danger and threat“, and said Putin’s aggression must not go unchallenged as he unveiled a long-awaited plan to put the country on a war footing. Days ago, the PM said Europe has ramped up its focus on security in the face of new threats, with the UK vowing to spend 5% of its GDP on national security by 2035

The UK government will also see the “biggest strengthening” of its UK nuclear capabilities in 30 years, confirming the RAF will get at least 12 F-35 stealth jets capable carrying nuclear warheads. With all this in the news, it’s no wonder that both the search terms “nuclear war” and “world war 3” have spiked in the UK over the last week, according to Google Trends.

With the harrowing scenes we see dominating the news on TV, it’s easy to see how anxiety around such a potential threat would increase. It’s worth noting there have been times in 20th century when nuclear conflict seemed a much more immediate threat.

Previously, the national and local government – including Greater Manchester – have issued their own advice and plans on likely scenarios regarding a potential nuclear threat.

The Cold War

In the late 1940s, Eastern European nations became satellites of the Soviet Union – including East Germany, Poland, Hungary, the former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Romania. The response from the US and the West was the creation of NATO in 1949.

In 1961, the Soviets installed the Berlin Wall which became a symbol of the Cold War. From the 1950s through to the late 1980s, the spectre of nuclear war between the West and the Soviet Union loomed over Europe and the rest of the globe.

Many experts believe that the Cuban Missile Crisis of the 1960s was the closest the world ever came to spiralling into nuclear conflict.

The arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, along with their respective allies during the Cold War, only escalated geopolitical tensions and public fear. This did not cease until 1991 when the power and influence of the Soviet Union waned and its Communist regime collapsed

For younger readers, it’s difficult to truly comprehend the fears surrounding nuclear war that people experienced even in the 1980s. There were public information broadcasts on what to do in the event of an attack; even children growing up in that decade were aware of the frightening discussions around the possibility of nuclear war.

Manchester’s own piece of Cold War history survives in the form of the Guardian telephone exchange. Also known as ‘Scheme 567’, this clandestine network of tunnels and a bunker still survives some 35 metres beneath Manchester’s streets and edifices.

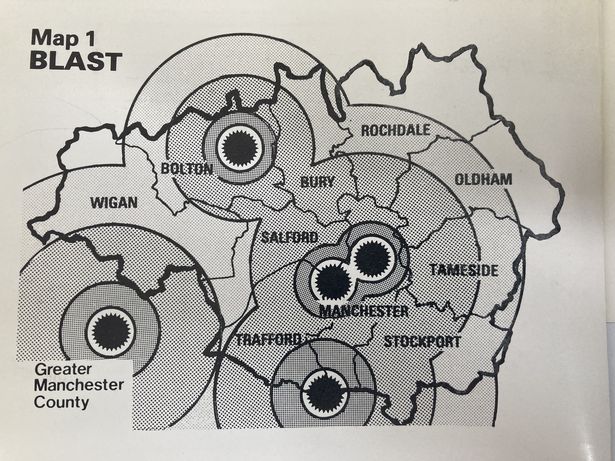

A nuclear attack on Manchester Image of a potential attack from the 1983 booklet Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester

Image of a potential attack from the 1983 booklet Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester

“If a one megaton bomb exploded in the air about 8,000 feet above the centre of Manchester it would completely destroy the city centre and would do severe blast damage as far away as Stockport, Ashton, Worsley and Hale,” the authors of Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester wrote.

“At least 300,000 people (about 11% of Greater Manchester’s population) would be instantly killed by blast effects, and perhaps twice that number would be seriously injured. The risk of injury from flying glass and other debris would extend for about 12 miles (e.g. to Wilmslow, Marple Bridge, Stalybridge, Rochdale, Bolton, Tyldesley and Lymm.)”

Anyone caught out in the open when the blast occurred, which could perhaps be up to 200,000 people, would receive third degree burns – ‘even as far as Swinton, Stretford, Withington, Audenshaw, Failsworth and Prestwich‘. Thousands more would be blinded.

