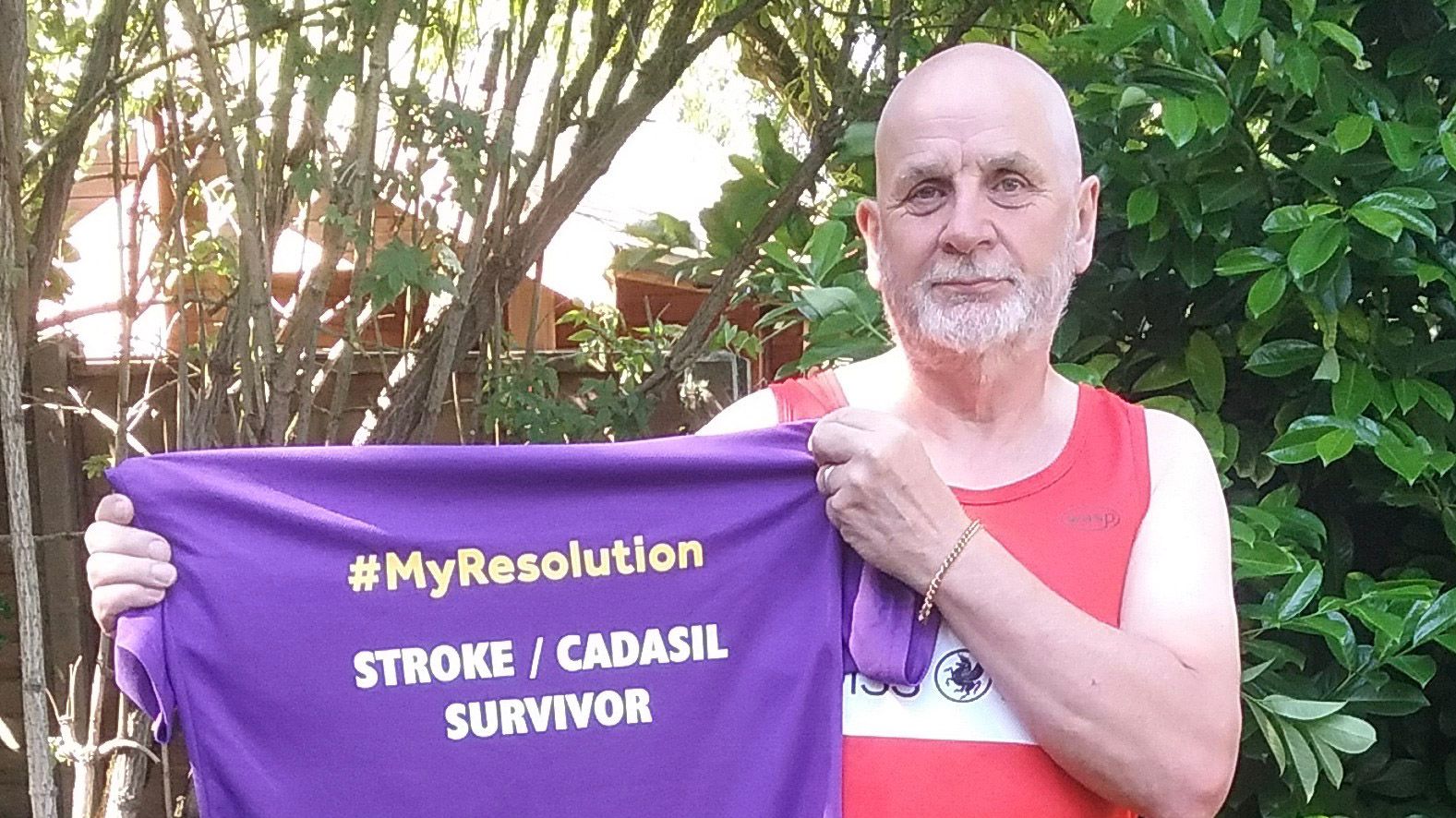

Glenn Bate was diagnosed with CADASIL after suffering a stroke in 2015

Glenn Bate has run races and raised awareness of Cadasil since he was diagnosed in 2015Author: Dan MasonPublished 6 minutes ago

A man living with a rare genetic condition has said getting help from a Cambridge clinic has changed his outlook on life.

