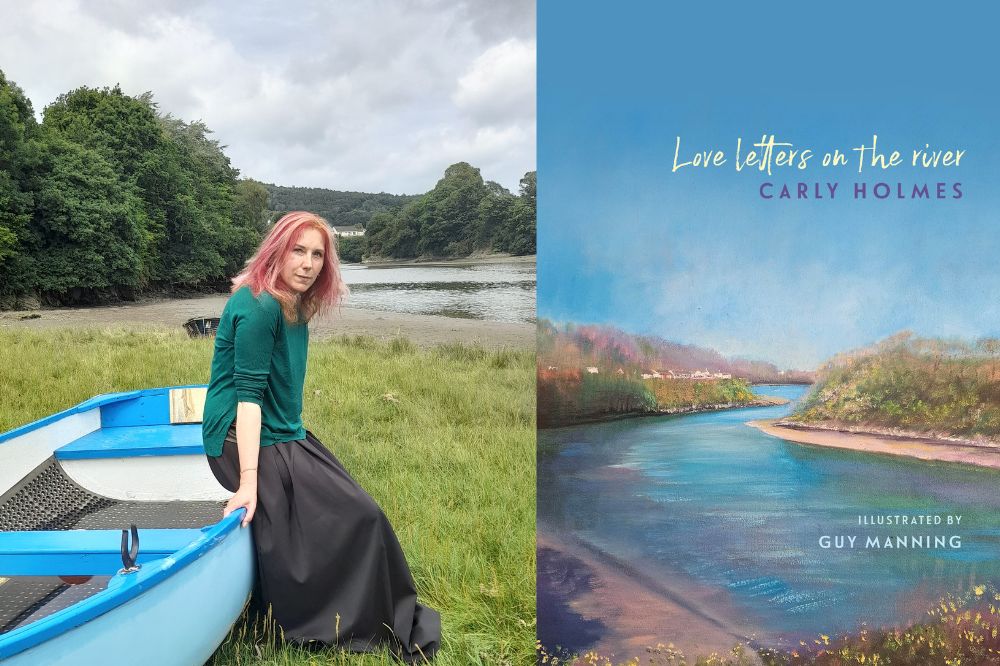

Love Letters on the River by Carly Holmes

Love Letters on the River by Carly Holmes

Carly Holmes

If my future self had told ten-year-old me, or even twenty-year-old me, that I would one day be a published writer – my life’s dream since I learned to read – I would have been ecstatic. If my future self had mentioned that I would one day be a writer of non-fiction, I would have been confused; would probably have queried whether they’d mistaken me for another Carly. Because this one writes stories. She takes a kernel of truth and then wraps layers of fiction around it.

I would never have attempted to write a collection of nature essays if I hadn’t been asked to. I don’t think I’d have ever considered it. What does a non-expert like me have to offer to a genre that is already vast and maybe even a little overstuffed? For the last decade or so, and particularly since the pandemic, “Being in Nature” has become a thing. Nature as healer, as entertainer, as server. Why merely swim in the sea when you can “wild” swim, and why camp when you can pitch your tent somewhere other than a campsite and “wild” camp?

As I say in the foreword to my essay collection Love Letters on the River, I greet the natural world around me from a place of simple wonder and love. I have no specialised advice to offer readers, and I have no hook to hang this book on. No bereavement, no relationship breakdown: nothing that nature saved me from.

Vicarious satisfaction

Except, from as far back as I can remember, every day of my life I’ve had at least one moment where, for example, the sight of a hungry blackbird pulling a fat worm from the earth – that feeling of vicarious satisfaction at the thought of a full stomach – or the sound of a raven flying overhead, has lifted me from the (often petty) preoccupations of my own life and anxieties.

I was lucky enough to grow up in a household with lots of pets. We moved to Pontsian in Ceredigion (Dyfed, back then) when I was eleven, and my parents added geese, ducks and chickens to the usual domestic assortment of cats and dogs. They were all part of our extended animal family and I probably spent more time with these non-human companions than I did with other humans. I’d sit in my bedroom with my cat Sootica and watch her for hours as she groomed herself and groomed me and then curled into my arms for a nap. I’d marvel at the sheer weirdness of the fact that this creature – whose language I couldn’t speak and whose rituals and behaviours were a mystery – chose to live her life alongside me. Loving me as purely and wholly as I loved her. It still blows my mind, in the best possible way, to think that I share the happiest and most special parts of my life with fellow animals who aren’t human.

I’m not a “birder”. I don’t feel any sense of triumph or satisfaction from adding a tick to my list of rare bird sightings. I don’t have a list. Yesterday there was a greenfinch on the feeder in the garden. The first I’ve seen in years, since trichomonosis tore through their population around here and effectively decimated them. (It did the same to the chaffinches a couple of years ago, and then the bullfinches earlier this year.) I watched as the stout, olive-green bird landed on the feeder and pulled seed messily into its blunt, thick beak, flew into the hawthorn, and then flew back to the feeder. Definitely a greenfinch. I’ve not seen it since, but it looked healthy, and I took that pure jolt of happiness into the rest of my day.

Love of nature

That is the feeling that lies at the heart of my Love Letters on the River, and of my life, I think. The awe-filled, sweet, vast love for the creatures that live around me. Look at that bee that’s just landed on your wrist. Look at it. Have you filled bowls and saucers in your garden for all the wild and non-human life that might be thirsty and in need this summer? Listen to those swifts charging and screaming overhead. Remember that sound, because in a decade or two you may never hear it again. Your grandchildren may never know what a swift is.

To (possibly mis)quote the philosopher John Gray, from his book Straw Dogs: “The humanist sense of a gulf between ourselves and other animals is an aberration. It is the animist feeling of belonging with the rest of nature that is normal.”

Yes. Absolutely, that.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.