And that was the best case scenario. More likely Manchester would be hit several nukes at once. In 1982 the organisation Scientists Against Nuclear Arms, looked at the effects of seven one-megaton bombs dropped on the airport, Burtonwood airbase, Beswick, Old Trafford and Bolton.

If that happened about 1.4 million people would be killed or seriously injured, and about 1 million would be affected by radiation, most of whom would die within two months. “In total 2.6 million of Greater Manchester’s 2.8 million people would die within two months of such an attack,” SANA claimed.

Front cover of the 1983 booklet Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester

Front cover of the 1983 booklet Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester

But this wasn’t scaremongering for scaremongering’s sake. The pamphlet’s apocalyptic tone was entirely deliberate.

Three years earlier, on November 5, 1980 Manchester became the world’s nuclear free city – placing itself at the forefront of the campaign to ban atomic weapons. The city council called upon the government to ‘refrain from the manufacture or position of any nuclear weapons of any kind within the boundaries of our city’ – and urged local authorities throughout Great Britain to do the same.

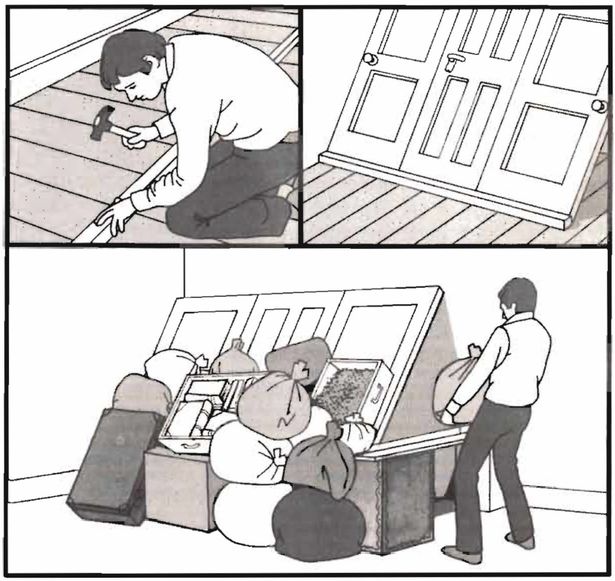

Around the same time the Conservative government produced its infamous 1980 booklet Protect and Survive, advising the public on how prepare for a nuclear attack. The source of a many a childhood nightmare, it gave guidance on how to construct a fallout shelter under the stairs or kitchen table using sandbags and bits of furniture and urged people to whitewash their windows to reflect the heat flash.

Image from the 1980 UK government pamphlet Protect and Survive, which advised the public what to do in the event of a nuclear attack

Image from the 1980 UK government pamphlet Protect and Survive, which advised the public what to do in the event of a nuclear attack

But the Labour-controlled Labour Greater Manchester Council believed that was pointless, and could in fact encourage the idea that nuclear war ‘might not be so bad’. Talk of ‘civil defence’ was a ‘cruel confidence trick’, the GMC believed, so published their own booklet, Emergency Planning and Nuclear War in Greater Manchester, which set out the opposing school of thought.

Declaring Manchester a ‘nuclear-free zone’ was a world first, but by the end of 1982, 150 local authorities had joined Manchester in opposing the arms race. And it had an impact.

That year, the government wanted to stage a National Civil Defence exercise to show its stomach for nuclear war. But the Nuclear Free local governments refused to take part, and to date no such rehearsal exercise has ever taken place.