Glenn Bate was diagnosed with CADASIL (Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy) in 2015 after a stroke.

The diagnosis came as a surprise to Glenn, 69, as the condition is not widely known about and because he was adopted, doesn’t know any relatives with the condition.

“When I first left hospital I had problems with walking, balance and anxiety, it felt like I was going home to die,” Glenn said.

“Having a stroke changed everything in my life, like I had to relearn everything; I couldn’t drive, and I felt my life was over.”

What is CADASIL?

CADASIL – thought to affect several thousand people in the UK – is an inherited vascular disease caused by a faulty gene.

It affects small blood vessels throughout the body increasing the risk of bleeds and this effect goes largely unnoticed except where it causes bleeding in the brain leading to stroke.

People with CADASIL may experience multiple strokes which can start between the ages of 30 and 60 with many of these minor and patients often recover.

There is currently no cure for CADASIL and the overall effect can be debilitating, with many patients experiencing migraines and can go on to develop dementia.

Figures from the Alzheimer’s Society show around 2 in 3 people who have CADASIL will develop dementia at some point in their lives.

Between 1 in 50,000 and 1 in 25,000 people are diagnosed with CADASIL, although genomic studies suggest many more people could be undiagnosed.

‘I’m not dying today, I’m living today’

Glenn – from Diss in Norfolk – was referred to the CADASIL clinic at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, which also supports the mental health of patients following a stroke and diagnosis with CADASIL.

After his stroke, Glenn went on to run several 5k and 10k races and completed the Yorkshire Three Peaks Challenge to raise funds for CADASIL Support UK.

When he returned to work, Glenn recalled a conversation he had, one that helped change his life.

“We got left alone at dinner time going through the results and he said ‘why are you busy dying? Don’t forget to live’ and that changed my life,” Glenn said.

“I thought ‘I’m not dying today, I’m living today’.

“I think the main thing is always to keep myself busy and hopefully that will stop any decline; there are good and bad days, but on the whole, I have a fantastic life.”

The study

A recent study into CADASIL was led by Professor Hugh Markus, a consultant neurologist at Addenbrooke’s and Professor of Stroke Medicine at the University of Cambridge.

In it, 555 people were referred to the clinic between 2001 and 2023 and during that time, awareness and understanding of the condition as well as access to specialist care have all improved.

On average, patients referred to the clinic before 2016 experienced their first stroke between the ages of 37 and 56.

While patients referred since 2016 typically didn’t start getting strokes until almost five years later, between ages 42 and 61.

“CADASIL is very rare but in most cases, there will be a family history of the disease; you may have parents or grandparents who had strokes at a younger age and often, the migraine attacks can be prolonged,” Professor Markus said.

“We’ve seen over 500 people with the disease, so we’ve gained a lot of experience on how to manage it, not only the physical side but the psychological side and how you cope with this difficult diagnosis.”

Professor Hugh Markus said the study is having a “positive impact” on improving awareness around CADASIL

The CADASIL clinic provides genetic testing to diagnose patients and screen family members, which aims to help more people understand the condition and offer targeted advice for patients on how to reduce their stroke risk.

Professor Markus – who works closely with families in the UK affected by CADASIL – believes the progress made through the study is positive, but more work is needed to help more patients.

“CADASIL is a leading genetic cause of early-onset strokes and has a huge impact on families,” he added.

“It means a lot to see that the work we are doing to improve awareness and diagnosis appears to be having a positive impact; there is still a lot more to do as we still have limited options for treating this condition.

“There are such advances in genetic technologies and gene therapies that there may well be a therapy for CADASIL before too long.”