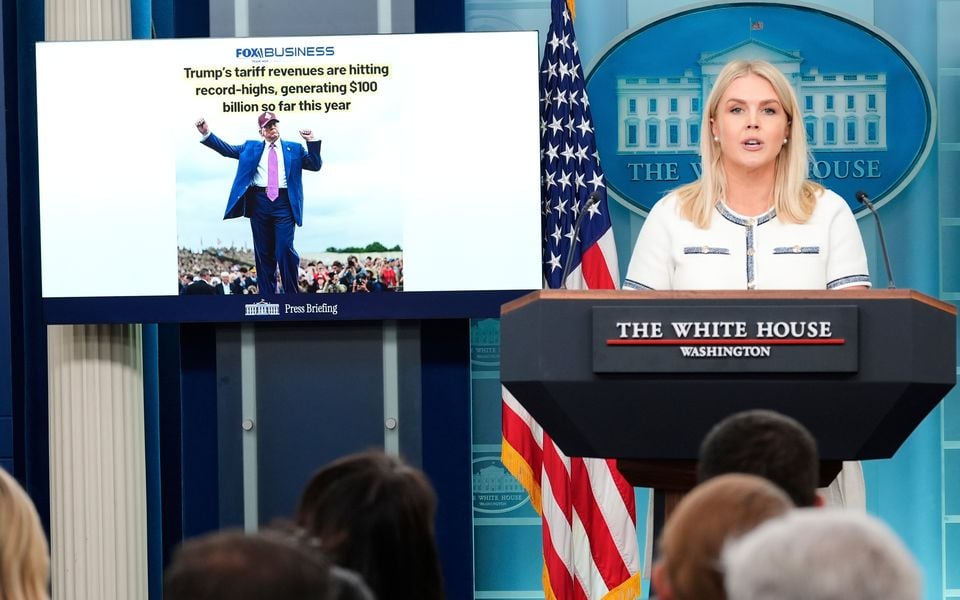

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt speaks with reporters in the James Brady Press Briefing Room at the White House, on July 17, 2025, in Washington. [Alex Brandon/AP]

The problem with trying to negotiate with the Trump administration is that no one knows whether you have got a deal until the president has personally signed off on it. This uncertainty extends to Trump’s own advisers, one European official with first-hand experience of negotiating with this US government told me last week. You might think you are making progress with your American counterparts, but the Art of the Deal is a 24-hour a day TV Show. You never know what new plot lines may be required to keep the audience entertained.

That is how the European Commission found itself blindsided last weekend by Trump’s threat to impose a 30 percent tariff on all imports from the European Union. It came just days after Brussels officials had expressed optimism that a deal was close. The EU had been reluctantly ready to accept a 10 percent baseline tariff similar to that agreed by the UK and was focusing on trying to secure exemptions from current and planned sectoral tariffs on cars, steel, aluminium and pharmaceuticals. It is safe to say that even this bad deal is now off the table.

On the other hand, failure to strike a deal could have disastrous economic consequences, if that led to Trump following through on his threats., Markus Sefkovic, the EU trade commissioner, is clearly right when he says that a 30 percent tariff would effectively halt transatlantic trade and be devastating to the European and global economy – even before Brussels retaliated. After all, the EU and US between them accounting for 43 percent of global GDP and 30 percent of global trade. That suggests the threat is a negotiating ploy. But what concessions would satisfy Trump? If that wasn’t clear before, it’s even less clear now.

Nor can Brussels count on the markets to come to its aid. When Trump announced his “Liberation Day” tariffs on April 2, the market reaction was so severe that he backed down after a week. Now he says he will hit the EU with an even higher tariff than the 20 percent threatened then, yet the markets have barely blinked. Indeed, if one includes all the latest tariff “deals” due to take effect from the beginning of August, including 50 percent on Brazil, 30 percent on Mexico, 35 percent on Canada, and 25 percent on Japan and South Korea, then America’s average tariff rate will rise back above 20 percent, up from around 13 percent now and a little over 2 percent at the start of the year. This is not far off the level that rattled investors in April.

Of course, the market’s complacency partly reflects the TACO trade – the expectation that Trump Always Chickens Out. Indeed, the only thing that actually changed last weekend was that the president pushed back the deadline for the EU to reach a deal by three weeks. Meanwhile, investors are becoming increasingly optimistic about the long-term outlook for the US economy and corporate earnings, buoyed by the boost from Trump’s tax-cutting Big Beautiful Budget Bill and the transformative potential of AI. Despite warnings from economists that the higher tariffs will lead to higher inflation and lower growth, this has yet to show up in the data.

That makes this situation particularly dangerous. The EU ultimately faces no good options. It can settle for a more damaging deal than anything it could have contemplated even a few weeks ago. Or it can hold out for an acceptable deal – and follow through on its own threats to retaliate if it can’t get one in the hope that the economic shock might shake the markets out of their complacency. In weighing its options, the EU will also be aware of the danger that Trump might weaponise other aspects of the relationship, not least US security guarantees.

Yet the EU may have little choice but to retaliate if Trump continues to make unacceptable demands. A bad deal that saddled EU exports with tariffs of 20 percent or more would only undermine the EU’s own legitimacy, particularly relative to Brexit Britain, which faces tariffs of only 10 percent. Indeed, undermining the legitimacy of the EU may be part of Trump’s agenda. Besides, the risk that Trump might withdraw security guarantees may have receded following last month’s NATO summit, and Trump’s apparent pivot on providing arms to Ukraine.

That said, who knows what Trump might decide to do next? The answer is not even Trump.

Simon Nixon is an independent commentator and the publisher of the Wealth of Nations newsletter on Substack.