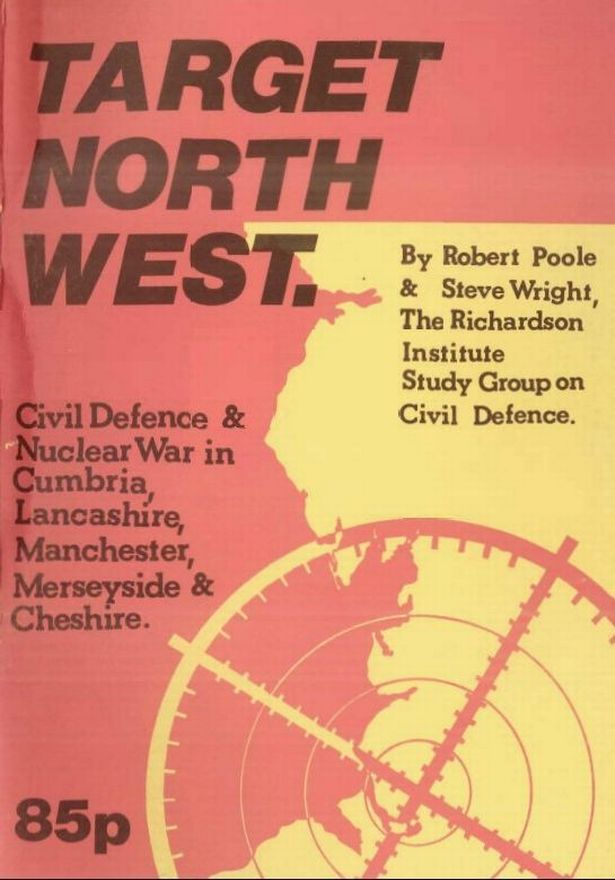

Target North West Cover of Target North West. The first independent scholarly institute to conduct research into how a nuclear attack would affect the North West of England

Cover of Target North West. The first independent scholarly institute to conduct research into how a nuclear attack would affect the North West of England

Defence strategies were also proposed for how the UK and its major cities might respond in the event of an attack. One document, ‘Target North West‘ produced by the Richardson Institute for Peace and Conflict Research, was the first independent scholarly institute to conduct research into how a nuclear attack would affect the North West of England.

A copy of the report is available at the Wilson Centre, an online digital archive that publishes now declassified documents. It contains fascinating information about how large cities might respond in the event of a nuclear attack. Greater Manchester and Merseyside were both seen as likely targets because of their “urban-industrial significance.”

Despite the obvious devastation a nuclear attack would inflict on any country the researchers, in consultation with a regional government emergency planning officer at the time, outlined a plan for civil defence to ensure “our survival and recovery to some semblance of normality after attack.”

A large scale Civil Defence exercise held at Portsmouth. Taking part were 1,400 soldiers, a Naval radio activity monitoring team, as well as men and women of the Civil Defence. February 28, 1951

A large scale Civil Defence exercise held at Portsmouth. Taking part were 1,400 soldiers, a Naval radio activity monitoring team, as well as men and women of the Civil Defence. February 28, 1951

Following a nuclear conflict, plans were in place to replace the central government with a system of localised government composed of 12 regions. Merseyside, Lancashire, Cumbria, Manchester and Cheshire would compromise one of the regions. The Regional Seat of Government would be constructed within the Regional Armed Forces HQ at Fulwood Barracks, Preston, which would have overall control.

For Manchester, Merseyside, and Cheshire, the old air defence radar station concrete bunker at Hack Green, near Nantwich, was reportedly being “secretively and extensively refurbished” as another base of operations.

The report also states that during the “pre-attack period of uncertainty,” the UK government had already decided to broadcast any imminent nuclear launch to the public as a means of readying the population. A wartime broadcasting service would disseminate information to help keep the public calm and include shelter-building instructions.

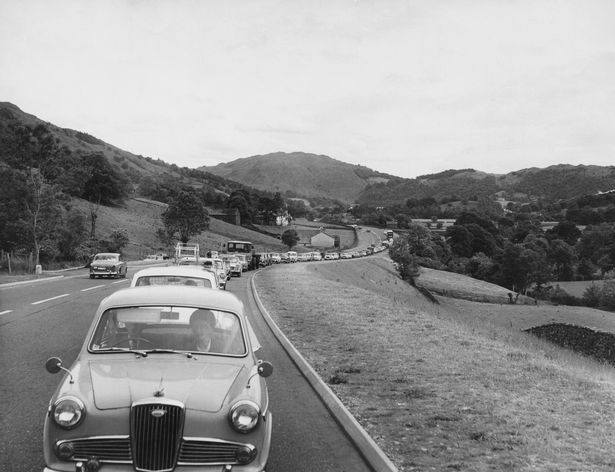

Congested traffic on the Keswick Road in Cumbria, circa 1970. Cumbria is said to be one of the rural destinations people from Manchester would flee to in the event of a nuclear war

Congested traffic on the Keswick Road in Cumbria, circa 1970. Cumbria is said to be one of the rural destinations people from Manchester would flee to in the event of a nuclear war

It was predicted that a large number of people from Manchester and Merseyside would ignore the advice to stay home and attempt to flee to the more rural areas of the North West, like Cumbria, only to discover roads closed off for essential military use.

The plan states: “The crowds will be turned back to the prime target zones like rats in a trap. Ugly disturbances are certain to develop in some areas as the full implications sink in. But as the last section made clear, the police are already making plans for such an eventuality to move in with sophisticated riot technologies to reassure the public.”

Public health, food distribution and ‘burial of the dead’

Among the creation of regional government posts following an attack, there would be district food and food distributions officers, a scientific adviser, communications officer and other roles to direct health, sanitation and, rather grimly, an officer responsible for the ‘burial of the dead’. The report even cites the importance of requisitioning the school meal service for emergency feeding of the surviving population.

Members of the Civil Defence training to create an improvise field kitchen where they can prepare food for survivors of a suppose nuclear explosion. December 8, 1965

Members of the Civil Defence training to create an improvise field kitchen where they can prepare food for survivors of a suppose nuclear explosion. December 8, 1965

The distribution of food would also be under the control of local government, something the plan suggests would come into place within two weeks of a nuclear attack. The report states: “The current aim is to provide 20 million people in Britain with ‘half a pint of stew-type meal’ a day, cooked with burning rubbish; Cumbria hopes to add a cup of tea a day. The government reportedly estimates that people could survive on this sort of diet for two years.”

What is the likelihood of nuclear war? British Royal Air Force personnel wait in a bunker wearing full Nuclear Biological and Chemical suits after a warning of a Scud missile attack on their base in Kuwait

British Royal Air Force personnel wait in a bunker wearing full Nuclear Biological and Chemical suits after a warning of a Scud missile attack on their base in Kuwait

Recently the Doomsday Clock was moved to 89 seconds (one minutes, 29 seconds) to midnight, the closest it has been set to midnight since its inception in 1947.

Determined by the non-profit organisation Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Doomsday Clock is a symbol that represents the estimated likelihood of a human-made global catastrophe. The clock is seen more as a metaphor, and not a prediction, for the threats to humanity. These include nuclear threats, climate change, bioterrorism, and artificial intelligence.

Despite this, many experts believe the overall probability of a full-scale nuclear war is still relatively low, with many believing climate change presents a bigger threat to humanity. Phew.

However, recent conflicts, and the continued proliferation by the major nuclear powers, US and Russian (and increasingly China) in the number of warheads they possess, continues to raise concerns about the potential for escalation.

Looking back at the nuclear tensions of the 1980s, it’s with more of a sense of fascination as to how emergency plans could have been implemented 40-years ago. Back then, they could never have predicted today’s advanced technologies such as the internet, the shifts in global politics, and the increasing rise of private industry supplying many of the solutions in a modern world.

The Manchester Evening News has contacted Manchester Council, asking if there are plans in place for Manchester in the event of a possible nuclear attack.

Join the Manchester Evening News WhatsApp group HERE